Constitution of the State of California, 1849

Article I

Sec. 1.

All

men are by nature free and independent, and have certain unalienable

rights, among which are those of enjoying and defending life and

liberty: acquiring, possessing and protecting property: and pursuing and obtaining safety and happiness.

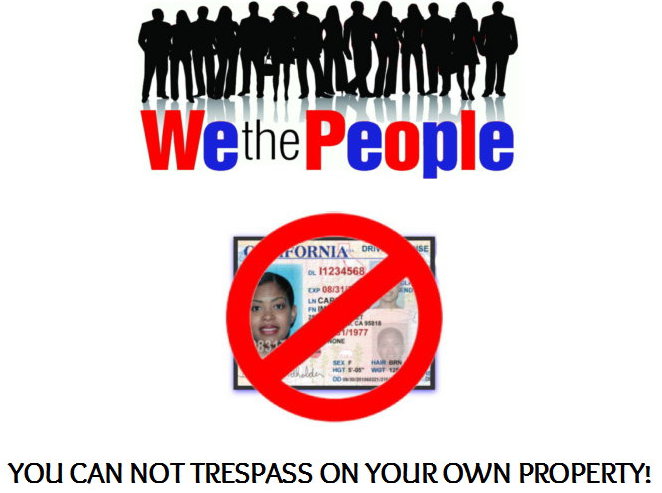

This is PROPERTY:

The following is what is not taught to anyone forced to go to skool for

the 12 years that mom & dad are forced to pay for. Mom

& dad deserve a refund. Everybody knows what one of these types of things (property) are:

But while being forced to go to skool for 12 years

no one was ever taught the history about the development of the rules

that apply to the use of one of those things. But everybody

PRESUMES to know what the rules are. That's a really big

mistake.

The following information is

located in Volume 5 of American Jurisprudence. American

Jurisprudence is a law encyclopedia. The volumes comprising the

series contains information about pretty much every topic you can think

of.

Before there were machines like

that VW, there were no rules concerning their regulation because such

machines didn't exist. Once a certain number of those

things were invented, law makers developed rules applicable to their

use. Checking the historical record of those machines and

the rules applicable to them is an advantage when it comes to licensing

and getting stopped by a law enforcement employee for violating a rule

in the Vehicle Code.

5 Am. Jur.

Copyright 1936

ATTACHMENT

to

AUTOMOBILES

~~~~~~~~~~~~

AUTOMOBILES

§3. Generally.

– The term “automobile” has its derivation in the Greek “autos,”

meaning “self,” and the Latin “mobiles,” meaning “movable.”

“automobile,” therefore, means “self – moving.” It may be

defined as a wheeled vehicle propelled by steam, electricity, or

gasoline, and used on highways and streets for the transportation of

persons or merchandise. The courts, without making clear

distinctions, have generally use the terms “automobile,” “motor

vehicle,” “motor car,” – and, in the earlier cases “horseless

carriage,” – as synonyms. Questions frequently arose as to

whether statutes regulating the use of various classes of vehicles, and

not directly referring to automobiles, were brought enough to apply to

such machines, which, in numerous instances, were unknown at the time

of the passage of the law. The better view seems to be that an

automobile is to be classed as a vehicle, and may properly be

considered as being a vehicle for hire, under the terms of ordinances

prohibiting the standing of such vehicle in the streets elsewhere than

at public hack stands. The term “motor vehicle” is not,

however, comprehensive enough to include a boy’s sled.

§4. Automobile as “Carriage” or “Wagon.”

– Whether or not an automobile falls within the meaning of the

word “carriage” as used in a statute depends somewhat upon the nature

of the statute. In a penal statute, in a proper case, it

may not be so included, while in a statute which should receive a

liberal construction, it will be. An automobile is a

“carriage” within the broad meaning of that term. Thus, a

motorcar is a “carriage” within the meaning of a grant of a lot which

is part of a tract purchased for a public park, conveyed to the

purchasers, “together with the right of carriage, horse, and foot way

through the park when laid out.” But it is been held not to

be a carriage, within the meaning of a statute requiring towns and

cities to keep their highways “reasonably safe and convenient for

travelers with their horses, teams, and carriages.”

Generally speaking, an automobile is not a wagon, although it has been

held that it is a wagon within the meaning of ordinances prohibiting

the presence of “advertising trucks, vans, or wagons” upon certain

streets.

§8. Public Conveyances.

– Taxicabs vehicle propelled by electric or gas power, held for

public hire. It is sometimes noted in the definitions of

the charges or upon a time or distance basis, and also that the vehicle

is held for public hire at designated places subject to municipal

control.

A jitney as a vehicle of motor

class, the charges of which are much lower than that of a taxicab, the

stipulated fair usually being five or ten cents, directly in

competition with street cars.

Fn. 11 - Taxicabs are the modern development of the old hackney coach. Park Hotel Co. v. Kechum, 184 Wis. 182

Let's have a look at how the

Legislature classified "things", "stuff", "possessions", or "property":

WEST'S CALIFORNIA CODES

1990

California Commercial Code §9109

Classification of Goods: "Consumer Goods"; "Equipment"; "Farm Products"; "Inventory"

Goods are

(1) "Consumer goods" if they are used or bought for use primarily for personal, family or household purposes;

(2) "Equipment" if they are

used or bought for the use primarily in business (including farming or

a profession) or by a debtor who is a nonprofit organization or a

government subdivision or agency or if the goods are not included in

the definitions of inventory, farm products, or consumer goods.

California Code Comment

By John A. Bohn and Charles J. Williams

Prior California Law

1. The classification of goods in

this section is new statutory law. The significance of this

classification is described in Official Comment 1.

Although goods cannot belong to more than one category at any time,

they may change their classification depending upon who holds them and

for what reason. Each classification is mutually exclusive but the four

classifications described are intended to includeall goods.

Official Comment 2.

CALIFORNIA CIVIL CODE

1791. As used in this chapter:

(a) "Consumer

goods" means any new product or part thereof that is used, bought, or

leased for use primarily for personal, family, or household purposes,

except for clothing and consumables. "Consumer goods" shall include new

and used assistive devices sold at retail.

CALIFORNIA CODE OF CIVIL PROCEDURE

481.100.

"Equipment" means tangible personal property in the possession of the

defendant and used or bought for use primarily in the defendant's

trade, business, or profession if it is not included in the definitions

of inventory or farm products.

So according to the Legislature, which is the law

making branch of government, even though those Volkswagan vans are

similar in design, HOW THEY'RE USED is very different. One USE is

for commercial or business purposes, or for HIRE, and the other

isn't. The other is arguably USED for personal pleasure,

household and nonCOMMERCIAL/BUSINESS purposes, hence it properly

belongs in the CONSUMER GOODS category.

Now let's check what more than a few courts have held concerning "CONSUMER GOODS":

“Automobile owned by individual not in business is ‘consumer goods’”.

In re Rave, 7 UCC rep. Serv 258.

“An automobile purchased for personal and family use was ‘consumer goods’”.

Bank of Boston v. Jones, 4 UCC Rep. Serv. 1021, 236 A.2d. 484

“The use of an automobile by its owner for purposes of traveling

to and from his work is a personal, as opposed to a business use as

that term is defined in the California Commercial Code 9109(1), and the

automobile will be classified as ‘consumer goods’ rather than

equipment. The phraseology of §9102(2) defining goods used or

bought for use primarily in business seems to contemplate a distinction

between the collateral automobile ‘in business’ and the mere use of the

collateral automobile for some commercial, economic or income producing

purpose by one not engaged in ‘business’”.

In re Barnes, 11 UCC rep. Serv. 697 (1972)

“So long as one uses his private property for private

purposes and does not devote it to the public use, the public has no

interest in it and no voice in its control.

Associated Pipe v. Railroad Commission (1920) 176 Cal. 518.

“Under the UCC §9-109 there is a real distinction between goods

purchased for personal use and those purchase for business use.

The two are mutually exclusive and the principal use to which the

property is put should be considered as determinitive”.

James Talcott, Inc. v. Gee, 5 UCC rep. Serv. 1028, 266 Cal.App.2d. 384, 72 Cal.Reptr. (1968).

“The use to which an item is put rather than its physical

characteristics determine whether it should be classified as ‘consumer

goods’ under UCC §9-109(1) or ‘equipment’ under UCC §9-109(2)”.

Grimes v. Massey Ferguson, Inc., 23 UCC Rep. Serv. 655, 355 So. 2d. 338 (Ala., 1978)

“The classification of goods in UCC §9-109 are mutually exclusive”.

McFadden v. Mercantile-Safe Deposit & Trust Co., 8 UCC Rep. Serv. 766, 260 Md. 601, 273, A.2d. 198 (1971)

“The term ‘household goods’..includes everything about the house

that is usually held and enjoyed therewith and that tends to the

comfort and accommodation of the household”.

Lawwill v. Lawwill,

515 P.2d. 900, 903, 21 Ariz.App.75 , 19A Words and Phrases - Permanent

Edition (West) pocket part 94.

“Automobile purchased for the purpose of transporting buyer to and

from his place of employment was ‘consumer goods’ as defined in UCC

§9-109".

Mallicoat v. Volunteer Finance & Loan Corp., 3 UCC Rep. Serv. 1035, 415 S.W.2d. 347 (Tenn.App., 1966)

“A carriage is peculiarly a family or household article. It

contributes in a large degree to the health, convenience, comfort and

welfare of the householder or of the family”.

Arthur v. Morgan., 113 U.S. 495, 500, 5 S.Ct. 241, 243 (S.D.Ny 1884)

Courts have no right, no power, to extend statute by construction,

so as to dispense with any conditions legislature has seen fit to

impose. Gassner v. Patterson, (1863) 23 C. 299; likewise, the

Courts must take the statute as they find it. It is their

duty to construe it as it stands enacted. Callahan v. San

Francisco, (1945) 68 CA2d. 286, 156 P.2d. 479; Santa Clara County Dist.

Atty.

Investigators Asso. v. Santa Clara County, (1975) 51 Cal.App.3d. 255, 124 Cal.Rptr. 115.

Courts are not at liberty to extend application of law to subjects not included within it.

Spreckles v. Graham (1924) 194 C. 516

CALIFORNIA VEHICLE CODE

Commercial

Vehicle

260. (a) A "commercial

vehicle" is a motor vehicle of a type required to be registered under this

code used or maintained for the transportation of persons for hire,

compensation, or profit or designed, used, or maintained primarily for the

transportation of property.

(b) Passenger vehicles and

house cars that are not used for the transportation of persons for hire,

compensation, or profit are not commercial vehicles. This subdivision shall

not apply to Chapter 4 (commencing with Section 6700) of Division 3.

Arguably, any machine used as defined by (b) is not

required to be registered. And according to the California

Supreme Court in the Spreckles v. Graham decision, the courts can not extend Vehicle Code sec. 260(a) to those machines NOT FOR HIRE ie:

CONCLISION:

HOW THE MACHINE/THING IS USED DETERMINES WHAT CATEGORY OR CLASS OF

PROPERTY IT BELONGS IN AND NO COURT HAS THE AUTHORITY TO RECLASSIFY AN

ITEM OF CONSUMER GOODS AS EQUIPMENT.

AM.JUR. CONTINUED

AM.JUR. CONTINUED

§9. Streets and Highways.

– The problem frequently arises as to whether or not the term “Highway”

as used in the statutory provision relating to vehicle traffic includes

“street.” This problem cannot be regarded as entirely

settled. The legislative intent, as indicated by the

wording of the various statutes, determines the scope of the term.

Let's take a look at what a few courts have held

about the use of the streets and highways:

The state has the authority to regulate the use of public highways for business purposes.

Morel v. Railroad Commission of California (1938) 11 Cal.2d 488

“Whatever natural right the citizen may have to traverse the streets of

his city with a motor vehicle for the conveyance of his family or his

friends, no inherent right to exist to devote his vehicle to the public

use of carrying passengers for hire, and to appropriate to himself the

use of all streets for the purpose of profit. Beyond

question, the city could vacate one or more of the streets over which

he might desire to operate. It cannot only require him to

pay a license tax, but it may also regulate the manner of his carrying

on his enterprise. Why may it not classify motor vehicles

by themselves, and refused to permit them to crowd congested portions

of the business streets where patrons of another class of vehicles –

streetcars – must the light and take passage? Suppose,

indeed, a company or corporation owning motor vehicles had the

facilities and the desire to occupy all the streets to the utter

destruction of the streetcar business. Would the city have

nothing to say? Is a municipality mere automation, helpless

in the presence of crowding and conflicting enterprises and scrambles

for business which involve the comfort, the convenience, and the safety

of the traveling public? Not so.”

Dresser v. Wichita, 96 Kan. 820 (1915)

"'The right of a citizen to travel upon the highway and transport his

property thereon in the ordinary course of life and business differs

radically and obviously from that of one who makes the highway his

place of business and uses it for private gain,... The former is the

usual and ordinary right of a citizen, a right common to all; while the

latter is special, unusual and extraordinary.

Frost v. Railroad Commission (1925) 197 Cal. 230

"…the right of the citizen to drive on a public street with freedom

from police interference, unless he is engaged in suspicious conduct

associated in some manner with criminality, is a fundamental

constitutional right..."

People v. Horton (1971) 14 Cal.App.3d 930

"It is settled that the streets of a city belong to the people of a

state and the use thereof is aninalienable right of every citizen of

the state."

Whyte v. City of Sacramento (1924) 65 Cal. App. 534

Escobedo v. State Dept. of Motor Vehicles (1950) 35 Cal.2d 870

The right of a citizen to teavel upon the public highways and to

transport his property thereon, either by horse-deawn carriage or wagon

or automobile, is not a mere privilege which a city may permit or

prohibit at will, but a common right, which he has under his right to

life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

Thompson v. Smith, 155 Va. 367, Supreme Court of Virginia, (1930)

In the matter of Ex parte Dickey,

76 W.Va. 567 (1940), the West Virginia Supreme Court held, wherein it

appeared that a city passed an ordinance regulating the use of jitney’s

on the streets, the ordinance to be valid, saying: “the right of a

citizen to travel upon the highway and transport his property thereon,

in the ordinary course of life and business, differs radically and

obviously from that of one who makes the highway his place of business

and uses it for private gain, in the running of a stagecoach or

omnibus. The former is the usual and ordinary right of a

citizen, a common right, a right common to all, while the latter is

special, unusual but, as to the latter, its power is broader, – the

right may be wholly denied, or it may be permitted to some and denied

others, because of its extraordinary nature. This

distinction, elementary and fundamental and character, is recognized by

all the authorities.”

Clearly

the courts have distinguished between the COMMERCAIL and NONCOMMERCIAL

use of the streets and highways, one being privileged and the other an

unalienable right. Regarding the Morel

citation, what evidence would the State issue to distinguish COMMERCIAL

from NONCOMMERCIAL use of the streets and highways so law enforcement

employees didn't inadvertently stop someone who's not engaged in

COMMERCE/BUSINESS?

AM.JUR. CONTINUED

AM.JUR. CONTINUED

C. STATUS

§10. Generally; Right to Use Highways.

– Obviously, the use of the highways by automobiles is

lawful. The owners and operators thereof have the right to

use the highways of the state on an equal footing with the drivers of

other vehicles, unless the size and character of the vehicle is

restricted by the legislature. The fact that vehicles are

heavier than those customarily used does not give the court, or anyone

else, an action for such use. A county can neither restrain

an owner from using the public roads and bridges because of the size of

his vehicles, nor collect damages for their reasonable use.

But this equality or right imposes the reciprocal duty of managing

one’s vehicle, whatever its character, with care and caution to avoid

causing injury to others with equal right.

In early cases it was declared

that where highways had not been restricted by dedication to some

particular motive use, they were open to all suitable methods of

transportation, and a new means of making the way useful cannot be

excluded merely because it’s introduction might tend to the

inconvenience, or even to the injury, of those who continue to use road

after the same manner as formerly; and although travel upon the public

roads had, until a comparatively recent date, chiefly been by means of

horses, persons making use of these animals for purposes of travel had

no prescriptive rights or privileges superior to those who had recourse

to other methods of locomotion upon the public

thoroughfares. The automobile was considered in ordinary

vehicle for pleasure or business, furnishing a convenient and useful

mode of travel and transportation not necessarily inconsistent with the

proper use of the highways by others, and while it was generally

recognized that motor vehicles had introduced a new element of danger

to travelers on the highway, necessarily exacting a degree of care

commensurate with their use, yet such vehicles had rights upon the

public roads and streets equal to those of horses, carriages, and other

vehicles.

§11. Automobile as Dangerous Instrumentality.

– Although there is some authority to the contrary, it is a principle

of law well established by the great weight of authority that an

automobile – at least an automobile and proper repair – or motorcycle

is not inherently a dangerous agency so as to render the owner or

operator thereof liable as an insurer for injuries caused

thereby. Liability, if any, must rest upon

negligence. The rules requiring extraordinary care of

dangerous instrumentality’s do not apply to automobiles. In

other words, automobiles are not to be regarded in the same category

with locomotives, ferocious animals, dynamite, and other dangerous

contrivances and agencies.

In accordance with these

principles, and owner of an automobile is not responsible for injuries

which may be sustained by strangers from its careless and wrongful use

while in the possession of another who is using it without his

consent. Nor can he be held responsible for the acts of his

servant in operating the machine without authority, although he knew

that the servant was unskillful and careless. An automobile

in good condition is not a dangerous instrument that one letting it for

hire must test the competency and skill of a customer before intrusting

him with it, under penalty of liability for injuries done by the

hirer’s negligence.

§12. – Apparent Limitations Upon Dangerous Agency Rule.

– Although, as shown above, it is a well established principle that an

automobile is not inherently a dangerous machine, this principle must

be considered in the light of other principles affecting

it. For example, it is the general rule in the law of

negligence at the care to be exercised in the use of any

instrumentality is proportionate to the possibilities of injury from

its careless use; and in a number of cases the courts have referred to

the automobile as a dangerous instrumentality in the sense that a high

degree of care must be exercised by the person operating

it. This “high degree” of care may be regarded as by

ordinary care under the circumstances, the fact that the

instrumentality used is an automobile constituting one of the

circumstances. It is been asserted that the automobile is a

dangerous instrumentality “when driven upon the highways in the

careless and negligent manner,” and that an automobile is a machine of

such “dangerous potentialities” that it is negligence for the owner to

intrusted to an incompetent or inexperienced person.

§13. Automobile as a Nuisance.

– Since he use the highways by automobiles is lawful, the motor vehicle

cannot be regarded as a nuisance per se. There is a

difference of opinion upon the question whether an automobile is an

attractive nuisance. The general view is that it is not,

although under certain circumstances the automobile has been held to be

such a nuisance. Where the owner finds an infant of tender

years in his car he is not absolving of liability by driving it from

the car, but is required to exercise reasonable care to avoid injury to

the child thereafter.

§14. Automobile as Tool or Implement of Trade.

– The question occasionally arises as to whether or not an automobile

is a “tool,” “implement,” “instrument,” “utensil,” or “apparatus”

within the meaning of the debtors exemption laws.

Obviously, the determination of this question depends to a large extent

upon the wording of the statute and upon the specific factual situation

involved. An automobile has been held not to be a tool or

implement of trade within the meaning of the exemption

laws. A truck in an automobile owned by a farmer and used

by them for general farm purposes, including the marketing of farm

produce, have been held not to be farm “tools” or “instruments” within

the meaning of an exemption statute but are to be classed as

“vehicles,” where the statute contains the further classification of

“the wagon or other vehicle, etc.,” of a farmer as being

exempt. It is also been held that an automobile of a

licensed professional chauffeur is not within a statute exempting “the

tools and necessary implements to the extent of $200, used by the

execution debtor in the practice of his trade or profession.”

II. PUBLIC REGULATION AND CONTROL

A. POWER OF REGULATION

§15. Federal Government.

– The power of the federal government to regulate interstate commerce

gives control over motor vehicles engaged in business between one state

and another in the same degree as such control exists as to any other

class of vehicles engaged in the same occupation. However,

as to what constitutes “commerce” of an interstate character, the

United States Supreme Court has given a definition which fails to

include pleasure vehicles engaged in interstate travel.

Concerning police regulations within state limits, the United States

government, under ordinary circumstances, has no constitutional

authority. The power to regulate commerce among the states

has always been understood as limited by its terms and as a virtual

denial of any power to interfere with the internal trade and business

of the several states.

§23. Class Legislation. - A

licensing ordinance applying only to those who use their automobiles

for merely private business or pleasure has, been considered invalid.

§50. Limitations upon Use of Streets by Motor Vehicles for Hire. - Under

the well-settled rule that a municipality having the power to regulate

the use of its streets may pass any reasonable ordinance within its

delegated powers governing automobile traffic on the streets, it has

been generally held that a municipality has a right to pass an

ordinance prohibiting or limiting the use of certain streets by motor

vehicles operated for hire. Thus, an ordinance prohibiting

chimneys from using public streets, unless they paid additional license

tax, was held reasonable and valid, as was an ordinance prohibiting

jitney buses from operating within certain designated

zones. Likewise, where a motor bus line running between two

cities was prohibited by virtue of an ordinance in one of the cities,

from using certain streets when running through that city, it was held

that the ordinance was reasonable because it tended to relieve the

congested traffic conditions of the city. It has, however,

been held that an ordinance for bidding duly licensed cabdrivers to

operate their vehicles on the principal streets of the city between

certain points, except to discharge and take up passengers on prior

calls, in which case the vehicle must enter and leave the street at the

point nearest the place where the passenger is to be taken or

discharge, is an unconstitutional interference with the rights of such

drivers.

Note that section 50 has to do with

COMMERCE/BUSINESS. Note the terms used that apply to

COMMERCE/BUSINESS:

- Traffic

- Motor Vehicle

- Hire

- Passenger

- licensed cab driver

What

class license is issued to a cab driver? If you don't know

then simply call your local cab company and ask what class license is

required to be hired as a cab driver. In California the

class is Class C, which is the the class license issued to nearly

everyone who wants to use a car, truck, or van.

Predicated

on the foregoing information, we've been mislead. Everyone

who's got a Class C license is PERMITTED to use the streets and

highways for COMMERCIAL/BUSINESS = TRAFFIC purposes, however that same

license is NOT REQUIRED to travel by car, truck or van for

NONCOMMERCIAL household purposes or for the common purpose of

NONCOMMERCIAL travel. The Class C license PERMITS the use

of a "motor vehicle" to deliver/carrry/haul passengers or merchandise

from Point A to Point B for compensation or hire.

Educational slide shows are available for viewing and downloading here: http://thelawsalon.net/mytube.html

Educational slide shows are available for viewing and downloading here: http://thelawsalon.net/mytube.html Research and Study Materials available here: http://thelawsalon.net/research.html

Research and Study Materials available here: http://thelawsalon.net/research.html