PEACE OFFICER (police, Highway Patrol, Sheriff deputies) EMPLOYEES HAVE NO MANDATORY DUTY TO PROTECT YOU

We

thus require citizens to apprise themselves not only of statutory

language but also of legislative history, subsequent judicial

construction, and underlying legislative purposes (See generally

Amsterdam, The Void-For-Vagueness Doctrine in the Supreme Court (1960)

109 U. Pa. L.Rev. 67.)

Walker v. Superior Court (1988) 47 Cal.3d 112

People v. Grubb (1965) 63 Cal.2d 614

CALIFORNIA CIVIL CODE

1708.

Every person is bound, without contract, to abstain from injuring the

person or property of another, or infringing upon any of his or her

rights.

"Common as the event may be, it is a serious thing to arrest a citizen,

and it is a more serious thing to search his person; and he who

accomplishes it, must do so in conformity to the law of the

land. There are two reasons for this; one to avoid

bloodshed, and the other to preserve the liberty of the

citizen. Obedience to the law is the bond of society, and

the officers set to enforce the law are not exempt from its mandates.".

Town of Blacksburg v. Bean 104 S.C. 146. 88 S.E. 441 (1916)

Allen v. State, 197 N.W. 808, 810-11 (Wis 1924)

Even if the officer is not expected to know the law of all 50 states,

surely he is expected to know the California Vehicle Code...

CLEMENT v. J & E SERVICE INC., No. 05-56692, March 11, 2008, UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT

Even if the officer is not expected to know the law of all 50 states,

surely he is expected to know the California Vehicle Code,...

THE PEOPLE v. JESUS SANTOS SANCHEZ REYES (2011) 196 Cal.App.4th 856

...'[a]n officer is under no duty to make an unlawful arrest.'

[Citation.] It goes without saying, of course, that neither is it

the duty of officers to taunt or beat persons arrested."

People v. White (1980) 101 Cal.App.3d 161

...a peace officer is under no duty to make an unlawful arrest.

[5] Moreover, it is a public offense for a peace officer to use

unreasonable and excessive force in effecting an arrest (Boyes v.

Evans, 14 Cal.App.2d 472 ...). Therefore, a person who uses

reasonable force to protect himself or others against the use of

unreasonable excessive force in making an arrest is not guilty of any

crime (Pen. Code, §§ 692, 694).

People v. Cuevas (1971), 16 Cal.App.3d 245

We are of the opinion that the law does not permit the citizen to

consent to an unlawful restraint nor such claim to be made upon the

part of the defendants. It is so held to assault and battery, Cooley on

Torts (2d Ed.) 188, which is part of the charge in the complaint, and

we think the principle equally applicable to restraint, which includes

an assault.

Meints v. Huntington, 276 Fed. 245, 19 A.L.R. 664

Contrary to popular belief, the

police have no duty to protect you. They "may", the have

discretion, but they have no mandatory duty to protect you.

You will find NO LAW that imposes an obligation on police employees to

protect anyone.

Someone's been lyin! Someone's beliefs are FALSE!

Police, Highway Patrol, and Sheriff

deputies ARE NOT REQUIRED to protect individual citizens from other

citizens, contrary to popular belief. In fact most

people believe police

HAVE TO arrest when they witness crime. That is completely

false. There is NO MANDATORY DUTY imposed on police

employees to protect or arrest anyone. Where is it

written that applicants for the job of cop is REQUIRED to take a bullet

for anyone as a condition of qualifying for employment?

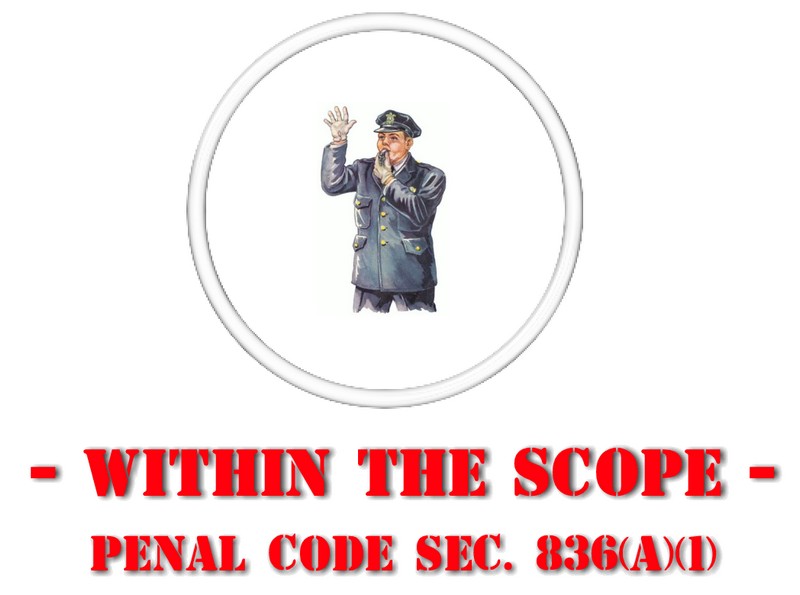

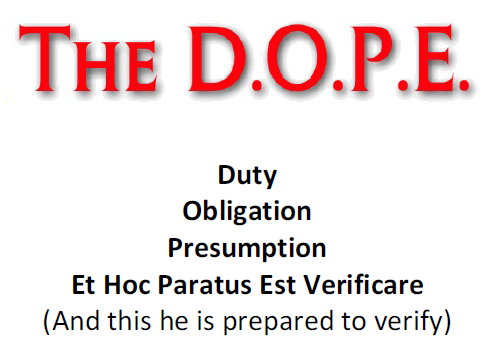

This is the ARREST authority provided by the California Legislature:

CALIFORNIA PENAL CODE

836. (a)

A peace officer may arrest a person in obedience to a warrant, or,

pursuant to the authority granted to him or her by Chapter 4.5

(commencing with Section 830) of Title 3 of Part 2, without a warrant,

may arrest a person whenever any of the following circumstances occur:

(1) The officer has probable cause to believe that the person to be arrested has committed a public offense in the officer's prese

CALIFORNIA GOVERNMENT CODE

14. "Shall" is mandatory and "may" is permissive.

The term "shall" is not included in

the section that applies to arrests. If you happen to be

arrested by a police officer then you might ask them the question

during your trial whether they were required to arrest you or

not. There's only one correct answer and it's located in

the very book police officers enforce that identify crimes, the Penal

Code.

CALIFORNIA GOVERNMENT CODE

820. (a) Except as otherwise provided by statute (including Section 820.2), a public employee is liable for injury caused by his act or omission to the same extent as a private person.

(b) The

liability of a public employee established by this part (commencing

with Section 814) is subject to any defenses that would be available to

the public employee if he were a private person.

820.2. Except as

otherwise provided by statute, a public employee is not liable for an

injury resulting from his act or omission where the act or omission was

the result of the exercise of the discretion* vested in him, whether or not such discretion be abused.

*

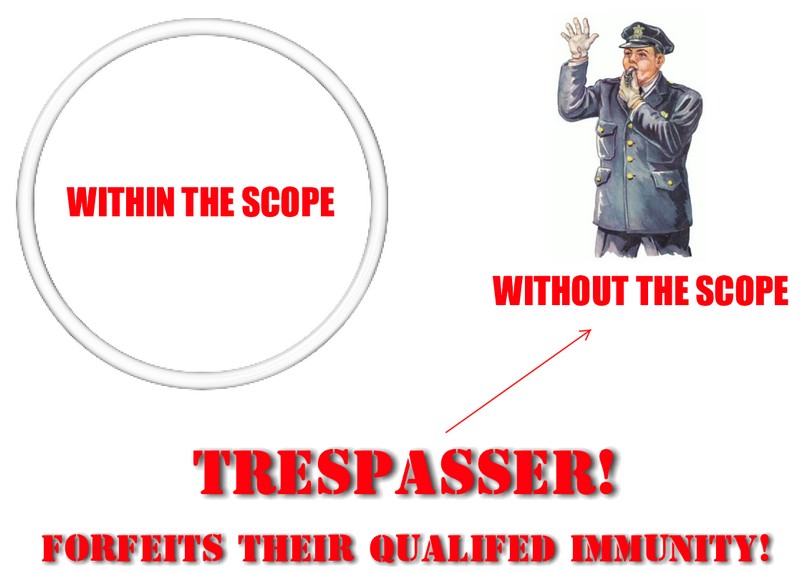

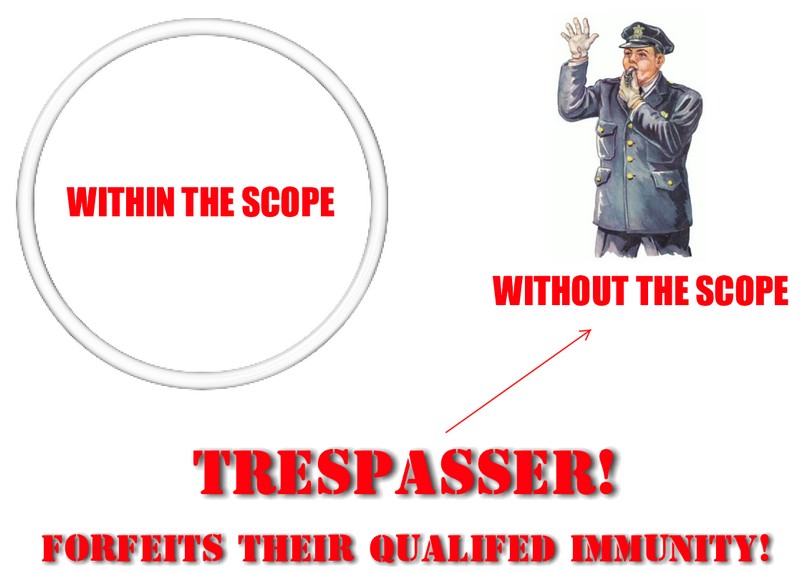

DISCRETION is the BARE ASS MINIMUM authorization. What’s

beneficial or useful, in my opinion, is the fact, the undeniable fact,

that the officer employee is not required or mandated to

act. They do not have to arrest anyone without a

warrant. The Legislature has not imposed a mandatory

obligation enjoining law enforcement officers to arrest without a

warrant when they observe a crime committed in their presence.

The following court decisions prove

that peace officer employees (police, Highway Patrol, Sheriff deputies)

DO NOT HAVE ANY DUTY TO PROTECT YOU:

DUTY OF CARE - SPECIAL RELATIONSHIP - TRAFFIC ENFORCEMENT STOP - MISFEASANCE - NONFEASANCE

1. Lugtu v. California Highway Patrol (2001) 26 Cal. 4th 703

2. Lugtu v. California Highway Patrol (2000) 79 Cal. App. 4th 35

3. People v. Espino (2016) 247 Cal. App. 4th 746

4. DESHANEY v. WINNEBAGO CTY. SOC. SERVS. DEPT., 489 U.S. 189 (1989)

5. Balistreri v. Pacifica Police Department, 901 F.2d 696 (9th Cir.) (1988)

6. SCREWS v. U.S., 325 U.S. 91 (1945)

7. Eyrle S.

Hilton, IV, v. City of Wheeling, et al., (2000) No. 99-3727, In the

United States Court of Appeals For the Seventh Circuit

8. Whitton v. State of California (1979) 98 Cal. App. 3d 235

9. Rowland v. Christian (1968) 69 Cal. 2d 108

10. Adams v. City of Fremont (1998) 68 Cal. App. 4th 243

11. Grudt v. L.A. (1970) 2 Cal. 3d 575

12. Reed v. San Diego (1947) 77 Cal. App. 2d 860

13. Kaisner v. Kolb, 543 So. 2d 732 (1989), Supreme Court of Florida.

14. Jackson v.

Ryder Truck Rental, Inc. (1993) 16 Cal. App. 4th 1830

15. McCorkle v. City of Los Angeles (1969) 70 Cal. 2d 252

16. Wallace v. City of Los Angeles (1993) 12 Cal. App. 4th 1385

17. Mann v. State of California (1977) 70 Cal. App. 3d 773

18. CARROLL v. U.S., 267 U.S. 132 (1925)

19. HENRY v. UNITED STATES, 361 U.S. 98 (1959)

20. UNITED STATES

OF AMERICA v. DONALD KEITH BURTON (2003) No. 02-60428, IN THE UNITED

STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

The first three

cases of 119 returned by Lexis, are the only cases in California that

contain the term “traffic enforcement stop”.

Cases 4 - 7

provide the proof that there is no constitutional requirement for State

or local government to provide police service. They also

acknowledge that there is no mandatory duty for peace officers to

provide protection to individual members of the citizenry.

California Penal

Code §836(a)(1) is proof peace officers have no mandatory duty to arrest

anyone and that the duty to arrest is discretionary.

California Penal Code §19.6 prohibits imprisonment for

infractions. A “traffic stop” is imprisonment and has been

identified by the Legislature as an arrest, the procedures for which

are located in the Vehicle Code beginning at §40300.

...traffic stops are technically “arrests”...

"Investigative Detentions", Spring 2010 POINT OF VIEW, ALAMEDA COUNTY DISTRICT ATTORNEY’S OFFICE. p. 1

A traffic arrest occurs when an officer stops a vehicle after seeing the driver commit an

infraction. ...the purpose of the stop is to enforce the law, not conduct an investigation.

“Arrests”, Spring 2009, POINT OF VIEW, ALAMEDA COUNTY DISTRICT ATTORNEY’S OFFICE, p. 1

AN ARREST FOR NONCRIMINAL CONDUCT IS A CRIME REGARDLESS OF WHO MAKES THE ARREST!

Lugtu v. California Highway Patrol

Supreme Court of California

August 16, 2001, Decided

No. S088116.

26 Cal. 4th 703

CECELIO LUGTU et al., Plaintiffs and Appellants, v. CALIFORNIA HIGHWAY PATROL et al., Defendants and Respondents.

Prior History:

Superior Court of San Diego County.

Super. Ct. No. N76651. David B. Moon, Jr., Judge. Court of Appeal of

California, Fourth Appellate District, Division One. D032518.

CALIFORNIA OFFICIAL REPORTS HEADNOTES

Classified to California Digest of Official Reports

CA(1) (1) Negligence § 9 — Elements of Actionable Negligence — Duty of Care — Statement of Rules.

– Under general negligence

principles and Civ. Code, § 1714, a person ordinarily is obligated to

exercise due care in his or her own actions so as not to create an

unreasonable risk of injury to others, and this legal duty generally is

owed to the class of persons who it is reasonably foreseeable may be

injured as the result of the actor's conduct. Moreover, one's general

duty of care includes the duty not to place another person in a

situation in which the general duty of care includes the duty not to

place another person in a situation in which the other person is

exposed to an unreasonable risk of harm through the reasonably

foreseeable conduct (including the reasonably foreseeable negligent

conduct) of a third person.

CA(2a) (2a) CA(2b) (2b) CA(2c) (2c)

CA(2d) (2d) Negligence § 92 — Actions— Trial and Judgment — Questions

of Law and Fact — Duty of Care — Duty of Officer Who Pulls Over Vehicle

on Highway: Law Enforcement Officers § 17 — Police — Rights and Duties

— Officer's Duty of Care When Directing Vehicle to Side of Road.

– In an action against the

California Highway Patrol (CHP) and a CHP officer arising from a

traffic accident in which plaintiffs, occupants of a car that had been

pulled over into a highway median strip by the officer, were struck by

a truck that drifted out of its lane, the trial court's grant of

summary judgment in favor of defendants could not be sustained on the

ground that the officer owed plaintiffs no legal duty. A law

enforcement officer has a duty to exercise reasonable care for the

safety of persons whom the officer stops, and this duty includes the

obligation not to expose such persons to an unreasonable risk of injury

by third parties. Further, because the CHP Officer Safety Manual

indicates a strong preference for stopping a vehicle on the right

shoulder rather than the median strip, it could not be concluded that

an officer's duty in such circumstances is limited to stopping a

vehicle off the travel lanes, without regard to any other relevant

factor that might affect the reasonableness of the officer's actions.

CA(3) (3) Negligence § 2 —

Definitions and Distinctions — Misfeasance — Nonfeasance: Words,

Phrases, and Maxims — Misfeasance — Nonfeasance.

– Misfeasance exists when the

defendant is responsible for making the plaintiff's position worse,

i.e., the defendant has created the risk. Conversely, nonfeasance is

found then the defendant has failed to aid the plaintiff through

beneficial intervention.

CA(4) (4) Neglience § 10 — Elements

of Actionable Negligence — Duty of Care — Standard of Care — Effect of

Compliance with Statute.

– Even when a defendant has

complied with an applicable statute or regulation, this does not

prevent a finding that a reasonable person would have taken additional

precautions where the situation is such as to call for them.

[See 6 Witkin, Summary of Cal. Law (9th ed. 1988) Torts, § 756.]

CA(5) (5) Negligence § 70 — Actions

— Evidence and Proof — Admissibility of Evidence — Laws, Regulations,

and Ordinances — Highway Patrol Officer Safety Manual.

– Under Evid. Code, § 669.1, the

provisions of the California Highway Patrol Officer Safety Manual may

not properly be viewed as establishing the applicable standard of care,

but they may be considered by the trier of fact in determining whether

an officer was negligent in a particular case. The manual cannot be

read to establish the standard of care, because there is no indication

that the manual was adopted pursuant to the state (or federal)

Administrative Procedure Act. Absent such adoption, Evid. Code, §

669.1, forbids the use of the manual to establish the presumption of

negligence that otherwise would arise under Evid. Code, § 669. At the

same time, Evid. Code, § 669.1, specifies that it is not intended to

affect the admissibility of such a manual into evidence, and thus it is

clear that the manual may be considered as evidence on the question of

negligence.

CA(6) (6) Summary Judgment § 19 — hearing and Determination — Burden of Persuasion.

– A party moving for summary

judgment bears the burden of persuasion that there is no triable issue

of material fact and that the party is entitled to judgment as a matter

of law. There is a triable issue of material fact if the evidence would

allow a reasonable trier of fact to find the underlying fact in favor

of the party opposing the motion in accordance with the applicable

standard of proof.

CA(7) (7) Negligence § 120 — Action — Trial and Judgment — Summary judgment — Existence of Triable Issue.

– In an action against the

California Highway Patrol (CHP) and a CHP officer arising from a

traffic accident in which plaintiffs, occupants of a car that had been

pulled over into a highway median strip by the officer, were struck by

a truck that drifted out of its lane, the trial court erred in finding

that the undisputed evidence established as a matter of law, that the

officer was not negligent. It was undisputed that the median strip was

wider than the right shoulder at this location, that the vehicle

occupied by plaintiffs was traveling in the fast lane and thus a stop

in the median strip did not require it to cross other lanes, and that

the weather and visibility were good. However, in light of the

conflicting evidence relating to the requirements of CHP procedure in

the situation presented, and the circumstance that the evidence

disclosed by the declarations and counterdeclarations could support a

jury's finding that the officer was either summary judgment motion

clearly raised a triable issue for the jury's determination on the

negligence question.

CA(8) (8) Negligence § 19 —

Elements of Actionable Negligence — Proximate Cause — When Intervening

Cause Becomes Superseding Cause — Effect of Truck Driver's Negligence

in Colliding with Car Pulled Over by Highway Patrol.

– In an action against the

California Highway Patrol (CHP) and a CHP officer arising from a

traffic accident in which plaintiffs, occupants of a car that had been

pulled over into a highway median strip by the officer, were struck by

a truck that drifted out of its lane, the trial court's grant of

summary judgment for defendants could not be sustained on the ground

that the officer's conduct was not, as a matter of law, the legal cause

of plaintiff's injuries. The risk of harm posed by the negligence of an

oncoming driver was one of the foremost risks against which the

officer's duty of care was intended to negligent and that his

negligence was a substantial and even predominant cause of plaintiff's

injuries, such a finding would not render the truck driver's conduct a

superseding cause totally eliminating the officer's responsibility for

plaintiffs' injuries. However, such a finding would, under comparative

fault principles, justify the jury's apportioning the bulk of

responsibility for the accident to the truck driver, rather than to the

officer.

Counsel: Law Office of Steven W.

O'Reilly, Charles B. O'Reilly, Steven W. O'Reilly; Haight, Brown &

Bonesteel and Rita Gunasekaran for Plaintiffs and Appellants.

Bill Lockyer, Attorney General,

Pamela Smith-Steward, Chief Assistant Attorney General, Margaret A.

Rodda, Assistant Attorney General, Kristin G. Hogue and Karen M.

Walter, Deputy Attorneys General, for Defendants and Respondents.

Judges: Opinion by George, C. J.,

with Kennard, Werdegar, and Chin, JJ., concurring. Dissenting opinion

by Brown, J., with Baxter, J., concurring (see p. 726).

Opinion by: GEORGE

Opinion

GEORGE, C. J.

Plaintiffs, passengers in an

automobile that had been pulled over by a California Highway Patrol

officer into the center median strip of a highway for a traffic

violation, were injured when a pickup truck ran into their automobile

from behind, while the automobile was stopped in the median strip.

Plaintiffs thereafter filed this personal injury action against (1) the

driver of the pickup truck, (2) the driver of the automobile in which

they were riding, and (3) the California Highway Patrol (CHP) and the

CHP officer who had directed their vehicle to stop in the center

median, alleging that each defendant had been negligent and bore some

legal responsibility for plaintiffs' injuries.

Prior to trial, the CHP and the CHP

officer – the only defendants involved in the appeal now before us

(hereafter generally referred to simply as defendants) – filed a motion

for summary judgment, contending that plaintiffs' action against them

should be dismissed on the ground, among others, that the CHP officer

owed no legal duty of care to plaintiffs. After the parties

filed declarations and counterdeclarations (including a copy of

portions of the applicable CHP Officer Safety Manual), the trial court

granted summary judgment in favor of defendants, based in part upon its

determination that the CHP officer "had no duty to stop plaintiffs on

the right shoulder as a matter of law and there is no triable issue of

fact as to whether [the officer] acted with due care or whether his

conduct was a legal cause of plaintiffs' injuries."

On appeal, the Court of Appeal

reversed, concluding that the CHP officer owed plaintiffs a legal duty

of reasonable care when he directed the driver of the automobile in

which they were riding to stop in a particular location, and that

triable issues of material fact exist as to whether the officer acted

with reasonable care and whether his alleged negligence was a legal

cause of plaintiffs' injuries.

We granted review to consider the

issues presented. As we shall explain, the governing

precedents clearly establish that a law enforcement officer, in

directing a traffic violator to stop in a particular location, has a

legal duty to use reasonable care for the safety of the persons in the

stopped vehicle and to exercise his or her authority in a manner that

does not expose such persons to an unreasonable risk of harm; thus, the

summary judgment in favor of defendants cannot be upheld on the theory

that the CHP officer owed no duty of care to plaintiffs.

Furthermore, although a jury properly could find from the evidence

presented by defendants in support of the summary judgment motion that

the CHP officer was not negligent in directing the automobile in which

plaintiffs were riding to stop in the center median under the

circumstances of this case, we agree with the Court of Appeal that, in

view of the conflicting declarations and the provisions of the CHP

Officer Safety Manual submitted by plaintiffs in opposition to the

summary judgment motion, the issue whether the officer was or was not

negligent cannot properly be resolved by a court as a matter of law and

instead presents a triable issue of fact for the jury's

determination. Accordingly, we conclude that the trial

court erred in granting summary judgment in favor of defendants, and

that the judgment of the Court of Appeal, reversing the trial court's

ruling, should be affirmed.

I

On August 15, 1996, Richard

Hedgecock, a CHP motorcycle patrol officer, was on duty in San Diego

County on Highway 78, a limited access highway with three eastbound and

three westbound lanes. The weather was dry, visibility was good, and

traffic was moderate to fairly heavy. Shortly before 5:00 p.m.,

Hedgecock observed a Toyota Camry traveling westbound at an estimated

speed of 85 miles per hour in the fast, or number one, lane. Hedgecock

pulled his motorcycle along the right side of the Camry, sounded his

siren to attract the attention of its driver, and motioned to the

driver to stop in the center median area of the highway. As directed,

the driver pulled the car over to the left and stopped the Camry in the

center median of the highway. Hedgecock stopped 10 to 15 feet behind

the Camry, close to a two-foot-high concrete barrier separating the

westbound median area from traffic traveling in the eastbound

direction, and turned off the motorcycle's lights.

Hedgecock walked to the driver's

side of the Camry, which was about two feet from the concrete median

barrier. Hedgecock noticed that the three young girls in the backseat

of the Camry (Zean Lugtu, Zeachelle Lugtu, and Leah Cabildo) were not

restrained by seat belts. The driver of the Camry, Michael Lugtu,

identified himself as the uncle of the three girls, and identified the

other passenger in front, Cecelio Lugtu, as the father of two of the

girls. Hedgecock issued a speeding citation to Michael Lugtu and a seat

belt citation to Cecelio Lugtu.

After writing the citations,

Hedgecock noticed that the girl in the middle rear seat still did not

have her seat belt on, and he stated he would issue another citation if

she were not restrained by a seat belt. Michael Lugtu got out of the

Camry, apparently to try to help retrieve the middle rear seat belt, as

Hedgecock began walking back to his motorcycle. The other four

occupants remained within the vehicle. At that point, the Camry had

been stopped in the median area for about six to eight minutes.

As Hedgecock returned to his

motorcycle, he observed a pickup truck, traveling westbound in the fast

lane, begin drifting further and further into the center median toward

Hedgecock and the Camry. As the truck approached, Hedgecock waved and

jumped up and down, trying to attract the attention of the truck's

driver, James Neeb, who appeared to Hedgecock to be looking down inside

the truck. Just as the truck was about to hit him, Hedgecock dove over

the concrete median barrier and heard a very loud crash.

The truck did not hit Hedgecock or

Michael Lugtu, but it struck the rear of the Camry while Cecelio Lugtu

and the three young girls were inside. All four of the car's occupants

were seriously injured in the accident.

In August 1997, Cecelio Lugtu and

the three young girls (plaintiffs) filed the present action against

Hedgecock and the CHP (defendants), Neeb (the driver of the pickup

truck), and Michael Lugtu (the driver of the Camry), alleging that each

was negligent and that the negligence of each was a substantial cause

of plaintiffs' injuries. 1Link to the text of the note

In September 1998, after several

depositions had been taken, defendants filed a motion for summary

judgment, asserting that (1) Hedgecock did not owe a duty of reasonable

care to plaintiffs, (2) as a matter of law, the accident was not

foreseeable and Hedgecock's conduct was not a legal cause of

plaintiffs' injuries, and (3) defendants were statutorily immune from

liability. Defendants maintained that Hedgecock owed no duty of

reasonable care to plaintiffs, because Hedgecock's alleged

responsibility for plaintiffs' injuries arose merely from a failure to

protect plaintiffs from injury (which defendants characterized as a

negligent omission or nonfeasance), and because Hedgecock assertedly

did not have the requisite special relationship with plaintiffs on

which negligence liability for failure to provide such protection could

be based. Defendants also contended that the undisputed facts

established as a matter of law that Hedgecock was not negligent and

that, in any event, his conduct was not a legal cause of plaintiffs'

injuries. Finally, defendants argued that they were immune from

liability under a number of statutory immunity provisions. (See Gov.

Code, § 820.2, 821.6, 845.)

In support of their summary

judgment motion, defendants submitted declarations of Hedgecock and

Arnold Sidney, another CHP officer. Hedgecock stated in his declaration

that he decided to stop the Camry in the 10-foot-wide, asphalt-surfaced

center median because the distance that the Camry had to travel to the

center median was considerably less than the distance to the right

shoulder, and because he believed that stopping the vehicle in the

center median posed a lesser hazard to him and to the Camry's occupants

than stopping the vehicle on the right shoulder, which at that location

was only approximately eight feet wide. 2Link to the text of the note

Hedgecock indicated that at the time he directed the Camry's driver to

pull into the center median, he was aware that there was traffic

immediately behind him in the center lane and "quite a lot of traffic"

in the right-hand lane. Hedgecock also declared that CHP procedures

gave him discretion whether to stop a traffic violator in the median

area or on the right shoulder (the declaration stated that "[i]t is

basically up to the officer to select a safe place to make a traffic

stop"), and that he previously had stopped vehicles in that vicinity in

both the center median and on the right shoulder. Finally, Hedgecock

indicated that at the time he directed the Camry to pull into the

center median, he had no knowledge of prior accidents having occurred

within the center median in that vicinity.

In his separate declaration, Sidney

stated that he had been a CHP officer since 1969, had been trained in

CHP motorcycle patrol procedures, and had been instructed that a

motorcycle patrol officer has discretion to make a traffic enforcement

stop in the median area, particularly if the violator's vehicle is

traveling in the fast lane. Sidney further stated that he subsequently

had received specialized training and had become a certified motorcycle

training officer, and that in 1991 he had trained Hedgecock in CHP

motorcycle patrol procedures and had instructed Hedgecock that a

traffic stop in the median area is appropriate if the violator is in

the fast lane and if the officer believes a stop in the median area is

safer. Sidney's declaration also explains in some detail why, in his

opinion, a stop in the median area may be particularly appropriate when

the stop is made by a motorcycle officer rather than by an officer in a

patrol car. 3Link to the text of the note Finally, Sidney stated that

based upon his review of Hedgecock's declaration, the accident report,

photographs of the accident scene and involved vehicles, and the CHP

Departmental Motorcycle Manual and CHP Officer Safety Manual, in his

opinion Hedgecock had acted reasonably and with a proper exercise of

discretion in directing Michael Lugtu to stop within the center median

area of Highway 78.

In response to defendants' motion

for summary judgment, plaintiffs filed a lengthy opposition. Plaintiffs

initially maintained that defendants' claim that Hedgecock owed no

legal duty of care to plaintiffs rested on a mischaracterization of the

basis of Hedgecock's alleged liability, and asserted that the alleged

negligent conduct of Hedgecock at issue in this case involved an

affirmative act of misfeasance--directing the driver of the vehicle in

which they were passengers to stop the vehicle in an assertedly

dangerous location--rather than an act of omission or nonfeasance as

argued by defendants. Second, plaintiffs insisted that the question

whether Hedgecock had been negligent or instead had exercised due care

in directing the driver of the Camry to stop in the center median could

not be decided as a matter of law, but instead clearly presented a

triable question of fact for the jury's determination. In this regard,

plaintiffs vigorously disputed the assertion in Hedgecock's and

Sidney's declarations that the applicable CHP procedures gave CHP

officers discretion to stop a vehicle either in the center median or on

the right shoulder, maintaining that the applicable CHP Officer Safety

Manual flatly contradicted that assertion by explicitly providing that

"[a]fter determining that a driver is to be stopped, effective

techniques should be used to ensure stopping on the right shoulder

rather than in the median or in a traffic lane." Plaintiffs

additionally asserted that the question whether Hedgecock's negligence

was a legal cause of plaintiff's injuries presented a triable issue of

fact for the jury and could not be determined as a matter of law.

Finally, plaintiffs maintained that the governing precedents

interpreting the statutory immunity provisions relied upon by

defendants established that the immunity afforded by each of those

statutes did not apply to the conduct of defendants at issue in this

case.

In support of their opposition to

the summary judgment motion, plaintiffs submitted a declaration of

Joseph Thompson (a former CHP officer and CHP accident investigation

supervisor), a copy of chapter 10 of the CHP Officer Safety Manual, a

copy of the accident report, and brief excerpts from the depositions of

Hedgecock and Sidney.

Thompson stated in his declaration

that he had been employed by the CHP from 1959 through 1982 both as a

motorcycle and patrol car officer and as an accident investigator and

supervisor, and in the latter capacity had been responsible for

conducting more than 2,000 accident investigations. Thompson stated he

was "extremely familiar" with the CHP Officer Safety Manual in effect

at the time of the accident, and that the manual, and all CHP

motorcycle and patrol car training, "mandate[s] that routine traffic

enforcement stops on California freeways shall be made by directing all

violators over to the right shoulder for purposes of violator and

officer protection." Thompson further stated that "[s]topping a

violator in the center median lane of a California freeway is not

permitted by the [CHP] Officer Safety Manual as this creates a

substantial risk of harm to the violator as well as the patrol officer

due to the increased speed of vehicles in the inside/fast or number one

lane of travel." Thompson's declaration further explained in this

regard that "[t]he center median lane is for emergency vehicles only

and users of the freeway do not expect to see a routine traffic stop

being enforced in the center median lane. The sight of a traffic

enforcement stop being conducted in the center median startles users of

the freeway in the number one or fast lane of traffic causing them to

lose control of their vehicles."

Moreover, in contrast to the views

expressed by Sidney in his declaration, Thompson's declaration stated

that the CHP manuals and training make "no distinction between

motorcycle and patrol car officers in how to make a routine traffic

stop from all lanes of the freeway" (original underlining), and that

nothing in the applicable motorcycle manual allows for officer

discretion in this regard. Finally, Thompson stated in his declaration

that, based upon his review of the depositions of Hedgecock and Sidney,

the accident report, the CHP Departmental Motorcycle Manual, and the

CHP Officer Safety Manual (in particular, chapter 10, pertaining to

patrol and enforcement on the freeway), in Thompson's opinion "Officer

Hedgecock was negligent by violating the California Highway Patrol

enforcement techniques in directing Michael Lugtu to the center median

lane instead of over to the right shoulder," and that in doing so

Hedgecock "substantially increased the risk of harm to the occupants in

the Lugtu vehicle and to the officer."

In addition to Thompson's

declaration, plaintiffs submitted a copy of chapter 10 of the CHP

Officer Safety Manual, entitled Patrol and Enforcement on the Freeway,

which states in relevant part:

"3. Enforcement Techniques.

"a. Stopping the Violator.

"(1) After determining that a

driver is to be stopped, effective techniques should be used to ensure

stopping on the right shoulder rather than in the median or in a

traffic lane. Because of the hazards of high speed and traffic volume

on modern freeways, the officer must be aware of his/her primary

responsibility to control traffic approaching from the rear when

attempting to stop a violator. Under these conditions, one error by a

single driver can cause multiple traffic collisions. Special and unique

methods have been developed which materially reduce the hazards

involved in directing the violator from a high-speed traffic lane to a

position of safety. The following procedures should be used whenever

possible. [P] . . . [P]

"(b) The patrol vehicle should

normally be offset slightly to the right and to the rear of the

violator's vehicle to permit evasive action if it becomes necessary and

also to provide a protected lane for the violator's safe movement to

the right. The rear amber warning light should be used at this time to

warn following traffic of the impending stop. . . .

"(2) When difficulties arise in

gaining [the] violator's attention, it may be necessary to pull

abreast, preferably on the right side, in order to attract the driver's

attention. . . .

"(a) The moment the violator looks

and identifies the patrol unit, the officer should apply the brakes

slightly. No matter how the fast the violator's reflexes are, the

officer then has control of the situation and can slow down as

necessary.

"(b) The driver should be directed

by the use of the hand gesture to the right lane. During a violator's

transition to the right, traffic should be held back in adjacent lanes

by the use of the rear amber light, turn signals and hand gestures. . .

.

"(c) If the driver's attention is

not gained in time to stop at a desired stopping location, he/she

should be permitted to proceed, if practicable, to the next safe

stopping location. . . . [P] . . . [P]

"(3) If possible, ensure a violator

does not stop in the roadway or park in the median divider. All stops

on freeways should be made completely off the roadway and as

inconspicuously as possible to minimize the possibility of a traffic

slowdown. . . .

"(4) When a violator stops in the

center divider, the officer must make a decision whether to handle the

transaction there or request a move to a safer location. Factors to be

considered are divider width, traffic speed, traffic density, and other

surrounding circumstances. The ultimate question is 'Are the hazards of

conducting the stop in the center divider more or less than moving the

violator across multiple freeway lanes?'

"(5) Avoid stopping motorists where

restricted shoulders or heavy congestion exists. The stop should be

delayed until a safe location is reached. . . ." (CHP, Officer Safety

Manual (July 1991 rev.) pp. 10-3 to 10-6, italics added.) 4Link to the

text of the note

Defendants thereafter filed a reply

to the opposition, attaching additional portions of the CHP Officer

Safety Manual that defendants maintained (1) demonstrated that the

manual should not be interpreted, as Thompson had suggested, as

mandating that all traffic stops on a highway be made on the right

shoulder rather than the center median, but rather should be

interpreted to grant a CHP officer discretion in this matter, and (2)

further supported their contention that Hedgecock's conduct was

reasonable and not negligent. 5Link to the text of the note Defendants

also submitted additional excerpts from Sidney's deposition, in which

Sidney stated that when the CHP Officer Safety Manual uses the word

"should" rather than "shall," the manual "is leaving the officer with

an option and his best judgment to do what the situation may call

[for]."

After considering defendants'

motion, plaintiffs' opposition, defendants' reply, and the supporting

declarations and other submitted material, the trial court granted

summary judgment in favor of defendants, concluding that "Hedgecock had

no duty to stop plaintiffs on the right shoulder as a matter of law and

there is no triable issue of fact as to whether Hedgecock acted with

due care or whether his conduct was a legal cause of plaintiffs'

injuries. In addition, even assuming a duty, lack of due care, and

causation, defendants are immune from liability."

On appeal, the Court of Appeal

reversed, concluding that Hedgecock owed plaintiffs a legal duty of

reasonable care when he directed the driver of the Camry to stop the

vehicle in a particular location, and that, in view of the provisions

of the CHP Officer Safety Manual and the conflicting declarations that

were before the trial court, there was a triable issue of fact whether

Hedgecock was negligent and, if so, whether that negligence was a legal

cause of plaintiffs' injuries. Finally, the Court of Appeal concluded

that defendants' claims of statutory immunity lacked merit.

Defendants sought review in this

court, limiting their challenge to the negligence issue, with

particular attention to the Court of Appeal's conclusion on the

question of duty. 6Link to the text of the note We granted review to

address these points.

II

We begin with the issue of duty.

(See generally Davidson v. City of Westminster (1982) 32 Cal. 3d 197,

202-203 [185 Cal. Rptr. 252, 649 P.2d 894].)

Under the provisions of the

California Tort Claims Act, "a public employee is liable for injury

caused by his act or omission to the same extent as a private person,"

except as otherwise specifically provided by statute. ( Gov. Code, §

820 , subd. (a), italics added.) In addition, the Tort Claims Act

further provides that "[a] public entity is liable for injury

proximately caused by an act or omission of an employee of the public

entity within the scope of his employment if the act or omission would

. . . have given rise to a cause of action against that employee,"

unless "the employee is immune from liability." ( Gov. Code, § 815.2,

subds. (a), (b), italics added.) Because it is undisputed that

Hedgecock was acting within the scope of his employment when he engaged

in the conduct at issue in this case, the initial question of duty, and

defendants' potential liability for Hedgecock's conduct, turns on

ordinary and general principles of tort law.

Under general negligence

principles, of course, a person ordinarily is obligated to exercise due

care in his or her own actions so as not to create an unreasonable risk

of injury to others, and this legal duty generally is owed to the class

of persons who it is reasonably foreseeable may be injured as the

result of the actor's conduct. ( Civ. Code, § 1714; see generally

Rest.2d Torts, § 281; Prosser & Keeton on Torts (5th ed. 1984) §

31, p. 169; 3 Harper et al., The Law of Torts (2d ed. 1986) § 18.2, pp.

654-655.) It is well established, moreover, that one's general duty to

exercise due care includes the duty not to place another person in a

situation in which the other person is exposed to an unreasonable risk

of harm through the reasonably foreseeable conduct (including the

reasonably foreseeable negligent conduct) of a third person. (See,

e.g., Schwartz v. Helms Bakery Limited (1967) 67 Cal. 2d 232, 240-244

[60 Cal. Rptr. 510, 430 P.2d 68]; Richardson v. Ham (1955) 44 Cal. 2d

772, 777 [285 P.2d 269]; see generally Rest.2d Torts, §§ 302, 302A.

7Link to the text of the note ) It is this duty that plaintiffs alleged

was breached by Hedgecock.

In their summary judgment motion,

however, defendants asserted that Hedgecock owed no duty of care to

plaintiffs because "[t]he alleged failure of defendant Hedgecock to

protect plaintiffs from injury by defendant Neeb is, at most, a

negligent omission, or nonfeasance," and because there assertedly was

no "special relationship" between Hedgecock and plaintiffs that would

support the imposition of liability on the basis of such an omission.

We agree with plaintiffs that this argument rests upon a fundamental

mischaracterization of the basis of Hedgecock's alleged responsibility

for plaintiffs' injuries.

It is true that the duty plaintiffs

rely upon is said to be restricted to instances of misfeasance, not

nonfeasance. As this court explained in Weirum v. RKO General, Inc.

(1975) 15 Cal. 3d 40, 49 [123 Cal. Rptr. 468, 539 P.2d 36], however,

"[m]isfeasance exists when the defendant is responsible for making the

plaintiff's position worse, i.e., defendant has created a risk.

Conversely, nonfeasance is found when the defendant has failed to aid

plaintiff through beneficial intervention." In this case, unlike the

cases relied upon by defendants, plaintiffs' cause of action does not

rest upon an assertion that defendants should be held liable for

failing to come to plaintiffs' aid, but rather is based upon the claim

that Hedgecock's affirmative conduct itself, in directing Michael Lugtu

to stop the Camry in the center median of the freeway, placed

plaintiffs in a dangerous position and created a serious risk of harm

to which they otherwise would not have been exposed. Thus, plaintiffs'

action against Hedgecock is based upon a claim of misfeasance, not

nonfeasance.

Consistent with the basic tort

principle recognizing that the general duty of due care includes a duty

not to expose others to an unreasonable risk of injury at the hands of

third parties, past California cases uniformly hold that a police

officer who exercises his or her authority to direct another person to

proceed to--or to stop at--a particular location, owes such a person a

duty to use reasonable care in giving that direction, so as not to

place the person in danger or to expose the person to an unreasonable

risk of harm. Thus, for example, in Williams v. State of California

(1983) 34 Cal. 3d 18 [192 Cal. Rptr. 233, 664 P.2d 137], this court

recognized that although law enforcement officers, like other members

of the public, generally do not have a legal duty to come to the aid of

a person, in carrying out routine traffic enforcement duties or

investigations, a duty of care does arise when an officer engages in

"an affirmative act which places the person in peril or increases the

risk of harm as in McCorkle v. Los Angeles (1969) 70 Cal. 2d 252 [74

Cal. Rptr. 389, 449 P.2d 453], where an officer investigating an

accident directed the plaintiff to follow him into the middle of the

intersection where the plaintiff was hit by another car." (34 Cal. 3d

at p. 24, italics added.)

The Court of Appeal recognized this

same principle in Whitton v. State of California (1979) 98 Cal. App. 3d

235 [159 Cal. Rptr. 405, 17 A.L.R.4th 886]. In that case, CHP officers

had made a traffic stop of the plaintiff's automobile on the right

shoulder of a highway, parking their patrol car 10 to 15 feet behind

the plaintiff's vehicle, and a drunk driver subsequently struck the

patrol car, propelling it into the plaintiff while she was standing

between the patrol car and her own vehicle. Although the Court of

Appeal in Whitton found that sufficient evidence supported the jury's

determination that, under the circumstances of the case, the officers

had acted with reasonable care and thus should not be held liable, that

court explicitly recognized that the CHP officers, in making the

traffic stop, had a duty "to perform their official duties in a

reasonable manner." ( Id. at p. 241; see also Reed v. City of San Diego

(1947) 77 Cal. App. 2d 860, 866-867 [177 P.2d 21] [upholding jury

verdict imposing liability upon police department where officers'

negligence in positioning their patrol car during a traffic stop

resulted in an injury to the stopped motorist when a third car collided

with the police vehicle].) Other states also have recognized that law

enforcement officers, in making a traffic stop, have a legal duty to

exercise due care for the safety of those whom they stop and may incur

liability when their failure to exercise such care exposes a person to

injury at the hands of another motorist. (See, e.g., Kaisner v. Kolb

(Fla. 1989) 543 So.2d 732, 734-736; Kinsey v. Town of Kenly (1965) 263

N.C. 376 [139 S.E.2d 686, 688-690].)

Accordingly, we conclude that,

under California law, a law enforcement officer has a duty to exercise

reasonable care for the safety of those persons whom the officer stops,

and that this duty includes the obligation not to expose such persons

to an unreasonable risk of injury by third parties. The summary

judgment in favor of defendants cannot be sustained on the ground that

Hedgecock owed no legal duty of care to plaintiffs.

III

Although defendants argued in their

summary judgment motion that a law enforcement officer in making a

traffic stop on a highway owes no duty of care to the persons he or she

stops, in their briefs before this court defendants have modified their

position and now ask this court to adopt a rule that "the duty of a law

enforcement officer who has made a traffic enforcement stop entirely

off of the travel lanes of a freeway [does] not extend to liability for

a traffic collision in which a third party's vehicle subsequently

strikes the car stopped by the officer."

As this court explained in Ramirez

v. Plough, Inc. (1993) 6 Cal. 4th 539, 546 [25 Cal. Rptr. 2d 97, 863

P.2d 167, 27 A.L.R.5th 899], it is more accurate to view defendants'

present argument not as relating to the threshold question of the

existence of a duty itself--defendants no longer claim that an officer

owes no duty of care to passengers in a vehicle stopped by the

officer--but rather as relating to the appropriate "standard of care."

8Link to the text of the note Defendants argue in essence that we

should declare, as part of the governing standard of care, that a law

enforcement officer, in making a traffic stop on a highway, always

satisfies the duty of reasonable care so long as the officer stops a

vehicle at any location off of the travel lanes of a highway--without

regard to whether the stop is made in the center median of a freeway or

on the right shoulder, and apparently also without regard to the width

of the median or shoulder on which the stop is made, how far off the

roadway the stopped car is located, the visibility of the stopped

vehicle to oncoming traffic at the location of the stop, or any other

potentially relevant circumstance.

From a commonsense perspective,

defendants' proposal has little to recommend it. It is counterintuitive

to suggest that an officer's conduct should be considered prudent

whenever the officer stops a vehicle in the center median of a highway

so long as the vehicle that the officer has stopped is not actually in

the travel lane of the highway, no matter how narrow the center median

strip and how little room there is between the stopped vehicle and the

approaching traffic. Indeed, under the defendants' formulation, a law

enforcement officer's conduct would be deemed to satisfy the duty of

reasonable care even if the center median of a highway is very narrow

and the right shoulder generously wide, and even if there is no barrier

to traffic traveling in the other direction, and the officer chooses

the sole location that is not readily visible to oncoming traffic.

Defendants fail to cite any decision in California or in any other

jurisdiction--and our research has disclosed none--that defines in such

a manner the standard of care applicable to a traffic stop on a highway.

Moreover, defendants are unable to

point to any legislative or administrative pronouncement accepting

their claim that considerations of "public policy" support the rule

they propose. Defendants' reliance upon this court's decision in

Ramirez v. Plough, Inc., supra, 6 Cal. 4th 539, is misplaced. In that

case, we relied upon "the dense layer of state and federal statutes and

regulations that control virtually all aspects of the marketing of [the

defendant drug manufacturer's] products" ( id. at p. 548), as well as

our assessment that "[d]efining the circumstances under which warnings

or other information should be provided in a language other than

English is a task for which legislative and administrative bodies are

particularly well-suited" ( id. at p. 550), in concluding that a drug

manufacturer satisfies its duty to warn of adverse side effects by

providing such warnings in English, as required by the applicable

federal and state regulations. (See fn. 9.), In the present case, by

contrast, no legislative, administrative, or other official

pronouncement indicates that an officer fully satisfies his or her duty

of due care in making a traffic stop so long as the officer stops the

vehicle off the travel lane of a freeway, regardless of the

configuration of the area in which the stop is made or the ready

availability of alternative, safer sites in which the stop could have

been made. 9Link to the text of the note

Indeed, not only is there no

statute or regulation that supports defendants' contention, but the

provisions of the CHP Officer Safety Manual submitted by plaintiffs

appear fundamentally inconsistent with defendants' position. As

indicated by the lengthy quotation set forth above, the CHP Officer

Safety Manual clearly establishes at the very least a general

preference for directing a cited vehicle to the right shoulder of a

highway, rather than to the center median. All of the manual's

references to stops in the median appear to refer only to instances in

which a motorist stops in the center median on his or her own volition,

presumably without the officer's direction to do so. And even in such

instances, the officer is advised to consider directing the driver to

move to a safer location. No provision in the manual establishes that

the officer acts properly or with due care so long as he or she stops a

vehicle entirely within a center median strip.

In considering the effect that the

provisions of the CHP Officer Safety Manual should have in the present

case, it is important to keep in mind the appropriate role that the

provisions of such a safety manual may play in a negligence action

under California law. Under Evidence Code section 669.1, 10Link to the

text of the note the provisions of the CHP Officer Safety Manual may

not properly be viewed as establishing the applicable standard of care,

but they may be considered by the trier of fact in determining whether

or not an officer was negligent in a particular case. The manual cannot

be read to establish the standard of care, because there is no

indication that the manual was adopted pursuant to the state (or

federal) Administrative Procedure Act. Absent such adoption, Evidence

Code section 669.1 forbids the use of the manual to establish the

presumption of negligence that otherwise would arise under Evidence

Code section 669. At the same time, Evidence Code section 669.1

specifies that this statute is not intended to affect the admissibility

of such a manual into evidence, and thus it is clear that the manual

may be considered as evidence on the question of negligence. (See, e.g.

, Bullis v. Security Pac. Nat. Bank (1978) 21 Cal. 3d 801, 809 [148

Cal. Rptr. 22, 582 P.2d 109, 7 A.L.R.4th 642].) 11Link to the text of

the note

Because the relevant provisions of

the CHP Officer Safety Manual submitted by plaintiffs indicate, at the

least, a strong preference for stopping a vehicle on the right shoulder

rather than in the center median, and advise officers to consider

carefully whether to require a motorist to move the vehicle from the

center median even when the driver stops on the center median on his or

her own volition, we cannot accept defendants' assertion that

considerations of public policy support the adoption of a standard of

care under which a CHP officer never could be found to have violated

the duty of care so long as he or she stops a vehicle off the travel

lanes of a freeway, without regard to any other relevant factor that

may affect the reasonableness of the officer's action. Instead, as in

negligence cases generally, we believe that the applicable standard of

care by which the officer's conduct must be measured in this context is

simply that "of a reasonably prudent person under like circumstances."

( Ramirez v. Plough, Inc., supra, 6 Cal. 4th 539, 546-547, and cases

cited.)

In arguing that considerations of

public policy justify the adoption of the narrow standard of care that

they propose, defendants apparently fear that the application of

ordinary negligence principles in the present context will impair the

ability of CHP officers to carry out their responsibilities and will

result in an inordinate financial liability to the state, because

juries will be too ready to second-guess police officers in the

exercise of their discretion in making traffic stops. To the extent

that past cases provide any guidance, this limited precedent does not

support defendants' prediction. As noted above, in Whitton v. State of

California, supra, 98 Cal. App. 3d 235--probably the closest California

case on point--the jury returned a verdict against a plaintiff who had

been injured by a drunk driver as she was stopped for a traffic

violation. The jury found that the CHP officers who had stopped the

plaintiff's car (on the right shoulder of the highway) and, after

detecting alcohol on the plaintiff's breath, conducted a sobriety test

on the plaintiff as she stood between her vehicle and the patrol car,

were not negligent. As Whitton demonstrates, the various considerations

that an officer is required to take into account in deciding when and

where to make a traffic stop, and how to conduct an investigation after

the stop, are not beyond the understanding or experience of most

jurors, and there is little reason to suspect that juries in general

will not grant an officer engaged in law enforcement duties appropriate

leeway in assessing the reasonableness of the officer's conduct.

In sum, we find no justification

for the limitation on the ordinary standard of care that defendants

propose. Of course, if the Legislature determines that the application

of general common law negligence principles in this setting is

undesirable or detrimental, it remains free to fashion an appropriate

response, either through the creation of a statutory immunity or the

promulgation of a legislatively prescribed standard of care. In the

absence of such legislative action, we conclude that the ordinary

negligence standard of care should apply in this context.

IV

Defendants further contend that

even if, as we have concluded above, Hedgecock's conduct must be

evaluated under the ordinary standard of reasonable care, the summary

judgment in their favor should be upheld on the theory that the trial

court correctly found that the undisputed facts establish, as a matter

of law, that Hedgecock was not negligent under that standard. As this

court recently explained in Aguilar v. Atlantic Richfield Co. (2001) 25

Cal. 4th 826, 850 [107 Cal. Rptr. 2d 841, 24 P.3d 493], "the party

moving for summary judgment bears the burden of persuasion that there

is no triable issue of material fact and that he is entitled to

judgment as a matter of law. . . . There is a triable issue of material

fact if . . . the evidence would allow a reasonable trier of fact to

find the underlying fact in favor of the party opposing the motion in

accordance with the applicable standard of proof."

In support of their claim that no

triable issue of fact existed on the question whether Hedgecock was

negligent, defendants stress that it is undisputed that (1) the center

median was wider than the right shoulder at the location where the stop

in this case was made, (2) the Camry was traveling in the fast lane and

thus a stop in the center median did not require the Camry to cross

other lanes of traffic, whereas a stop on the right shoulder would have

required the Camry to cross two lanes of traffic, and (3) the weather

and visibility were good, reducing the risk that oncoming traffic might

not see a stopped vehicle in the median strip.

All of the circumstances upon which

defendants rely clearly are relevant to the determination whether

defendants were negligent and properly could persuade a jury that

Hedgecock was not negligent in stopping the Camry as he did.

Nonetheless, the declarations and other evidence presented by

plaintiffs in opposition to the summary judgment motion constitute

evidence from which a jury could come to a contrary conclusion, thus

raising a triable issue of fact on the question of negligence.

First, the provisions of the CHP

Officer Safety Manual constituted evidence from which a jury could find

that stops in the center median, as a general matter, create a greater

risk of injury than stops on the right shoulder, and that, absent

unusual circumstances, an officer in the exercise of reasonable care

ordinarily should stop a vehicle on the right shoulder. As discussed

above, although under Evidence Code section 669.1 a jury determination

that Hedgecock had violated the provisions of the CHP Officer Safety

Manual would not raise a presumption of negligence, that statute does

not preclude a jury from taking into account the provisions of the

manual in determining whether Hedgecock was or was not negligent under

the circumstances of this case.

Second, the declaration of

Thompson, a former CHP officer and former accident investigator and

investigation supervisor, also constitutes evidence that would support

a jury finding that Hedgecock was negligent. As noted above, Thompson

stated in his declaration that stops in the center median of a highway

pose a greater danger than stops on the right shoulder, because

oncoming vehicles are less likely to expect to see cars or motorcycles

stopped in the center median and thus are more likely to be distracted

by such an event. He further stated that because vehicles traveling in

the left lane of a freeway generally are traveling faster than those in

the right lane, a driver in the left lane is more likely to lose

control of his or her vehicle (and less likely to be able to avoid a

collision) in the event the distraction leads the driver to swerve away

from the stopped vehicle.

Third, a jury might find that

although the existence of circumstances such as bad weather or an

emergency could have made it reasonable for Hedgecock to direct the

Camry to the center median, there was insufficient justification under

the present circumstances for Hedgecock to subject plaintiffs to the

risks inherent in such a stop--especially in view of the good weather

and clear visibility prevailing at the time and location of the stop.

Finally, particularly in light of the provisions of the CHP manual

indicating that if a location is too dangerous the officer should delay

the stop and wait for a safer location, a jury might conclude that if

the width of the right shoulder at the particular area of the highway

was not sufficient to permit the stop to be made safely on the right

shoulder, the officer, in the exercise of reasonable care, should have

permitted the Camry to proceed further and have stopped the vehicle at

a location where the right shoulder was wider. 12Link to the text of

the note

In sum, in light of the conflicting

evidence relating to the requirements of CHP procedure in the situation

presented, and the circumstance that the evidence disclosed by the

declarations and counterdeclarations could support a jury's finding

either that Hedgecock was not negligent or that he was negligent, the

evidence before the trial court on the summary judgment motion clearly

raised a triable issue for the jury's determination on the question of

negligence. Indeed, as we have seen, the declarations of CHP Officer

Sidney and former CHP Officer Thompson--both of whom had many years of

experience in traffic enforcement--were in direct conflict on the

ultimate question of whether Hedgecock was or was not negligent under

the circumstances of this case. On this record, we conclude that the

trial court erred in finding that the undisputed evidence established,

as a matter of law, that Hedgecock was not negligent. 13Link to the

text of the note

V

Finally, defendants argue that even

if a triable issue of fact exists as to whether or not Hedgecock was

negligent, the grant of summary judgment in their favor was nonetheless

proper because even if the jury were to find that Hedgecock was

negligent, the undisputed evidence established, as a matter of law,

that Hedgecock's negligence was not a legal cause of plaintiffs'

injuries. Defendants maintain in this regard that even if the jury were

to find that Hedgecock breached his duty of due care and carelessly

exposed plaintiffs to an unreasonable risk of harm, the conduct of the

driver of the pickup truck--in diverting his eyes from the highway,

drifting into the center median of the freeway, and ultimately

colliding with the Camry--constitutes, as a matter of law, a

superseding cause that relieves Hedgecock of responsibility for

plaintiffs' injuries.

Defendants' contention lacks merit.

It is well established that when a defendant's negligence is based upon

his or her having exposed the plaintiff to an unreasonable risk of harm

from the actions of others, the occurrence of the type of conduct

against which the defendant had a duty to protect the plaintiff cannot

properly constitute a superseding cause that completely relieves the

defendant of any responsibility for the plaintiff's injuries. As the

commentary to the Restatement Second of Torts explains: "The problem

which is involved in determining whether a particular intervening force

is or is not a superseding cause of the harm is in reality a problem of

determining whether the intervention of the force was within the scope

of the reasons imposing the duty upon the actor to refrain from

negligent conduct. If the duty is designed, in part at least, to

protect the other from the hazard of being harmed by the intervening

force, or by the effect of the intervening force operating on the

condition created by the negligent conduct, then that hazard is within

the duty, and the intervening force is not a superseding cause."

(Rest.2d Torts, § 281, com. h, p. 8; see, e.g., Haft v. Lone Palm Hotel

(1970) 3 Cal. 3d 756, 769-770 [91 Cal. Rptr. 745, 478 P.2d 465]; McEvoy

v. American Pool Corp. (1948) 32 Cal. 2d 295, 298-299 [195 P.2d 783].)

As further explained in Soule v. General Motors (1994) 8 Cal. 4th 548

[34 Cal. Rptr. 2d 607, 882 P.2d 298], for an intervening act properly

to be considered a superseding cause, the act must have produced "harm

of a kind and degree so far beyond the risk the original tortfeasor

should have foreseen that the law deems it unfair to hold him

responsible." (Soule, at p. 573, fn. 9, 34 Cal. Rptr. 2d 607, 882 P.2d

298.)

Under these principles, it is clear

that the trial court could not properly find, as a matter of law, that

the conduct of the driver of the pickup truck constituted a superseding

cause that relieves Hedgecock of any legal responsibility for

plaintiffs' injuries. The risk of harm posed by the negligence of an

oncoming driver is one of the foremost risks against which Hedgecock's

duty of care was intended to protect. Accordingly, even if a jury were

to determine that the driver of the pickup truck was negligent and that

his negligence was a substantial and even predominant cause of

plaintiffs' injuries, such a finding would not render the pickup

driver's conduct a superseding cause that totally eliminates

Hedgecock's responsibility for plaintiffs' injuries--although such a

finding certainly would provide ample justification for the jury, in

applying comparative fault principles, to apportion the bulk of

responsibility for the accident to the pickup driver, rather than to

the CHP officer. Indeed, the latter consideration provides a further

reason to discount defendants' claim that a decision in plaintiffs'

favor is likely to subject the state to substantial liability, because

in most cases of this nature the great majority of fault is likely to

be attributed to the third party, and not to the officer. (See Civ.

Code, § 1431.2, subd. (a) ["In any action for personal injury, property

damage, or wrongful death, based upon principles of comparative fault,

the liability of each defendant for non-economic damages shall be

several only and shall not be joint. Each defendant shall be liable

only for the amount of non-economic damages allocated to that defendant

in direct proportion to that defendant's percentage of fault . . . ."].)

Thus, for the reasons discussed

above, we cannot sustain the summary judgment that was rendered in

favor of defendants on the theory that Hedgecock's conduct, as a matter

of law, was not the legal cause of plaintiffs' injuries.

VI

The judgment of the Court of Appeal, reversing the trial court's grant of summary judgment in favor of defendants, is affirmed.

Kennard, J., Werdegar, J., and Chin, J., concurred.

Dissent by: BROWN

Dissent

BROWN, J.

I respectfully dissent.

Like the majority, I agree that a

police officer owes a general duty of care to the passengers in a

vehicle stopped by that officer. I, however, believe the

majority errs in formulating the appropriate standard of

care. Under the undisputed facts, Officer Hedgecock's legal

duty to plaintiffs did not include a duty to stop plaintiffs somewhere

other than the center median of the freeway. Thus, Officer

Hedgecock did not breach his legal duty to plaintiffs as a matter of

law. Accordingly, I would reverse the judgment of the Court of Appeal

and affirm the trial court's grant of summary judgment for defendants.

Like the existence of a legal duty,

the scope of that duty is a question of law for the court. (Merrill v.

Navegar, Inc. (2001) 26 Cal. 4th 465, 477 (Merrill).) In

discussing the scope of Officer Hedgecock's duty, the majority

characterizes the issue as whether an officer "always satisfies" the

duty of care by stopping a traffic violator "at any location off of the

travel lanes of a highway." (Maj. opn., ante, at p. 718.) Relying

exclusively on Ramirez v. Plough, Inc. (1993) 6 Cal. 4th 539 [25 Cal.

Rptr. 2d 97, 863 P.2d 167, 27 A.L.R.5th 899] (Ramirez), the majority

answers "no" because no legislative or administrative pronouncements

support such a rule (maj. opn., ante, at pp. 718-721), and because the

California Highway Patrol Officer Safety Manual (Safety Manual)

indicates "a strong preference for stopping a vehicle on the right

shoulder rather than in the center median" (maj. opn., ante, at p.

721). The majority, however, engages in faulty analysis,

and, in doing so, misstates the issue before the court. The

issue is not whether an officer satisfies his duty of care in every

case by stopping a traffic violator off the lanes of a

highway. Rather, the issue is whether an officer satisfies

his duty of care to the passengers of a car under the uncontested

circumstances of this case when he stops their car in the median area.

The answer should be "yes."

As an initial matter, the majority

mistakenly assumes that the scope of a defendant's duty cannot depend

on the particular facts of a case. "In most cases, courts

have fixed no standard of care for tort liability more precise than

that of a reasonably prudent person under like circumstances."

(Ramirez, supra, 6 Cal. 4th at p. 546.) "[H]owever . . . in

particular situations a more specific standard may be established by

judicial decision, statute or ordinance." (Kentucky Fried Chicken of

Cal., Inc. v. Superior Court (1997) 14 Cal. 4th 814, 824 [59 Cal. Rptr.

2d 756, 927 P.2d 1260].) Thus, " 'each case must be considered on its

own facts to determine' " the scope of the legal duty owed by a

defendant to a class of plaintiffs " 'to refrain from subjecting them

to' " a given risk. (Dillon v. Legg (1968) 68 Cal. 2d 728, 742 [69 Cal.

Rptr. 72, 441 P.2d 912, 29 A.L.R.3d 1316] (Dillon), italics added,

quoting Hergenrether v. East (1964) 61 Cal. 2d 440, 445 [39 Cal. Rptr.

4, 393 P.2d 164].) Indeed, where the facts are undisputed, we have

regularly affirmed summary judgment for a defendant even though the

defendant owed a general duty of care to the plaintiff, because that

general duty did not require the defendant to act any differently under

the facts of the case. (See, e.g., Sharon P. v. Arman, Ltd. (1999) 21

Cal. 4th 1181, 1189-1199 [91 Cal. Rptr. 2d 35, 989 P.2d 121] (Sharon

P.); Parsons v. Crown Disposal Co. (1997) 15 Cal. 4th 456, 477-483 [63

Cal. Rptr. 2d 291, 936 P.2d 70] (Parsons); Thompson v. County of

Alameda (1980) 27 Cal. 3d 741, 753-758 [167 Cal. Rptr. 70, 614 P.2d

728, 12 A.L.R.4th 701] (Thompson); cf. Artiglio v. Corning Inc. (1998)

18 Cal. 4th 604, 616 [76 Cal. Rptr. 2d 479, 957 P.2d 1313] [affirming

summary judgment because there was "no triable issue of fact concerning

the scope of" defendant's duty under Rest.2d Torts, § 324A].)

The majority's second mistake lies

in its exclusive focus on legislative or administrative pronouncements

in formulating the standard of care. When determining the scope of a

defendant's legal duty under the particular facts of a case, courts do

not always rely on legislative or administrative pronouncements, but

weigh all relevant public policy considerations. (See Merrill, supra,

26 Cal. 4th at p. 477.) As part of the weighing process, "

'foreseeability of risk [is] of . . . primary importance. . . .' "

(Dillon, supra, 68 Cal. 2d at p. 739, italics added, quoting Grafton v.

Mollica (1965) 231 Cal. App. 2d 860, 865 [42 Cal. Rptr. 306].)

Foreseeability for purposes of the duty analysis, however, is different

from foreseeability "in the fact-specific sense in which we allow

juries to consider [the] question." (Parsons, supra, 15 Cal. 4th at p.

476, 63 Cal. Rptr. 2d 291, 936 P.2d 70.) "[A] court's task--in

determining 'duty'--is not to decide whether a particular plaintiff's

injury was reasonably foreseeable in light of a particular defendant's

conduct, but rather to evaluate more generally whether the category of

negligent conduct at issue is sufficiently likely to result in the kind

of harm experienced that liability may appropriately be imposed."

(Ballard v. Uribe (1986) 41 Cal. 3d 564, 573, fn. 6 [224 Cal. Rptr.

664, 715 P.2d 624].)

After determining the

foreseeability of harm, courts typically balance foreseeability against

other relevant policy considerations to determine the scope of a

defendant's duty "within the factual context of a specific case."

(Lopez v. McDonald's Corp. (1987) 193 Cal. App. 3d 495, 506 [238 Cal.

Rptr. 436] (Lopez); see also Parsons, supra, 15 Cal. 4th at p. 476.)

Relevant policy considerations include "the degree of certainty that

the plaintiff suffered injury, the closeness of the connection between

the defendant's conduct and the injury suffered, the moral blame

attached to the defendant's conduct, the policy of preventing future

harm, the extent of the burden to the defendant and consequences to the

community of imposing a duty to exercise care with resulting liability

for breach, and the availability, cost, and prevalence of insurance for

the risk involved." (Rowland v. Christian (1968) 69 Cal. 2d 108, 113

[70 Cal. Rptr. 97, 443 P.2d 561, 32 A.L.R.3d 496].) "When public

agencies are involved," courts may also consider " 'the extent of [the

agency's] powers, the role imposed upon it by law and the limitations

imposed upon it by budget.' " (Thompson, supra, 27 Cal. 3d at p. 750,

quoting Raymond v. Paradise Unified School Dist. (1963) 218 Cal. App.

2d 1, 8 [31 Cal. Rptr. 847].) This lengthy list of policy

considerations, however, is neither exhaustive (Lopez, at p. 506), nor

mandatory (see, e.g., Sharon P., supra, 21 Cal. 4th at pp. 1191-1199

[analyzing legal duty without considering all the Rowland factors]; Ann

M. v. Pacific Plaza Shopping Center (1993) 6 Cal. 4th 666, 678-680 [25

Cal. Rptr. 2d 137, 863 P.2d 207] (Ann M.) [same]).

Thus, where the relevant facts are

undisputed, a court may define a more specific standard of care than

the reasonably prudent person standard if the public policy

considerations warrant it. In such cases, the court may be able to

decide the case on summary judgment because the definition of a more

specific standard of care often resolves an interrelated issue: whether

a defendant breached his legal duty of care. " '[T]he question whether

an act or omission will be considered a breach of duty . . .

necessarily depends upon the scope of the duty imposed. . . .' " (

Federico v. Superior Court (1997) 59 Cal. App. 4th 1207, 1211 [69 Cal.

Rptr. 2d 370], quoting Wattenberger v. Cincinnati Reds, Inc. (1994) 28

Cal. App. 4th 746, 751 [33 Cal. Rptr. 2d 732].) If a defendant's

conduct satisfies the standard of care defined by the court as a matter

of law under the undisputed facts of the case, then the defendant, by

definition, has not breached any legal duty. Indeed, some of our early

decisions rely on foreseeability of harm and other policy

considerations to find no breach of a legal duty as a matter of law.