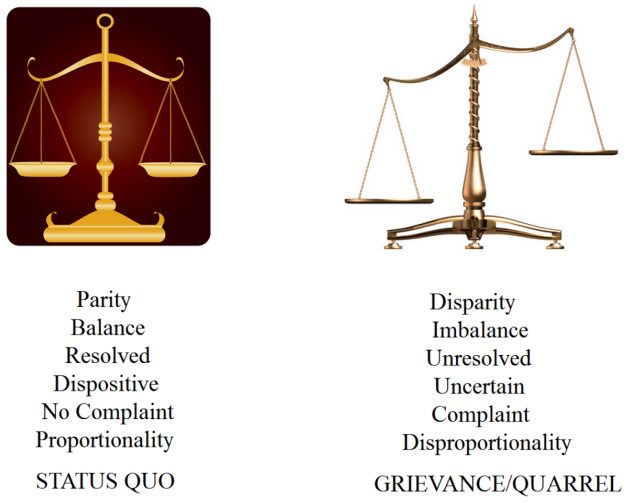

UNRESOLVED DISPUTE/GRIEVANCE

UNRESOLVED DISPUTE/GRIEVANCE

"Common

as the event may be, it is a serious thing to arrest a citizen, and it

is a more serious thing to search his person; and he who accomplishes

it, must do so in conformity to the law of the

land. There

are two reasons for this; one to avoid bloodshed, and the other to

preserve the liberty of the citizen. Obedience to

the law

is the bond of society, and the officers set to enforce the law are not

exempt from its mandates.".

Town

of Blacksburg v. Bean (1916) 104 S.C. 146, 88 S.E. 441

Allen

v. State (1924) 197 N.W. 808, 810-11 (Wis.)

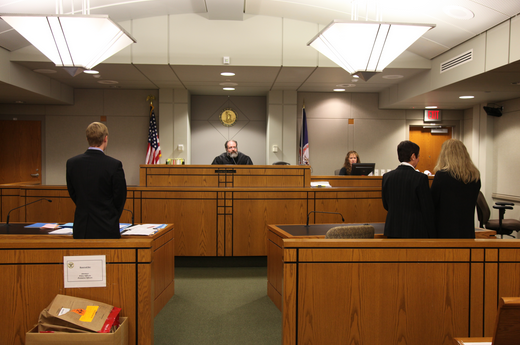

THE PLACE

WHERE UNRESOLVED DISPUTES

ARE RESOLVED WITHOUT

BLOODSHED

THE PLACE

WHERE UNRESOLVED DISPUTES

ARE RESOLVED WITHOUT

BLOODSHED

"The

relevant, dispositive inquiry in determining whether a right is clearly

established is whether it would be clear to a reasonable officer that

his conduct was unlawful in the situation he confronted." (Saucier v.

Katz , supra , 533 U.S. at p. 202.)

Macias

v. County of Los Angeles (2006) 144 Cal.App.4th 313

THE

LAW OF TORTS

William L. Prosser

Professor of Law

Hastings College of Law

FOURTH EDITION

WEST PUBLISHING CO.

1971

Chapter 13

STRICT LIABILITY

p. 492

75. BASIS

OF LIABILITY

¶1:

As we have seen, the early law of torts was not concerned primarily

with the moral responsibility, or “fault” of the

wrongdoer. It

occupied itself chiefly with keeping the peace between individual, by

providing a remedy which would be accepted

in lieu of private vengeance.

This

is the reason we go to court. We want to avoid*...

*

Uncompensated reference

- CRIMINAL ACTION

-

- CRIMINAL ACTION

-

THAT

MUST BE A TRAFFIC INFRACTION CASE.

THERE IS

NO PROSECUTOR BUT THERE IS AN ARRAIGNMENT

THERE IS

NO PROSECUTOR BUT THERE IS AN ARRAIGNMENT

NEITHER THE PEOPLE NOR THEIR ATTORNEY APPEARS

NEITHER THE PEOPLE NOR THEIR ATTORNEY APPEARS

...the

court has no authority to substitute itself as the representative of

the People...

People

v. Orin

(1975) 13 Cal.3d 937

TRANSLATION:

THE COURT HAS NO JURISDICTION...

-

THE RULE OF CONVENIENCE

-

Or how the State shifts its burden of proof to the still

innocent defendant.

THE JOKER IN THE DECK

THE JOKER IN THE DECK

The

court initially stated it thought the People had failed to prove a

violation of Vehicle Code section 12500. The People

referred the court to CALJIC No. 16.631, stating: "I'll refer the Court

to CALJIC 16.631 and the authority cited and that's jury instruction

which indicates the People do not have to prove that the defendant did

not have a license. Since it is a fact that is peculiarly within the

defendant's knowledge."

CALJIC No. 16.631

provides: "It is not necessary for the People to prove that

the

defendant did not have a license [of the appropriate class or [34

Cal.App.4th 197] certification] to operate a motor vehicle. Whether the

defendant was or was not properly licensed is a matter peculiarly

within [his] [her] own knowledge. The burden is on the

defendant

to raise a reasonable doubt as to [his] [her] guilt of driving a motor

vehicle upon a highway without being the holder of a driver's license

[of the appropriate class or certification]."

The

trial court read the instruction, found it to be the correct law, and

concluded that because the matter was within Shawnn's own personal

knowledge, the burden was shifted to Shawnn to prove that he had a

valid license.

[2] Shawnn asserts that the

court erred in relying on CALJIC No. 16.631. Shawnn contends

this instruction is unconstitutional because it improperly shifts the

burden of proof on an element of the crime to the accused.

While

acknowledging the rule of convenience, Shawnn argues that it should not

apply here; whether or not he holds a driver's license is not a fact

peculiarly within his knowledge, and the People have ready and

convenient access to the records of the Department of Motor Vehicles.

Respondent

contends that the rule of convenience applies and views a driver's

license as no different than any other type of license where the rule

has been previously applied.

The rule was

adopted by the California Supreme Court in People v. Boo Doo Hong

(1898) 122 Cal. 606 [55 P. 402]. In Boo Doo Hong the court

followed the general consensus by legal writers that when there are

facts peculiarly and clearly within the knowledge of the defendant, and

the defendant can show the evidence without the least inconvenience,

then the defendant is required to offer this proof. Both of the legal

writings relied on by the court offered license cases as examples. (Id.

at pp. 608-609.) [34 Cal.App.4th 198]

Thus,

the California Supreme Court in Boo Doo Hong clearly held that a

defendant has a burden of producing a license when a license would act

as a complete defense. "As far back as the case of People v. Boo Doo

Hong (1898), 122 Cal. 606 ..., it has been the law that when a license

or prescription would be a complete defense, the burden is upon the

accused to prove that fact so clearly within his knowledge." (People v.

Martinez (1953) 117 Cal.App.2d 701 , 708 [256 P.2d 1028].)

In

People v. Montalvo (1971) 4 Cal.3d 328 [93 Cal.Rptr. 581, 482 P.2d 205,

49 A.L.R.3d 518], the California Supreme Court refused to apply the

rule of convenience to an allegation that a defendant was 21 years of

age or older. "The allegation that the defendant is 21 years of age or

over is not a negative averment. A true negative averment, for example

that the defendant lacked a prescription for a drug, the possession of

which was lawful only on prescription, may often be practically

impossible for the prosecution to prove but easy for the defendant to

refute. In the absence of a legislative provision that minority is a

defense, we do not believe that the relative ability of the prosecution

and defense to establish the defendant's age is sufficient to justify

invoking the rule of necessity and convenience to relieve the

prosecution of its burden of proving the defendant's majority under

section 11502.

"The defendant may not

necessarily have any substantially greater ability to establish his age

than does the prosecution. A defendant's precise age is not a matter

within his personal knowledge but something he must have learned either

from family sources or public or church records. In this age of

documented existence there is little doubt that ordinarily the

prosecution may be able to secure evidence of the defendant's age.

Moreover, in those rare cases where there is no evidence of the

defendant's precise age except his own belief as to what it is, the

defendant might be as hard pressed as the prosecution to verify it. If

minority be deemed a defense, a defendant in such a case would be at

the mercy of the jury's power to disbelieve his testimony even though

it be the only available evidence of age. We conclude that a case for

the application of the rule of necessity and convenience here has not

been made out." (People v. Montalvo, supra, 4 Cal.3d at pp. 334-335.)

Driving

without a valid driver's license is a negative averment just as

possessing a controlled substance without a prescription has been held

to be. Holding a valid driver's license is a matter within the

defendant's personal knowledge and it would not be unduly harsh or

inconvenient for a defendant to produce the license. The California

Supreme Court in Boo Doo Hong specifically endorsed the rule in license

cases.

The one factor urged by Shawnn as a

reason to not apply the rule of convenience is that the People have

ready access to driver's license records [34 Cal.App.4th 199] in

California. We cannot ignore that much has changed since 1898 in

technology and that access to particular types of information can often

be achieved with little or no inconvenience in a very short period of

time. Yet there is insufficient evidence before us from which we can

determine how easily accessible and producible in admissible form this

information is to the People. Because the Supreme Court's ruling in Boo

Doo Hong continues to be good law, and because of the lack of evidence

as to the People's access to driver's license information, we choose

not to deviate from the well-established principle of applying the rule

of convenience to cases involving licenses.

Shawnn

failed to produce his driver's license when asked to do so. Sergeant

Ruckman ran Shawnn's name through a Department of Motor Vehicles check

and was advised that Shawnn did not have a valid license. At trial,

Shawnn failed to produce any evidence that he possessed a valid

driver's license. Shawnn failed to show he was a licensed driver.

In re

Shawnn

F. (1995) 34 Cal.App.4th 184

THE

PEOPLE, Respondent, v. BOO DOO HONG, Appellant

Crim. No. 420

Supreme Court of California, Department Two

122 Cal. 606; 55 P. 402; 1898 Cal. LEXIS 641

December 8, 1898

PRIOR-HISTORY:

APPEAL from a judgment of the Superior Court of Tehama County and from

an order denying a new trial.

John F. Ellison, Judge.

COUNSEL: J. T. Matlock, for Appellant.

W. F. Fitzgerald, Attorney-General, and C. N.

Post, Deputy Attorney-General, for Respondent.

JUDGES: Belcher, C. Haynes, C., and Searls, C.,

concurred. Henshaw, J., McFarland, J., Temple, J.

OPINION BY: BELCHER

OPINION

The

defendant was charged by information, filed in the superior court of

Tehama County, with the crime of willfully and unlawfully practicing

medicine in the state of California, without having first procured a

certificate to so practice as required by law. He demurred to the

information, and, his demurrer being overruled, then pleaded not

guilty. He was subsequently tried and found guilty of the offense

charged, and judgment was entered that he pay a fine of three hundred

and fifty dollars, et cetera. From that judgment and an order denying

his motion for a new trial he has appealed.

The demurrer was

properly overruled. The facts stated in the information were sufficient

to constitute a public offense, and it was not necessary to allege the

existence of the medical societies referred to. ( People v. O'Leary, 77

Cal. 30.)

At the trial uncontradicted evidence was

introduced by

the prosecution sufficiently showing that for several months prior to

the filing of the information defendant had been practicing medicine at

Red Bluff, in the county of Tehama ( People v. Lee Wah, 71 Cal. 80),

but no evidence was introduced on either side showing, or tending to

show, that defendant had or had not a certificate to so practice, as

required by law. (Stats. 1875-76, p. 792; Stats. 1877-78, p. 918.) And

at the conclusion of the evidence the court instructed the jury quite

fully upon all the questions of law involved in the case, and, among

other things, told them, in effect, that the burden was upon the

defendant to establish that he had a certificate to practice medicine

as provided by law, and, if he failed to prove that he had such

certificate, then it must be taken as true that he had not procured a

certificate to so practice medicine.

It is contended for

appellant that the said instruction was erroneous and misleading, and

that the verdict was not justified by the evidence, because in a

criminal action the defendant is presumed to be innocent until he is

proved guilty beyond a reasonable doubt, and this presumption continues

through the entire trial, and the burden is upon the people to

establish his guilt by proving every material allegation of the

information; and that as the information charged that defendant had

practiced medicine without having a certificate to do so, it devolved

upon the people to prove that fact, and having entirely failed to offer

any such proof he ought not to have been convicted, and his motion for

new trial should have been granted.

The general rule is

undoubtedly as above stated, but there is a well recognized exception

to the rule, where there is a negative averment of a fact which is

peculiarly within the knowledge of the defendant.

Mr. Greenleaf,

in his work on Evidence, volume 1, section 79, under the heading

"Negative Allegations," says: "But when the subject matter of a

negative averment lies peculiarly within the knowledge of the other

party, the averment is taken as true unless disproved by that party.

Such is the case in civil or criminal prosecutions for a penalty for

doing an act which the statutes do not permit to be done by any

persons, except those who are duly licensed therefor; as, for selling

liquors, exercising a trade or profession, and the like. Here the

party, if licensed, can immediately show it without the least

inconvenience; whereas, if proof of the negative were required, the

inconvenience would be very great." (Citing a large number of cases.

See, also, 3 Rice on Evidence, sec. 260, where the same rule is

declared.)

In 1 Jones' Law of Evidence, section 179, under

the

heading "Burden as to particular facts lying peculiarly within

knowledge of a party," it is said: "This is often illustrated in

prosecutions for selling liquors or doing other acts without the

license required by law. By a few authorities the rule is prescribed

that in such cases the prosecution must offer some slight proof of the

fact that no license has been granted, for example, by producing the

book in which licenses are recorded; and, if the book fails to show

that a license has been granted, the burden is shifted upon the

defendant to prove the fact claimed by him; but the greater number of

authorities hold that where a license would be a complete defense the

burden is upon the defendant to prove the fact so clearly within his

own knowledge." (Citing cases.)

We think the rule upon this

subject generally recognized and followed the correct one, and

therefore conclude that the court did not err in giving the instruction

complained of, and that the verdict was justified by the evidence.

The judgment and order appealed from should be

affirmed.

For the reasons given in the foregoing opinion

the judgment and order appealed from are affirmed.

Q:

WHAT'S A LAWYER?

A: A

MECHANIC WITH CLEAN FINGERNAILS

A: A

MECHANIC WITH CLEAN FINGERNAILS

A lawyer

is a mechanic.

They fix things. There’s repair manuals for their

trade. Their repair manuals are located at the Law

Library. Lots of repair manuals are also on-line so

anyone

can read them to determine if the mechanic knows what they’re doing.

The

primary tools of the

mechanic’s trade are his eyes, brain, mouth, and

fingers.

Presumably if you have these tools you too could do what the lawyer

does. It’s helpful to have a typewriter or computer with a

printer.

The

lawyer mechanic primarily

fixes misunderstandings and disagreements. That’s

something

anyone with a mouth and semi-functional brain can do.

If you don't show up after

promising to show up, you lose.

Neither the People, who are the alleged victim, nor their attorney, the

District Attorney, bothers to show up to tend their case.

Their

case must be on ...

WE WIN!

Is that how it works?

You're accused of an alleged crime and neither the plaintiff

nor

their attorney appear, in fact they don't even file a complaint.

This is your Justice System. It was set up to benefit the

People. The Founders would not have set up a system

they

risked their lives and the lives of their families to recreate what

they went to war and defeated.

Seriously, who prosecutes the

CRIMINAL CASE? Who filed the CRIMINAL CASE?

Who's

the witness in the CRIMINAL CASE? What does the Accuser HAVE

TO do?

[4]

Whether or not the People provide a prosecuting attorney, the citing

officer who testifies as to the circumstances of the citation is a

witness, no more, no less.

People

v.

Marcroft (1992) 6 Cal.App.4th Supp. 1

Appellate Department, Superior Court, Orange

Actori

incumbit onus probandi

The burden of proof lies on the plaintiff.

Defendant

makes a prima facie case of unlawful arrest when he establishes that

arrest was made without a warrant, and burden rests on prosecution to

show proper justification.

People

v.

Holguin (1956) 145 Cal.App.2d. 520

If

objection to illegal arrest may be raised at all after accused has

subjected himself to the jurisdiction of the court, the issue must at

least be raised before a plea is entered at arraignment.

Ringer

v. Municipal Court of Modesto Judicial Dist., Stanislaus County

(1959) 175 C.A.2d 786

THE ACCUSER

BEARS THE BURDEN OF

PROOF

CALIFORNIA EVIDENCE

CODE

THE ACCUSER

BEARS THE BURDEN OF

PROOF

CALIFORNIA EVIDENCE

CODE

SECTION 520

NO CONVICTION!

NO CONVICTION!

Defendant

makes a prima facie case of unlawful arrest when he establishes that

arrest was made without a warrant, and burden rests on prosecution to

show proper justification.

People

v.

Holguin (1956) 145 Cal.App.2d. 520

Defendant

notes that the prosecution has the burden of proving, if it can, some

justification for a warrantless search or seizure, and therefore a

warrantless search is presumptively unreasonable.

...once defendant had properly raised the issue,

the prosecution had the burden of proof.

The prosecution retains the burden of proving

that the warrantless search or seizure was reasonable under the

circumstances.

People

v.

Williams (1999) 20 Cal. 4th 119

Q: WHAT'S A JUDGE?

Q: WHAT'S A JUDGE?

A: AN UMPIRE

The

Judicial Officer is not the Defendant's adversary. The

Defendant's

adversary is the District Attorney or City Attorney or private citizen.

The judicial officer is the umpire. They play for

neither team.

THEY KNOW

THE RULES. SHOULDN'T

YOU?

THEY KNOW

THE RULES. SHOULDN'T

YOU?

JUDGE’S

MANDATORY DUTY

DO NOT ARGUE WITH THE JUDICIAL OFFICER.

DISQUALIFY THEM!

DO NOT ARGUE WITH THE JUDICIAL OFFICER.

DISQUALIFY THEM!

Code

of Civil Procedure

170.1. (a) A

judge shall be disqualified if any one or more of the following is true:

(2) (A)

The judge served as a lawyer in the proceeding,

(6) (A) For

any reason:

(iii) A

person aware of the facts might reasonably entertain a doubt that the

judge would be able to be impartial.

HEARSAY AND FOUNDATION! ASSUMES FACTS

NOT IN EVIDENCE

HEARSAY AND FOUNDATION! ASSUMES FACTS

NOT IN EVIDENCE.

Your

Honor, the question assumes

facts not in evidence. We are here to ask for

facts from

the witnesses, not assume that a fact exists.

Your

Honor, we object to the lack

of foundation because [e.g., there is no showing of the witness’s time

and place of observation of the facts called for].

“An

objection to foundation is futile unless it is sufficiently specific to

afford the opposing party opportunity to cure it.”

United

States

v. Michaels, 726 F.2d 1307, 1314 (8th Cir. 1984)

It

is the duty of courts to be watchful for the constitutional rights of

the citizen, and against any stealthy encroachments thereon.

Their motto should be obsta principiis.

BOYD v.

U.S.

(1886) 116 U.S. 616

Judge has obligation to impose contempt and

swiftly punish those who attempt to win by disobeying rules.

Betsworth

v.

W.C.A.B. (1994) 26 Cal.App.4th 586

When

a person is clothed with power and has assumed the duties of a public

officer, he has taken upon himself the obligation to perform those

duties; and if he neglects or refuses to do so, any person, whose

rights thereby injuriously affected, is entitled to demand relief, and

mandamus is the proper remedy.

Sinton

v.

Ashbury (July 1871) 41 Cal. 526

California

Government Code

72190.

Within the jurisdiction of the court and under the direction of the

judges, commissioners shall exercise all the powers and perform all of

the duties prescribed by law. At the direction of the judges,

commissioners may have the same jurisdiction and exercise the same

powers and duties as the judges of the court with respect to any

infraction or small claims action. They shall be ex officio

deputy clerks.

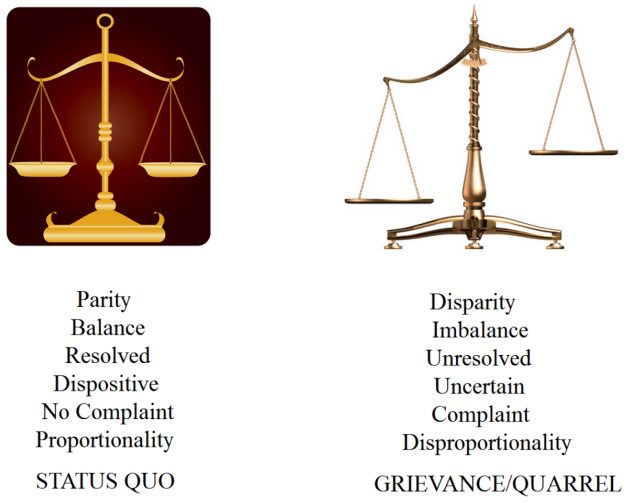

BURDEN OF PROOF:

CRIME:

BURDEN OF PROOF:

CRIME:

PROOF

ESTABLISHED WITH SUFFICIENT

EVIDENCE BEYOND A REASONABLE DOUBT THE ACCUSED COMMITTED A CRIME

YOUR

ACCUSER DOES NOT WIN UNLESS THEY PUT STUFF IN THEIR SIDE OF THE SCALE

THAT MAKES IT GET CLOSER TO THE DESK TOP THAN WHAT YOU PUT IN

YOUR SIDE OF THE SCALES.

CRIME

CALIFORNIA

GOVERNMENT CODE

13951(b)(1).

"Crime"

means a crime or public offense, wherever it may take place, that would

constitute a misdemeanor or a felony if the crime had been committed in

California by a competent adult.

In

View of Code Civ. Proc. §24, declaring actions to be two kinds, civil

and criminal, and §22, defining actions, there is no such thing as a

“quasi-criminal act.”

Ex

Parte Clark (1914), 24 C.A. 389

All crimes are against the state.

People v. Weber (1948) 84 C.A.2d 126

A

"public

offense" is synonymous with "a crime" and a crime includes both

felonies and misdemeanors.

Burks v. United States, 287 F.2d 117

(9th Cir.1961).

Prosecution

must establish that a crime has been committed.

People v. Brower

(1949) 92 C.A. 2d 562

Are based on rules that are printed and are

on-line.

Are based on rules that are printed and are

on-line.

ONLY THE

ATTORNEY GENERAL OR

DISTRICT ATTORNEY ARE

ONLY THE

ATTORNEY GENERAL OR

DISTRICT ATTORNEY ARE

AUTHORIZED BY THE LEGISLATURE TO PROSECUTE CRIMINAL ACTIONS

THE

DISTRICT ATTORNEY HAS THE PREROGATIVE TO PROCECUTE AN ALLEGED CRIME

THE

DISTRICT ATTORNEY HAS THE PREROGATIVE TO PROCECUTE AN ALLEGED CRIME

THE

DISTRICT ATTORNEY IS NOT REQUIRED TO PROSECUTE AN ALLEGED CRIME

THE

DISTRICT ATTORNEY IS NOT REQUIRED TO PROSECUTE AN ALLEGED CRIME

The

investigation and prosecution of public offenses is, of course, the

responsibility and prerogative of the Attorney General and the several

district attorneys (Cal. Const., art. V, § 13; Gov. Code, § 26500), and

no one may intrude upon these activities without the concurrence,

approval, or authorization of such officers. (Dix v. Superior Court

(1991) 53 Cal.3d 442, 451 [279 Cal.Rptr. 834, 807 P.2d 1063]; People ex

rel. Kottmeier v. Municipal Court (1990) 220 Cal.App.3d 602, 609 [269

Cal.Rptr. 542]; People v. Shults (1978) 87 Cal.App.3d 101, 106 [150

Cal.Rptr. 747]; Hicks v. Board of Supervisors (1977) 69 Cal.App.3d 228,

240-241 [138 Cal.Rptr. 101].)

Los Angeles City Ethics Com. v.

Superior Court (Fuentes) (1992) 8

Cal.App.4th 1287

The

prosecution of criminal offenses on behalf of the People is the sole

responsibility of the public prosecutor. (Gov. Code, §§ 26500, 26501;

see Cal. Const., art. V, § 13.)

[2] The prosecutor ordinarily

has sole discretion to determine whom to charge, what charges to file

and pursue, and what punishment to seek. (E.g., People v. Sidener

(1962) 58 Cal.2d 645, 650 [25 Cal.Rptr. 697, 375 P.2d 641].) No private

citizen, however personally aggrieved, may institute criminal

proceedings independently (e.g., Rosato v. Superior Court (1975) 51

Cal.App.3d 190, 226 [124 Cal.Rptr. 427]), and the prosecutor's own

discretion is not subject to judicial control at the behest of persons

other than the accused. (People v. Wallace (1985) 169 Cal.App.3d 406,

410 [215 Cal.Rptr. 203]; Hicks v. Board of Supervisors (1977) 69

Cal.App.3d 228, 240-241 [138 Cal.Rptr. 101]; Taliaferro v. Locke (1960)

182 Cal.App.2d 752, 755-757 [6 Cal.Rptr. 813].) An individual exercise

of prosecutorial discretion is presumed to be " 'legitimately founded

on the complex considerations necessary for the effective and efficient

administration of law enforcement. ...' " (People v. Keenan (1988) 46

Cal.3d 478, 506 [250 Cal.Rptr. 550, 758 P.2d 1081], quoting People v.

Heskett (1982) 30 Cal.3d 841, 860 [180 Cal.Rptr. 640, 640 P.2d 776].)

[53 Cal.3d 452]

Exclusive prosecutorial discretion must also

extend to the conduct of a criminal action once commenced. "In

conducting a trial a prosecutor is bound only by the general rules of

law and professional ethics that bind all counsel." (Taliaferro v.

Locke, supra, 182 Cal.App.2d at p. 756.) The prosecutor has the

responsibility to decide in the public interest whether to seek,

oppose, accept, or challenge judicial actions and rulings. These

decisions, too, go beyond safety and redress for an individual victim;

they involve "the complex considerations necessary for the effective

and efficient administration of law enforcement." There is no place in

this scheme for intervention by a victim pursuing personal concerns

about the case.

Dix v.

Superior Court (People) (1991) 53 Cal.3d 442

Thus

the theme which runs throughout the criminal procedure in this state is

that all persons should be protected from having to defend against

frivolous prosecutions and that one major safeguard against such

prosecutions [27 Cal.App.3d 206] is the function of the district

attorney in screening criminal cases prior to instituting a

prosecution. fn. 8

Due

process of law requires that criminal prosecutions be instituted

through the regular processes of law. These regular processes include

the requirement that the institution of any criminal proceeding be

authorized and approved by the district attorney.

People v. Municipal Court

(Pellegrino) (1972),

27

Cal.App.3d 193

We get to make up our own rules!

We get to make up our own rules!

Why

weren't you invited to participate in the development of the

"innovative procedures"? How do you know they benefit you?

How do you know what rules to use when you're subjected to

the

"innovative system" the courts and attorneys have developed if you

decide to have your day in court because you believe the officer may be

wrong? How will you know what procedures to use to go about

fixing your problem?

Fortunately the codes are available on-line 24/7 so there's no reason

for anyone to claim they didn't know the law. What

commissioner

or judge would buy the "Gee,

I didn't know your honor." defense, due to the fact they

KNOW the codes are avaliable for access 24/7 365?

Government was created by

the people for the people, not by the people for the government

employees. It's an absurd proposition that the employees have more

power than the employer. Hence, the importance of knowing

the

rules applicable to the employees and their job description.

Even

if the officer is not expected to know the law of all 50 states, surely

he is expected to know the California Vehicle Code,...

THE

PEOPLE v.

JESUS SANTOS SANCHEZ REYES (2011) 196 Cal.App.4th 856,

COURT OF APPEAL OF THE STATE OF CALIFORNIA

Both the police we honor

and the criminals we prosecute are subject to the same binding

Constitution.

SMITH v.

CITY

OF HEMET, 394 F.3d 689 (9th Cir. 2005) (en banc)

Police

officer may not rely on good faith, inarticulable hunches, or

generalized suspicions to meet standard of reasonable suspicion to

justify investigatory stop.

U.S.

v. Velarde, 823 F. Supp. 792. (D.

Hawaii 1993)

“To

punish a person because he has done what the law plainly allows him to

do is a due process violation of the most basic sort.”

Bordenkircher v. Hayes, 434 US 357, 363

(1978)

U.S. v.

Goodwin, 457 US 368, 372 (1982)

If

the averments contained in the affidavit are true, it may be that the

present complaint was drawn so as to get past a demurrer, and so as to

get to trial on a purely fictitious and nonexistent cause of action.

If so, it constitutes an abuse of judicial process.

To

take up the time of the courts with an action known by the attorney to

be false and fictitious is clearly an abuse of judicial process.

The courts involved are not impotent to protect themselves from such

imposition. They possess inherent powers to prevent the administration

of justice from being brought into disrepute by such tactics, [67

Cal.App.2d 897] and specifically may use the implied power "to properly

and effectively function as a separate department in the scheme of our

state government" (Brydonjack v. State Bar, 208 Cal. 439 [281 P. 1018,

66 A.L.R. 1507]) to supervise and discipline "the conduct of attorneys

who are officers of the court." (Barton v. State Bar, 209 Cal. 677, 681

[289 P. 818].) These powers do not depend upon

constitutional

grant but arise from the inherent power "necessary to the orderly and

efficient exercise of jurisdiction." (14 Am.Jur., pp. 370, 372, § 171.)

If

upon such a hearing it develops that there has been a deliberate

intentional abuse of the judicial processes by counsel for appellant,

the trial court possesses full and complete powers to punish such abuse

by contempt proceedings or otherwise.

Corum v.

Hartford Acc. & Ind. Co., 67 Cal.App.2d 891

[Civ. No. 12705. First Dist., Div. One. Feb. 9,

1945.]

Government

officials performing discretionary functions “are shielded from

liability for civil damages insofar as their conduct does not violate

clearly established statutory or constitutional rights of which a

reasonable person would have known.” Harlow, 457 U.S. at 818,

102

S.Ct. 2727.

Mary

CLEMENT, Plaintiff-Appellant, v. CITY OF GLENDALE, Defendant, J

& E

Service Inc., d/b/a Monterey Tow Service; J. Young, an

individual, Defendants-Appellees. (2008), No. 05-56692,

9th Circuit Court of Appeals

Was there

an actual violation.

When you're exercising clearly established constitutionally

secured rights you're immune from arrest and criminal prosecution for

crime.

"The

relevant, dispositive inquiry in determining whether a right is clearly

established is whether it would be clear to a reasonable officer that

his conduct was unlawful in the situation he confronted." (Saucier v.

Katz , supra , 533 U.S. at p. 202.)

Macias

v.

County of Los Angeles (2006) 144 Cal.App.4th 313

Of

course this is "dispositive" because when you're exercising clearly

established rights you're not harming anyone nor breaking any rule.

So that seems to be the first order of business.

If

the arrest was illegal, where's a better place to report it than open

court in front of a judicial officer while the interaction is being

officially recorded? And who says you

have to have a jerk for a judge?

Title 28, United States Code,

Part I, Chapter 21, §455 Disqualification of justice, judge, or

magistrate judge

(a)

Any justice, judge, or magistrate judge of the United States shall

disqualify himself in any proceeding in which his impartiality might

reasonably be questioned.

(b) He shall also disqualify himself in the following

circumstances:

(1) Where he has a personal bias or prejudice concerning a party, or

personal knowledge of disputed evidentiary facts concerning the

proceeding;

(2) Where in private practice he

served as lawyer in the matter in controversy, or a lawyer with whom he

previously practiced law served during such association as a lawyer

concerning the matter, or the judge or such lawyer has been a material

witness concerning it;

(3) Where he has served in

governmental employment and in such capacity participated as counsel,

adviser or material witness concerning the proceeding or expressed an

opinion concerning the merits of the particular case in controversy;

(4) He knows that he, individually or as a fiduciary, or his spouse or

minor child residing in his household, has a financial interest in the

subject matter in controversy or in a party to the proceeding, or any

other interest that could be substantially affected by the outcome of

the proceeding;

(5) He or his spouse, or a person

within the third degree of relationship to either of them, or the

spouse of such a person:

(i) Is a

party to the proceeding, or an officer, director, or trustee of a party;

(ii) Is

acting as a lawyer in the proceeding;

(iii) Is known by the judge to have an

interest that

could be substantially affected by the outcome of the proceeding;

(iv) Is

to the judge’s knowledge likely to be a material witness in the

proceeding.

(c)

A judge should inform himself about his personal and fiduciary

financial interests, and make a reasonable effort to inform himself

about the personal financial interests of his spouse and minor children

residing in his household.

(d) For the purposes of this section the following words or

phrases shall have the meaning indicated:

(1) “proceeding” includes pretrial,

trial, appellate review, or other stages of litigation;

(2) the degree of relationship is

calculated according to the civil law system;

(3) “fiduciary” includes such

relationships as executor, administrator, trustee, and guardian;

(4) “financial interest” means ownership of a legal or equitable

interest, however small, or a relationship as director, adviser, or

other active participant in the affairs of a party, except that:

(i) Ownership in a mutual or common

investment fund

that holds securities is not a “financial interest” in such securities

unless the judge participates in the management of the fund;

(ii) An office in an educational,

religious,

charitable, fraternal, or civic organization is not a “financial

interest” in securities held by the organization;

(iii) The proprietary interest of a

policyholder in

a mutual insurance company, of a depositor in a mutual savings

association, or a similar proprietary interest, is a “financial

interest” in the organization only if the outcome of the proceeding

could substantially affect the value of the interest;

(iv) Ownership of government securities

is a

“financial interest” in the issuer only if the outcome of the

proceeding could substantially affect the value of the securities.

(e) No justice, judge, or magistrate judge shall accept from

the

parties to the proceeding a waiver of any ground for disqualification

enumerated in subsection (b). Where the ground for disqualification

arises only under subsection (a), waiver may be accepted provided it is

preceded by a full disclosure on the record of the basis for

disqualification.

(f) Notwithstanding the

preceding provisions of this section, if any justice, judge, magistrate

judge, or bankruptcy judge to whom a matter has been assigned would be

disqualified, after substantial judicial time has been devoted to the

matter, because of the appearance or discovery, after the matter was

assigned to him or her, that he or she individually or as a fiduciary,

or his or her spouse or minor child residing in his or her household,

has a financial interest in a party (other than an interest that could

be substantially affected by the outcome), disqualification is not

required if the justice, judge, magistrate judge, bankruptcy judge,

spouse or minor child, as the case may be, divests himself or herself

of the interest that provides the grounds for the disqualification.

(June 25, 1948, ch. 646, 62 Stat. 908; Pub. L. 93–512, § 1, Dec. 5,

1974, 88 Stat. 1609; Pub. L. 95–598, title II, § 214(a), (b), Nov. 6,

1978, 92 Stat. 2661; Pub. L. 100–702, title X, § 1007, Nov. 19, 1988,

102 Stat. 4667; Pub. L. 101–650, title III, § 321, Dec. 1, 1990, 104

Stat. 5117.)

CALIFORNIA GOVERNMENT CODE

19572. Each of the following constitutes cause for

discipline of an employee, or of a person whose name appears on any

employment list:

(a) Fraud in

securing appointment.

(b) Incompetency.

(c)

Inefficiency.

(d) Inexcusable

neglect of duty.

(e) Insubordination.

(f) Dishonesty.

(g) Drunkenness on

duty.

(h) Intemperance.

(i) Addiction to

the use of controlled substances.

(j) Inexcusable

absence without leave.

(k) Conviction of a

felony or conviction of a misdemeanor involving moral turpitude. A plea

or verdict of guilty, or a conviction following a plea of nolo

contendere, to a charge of a felony or any offense involving moral

turpitude is deemed to be a conviction within the meaning of this

section.

(l) Immorality.

(m) Discourteous

treatment of the public or other employees.

(n) Improper

political activity.

(o) Willful

disobedience.

(p) Misuse of state

property.

(q) Violation of

this part or of a board rule.

(r) Violation of

the prohibitions set forth in accordance with Section 19990.

(s) Refusal to take

and subscribe any oath or affirmation that is required by law in

connection with the employment.

(t) Other failure

of good behavior either during or outside of duty hours, which is of

such a nature that it causes discredit to the appointing authority or

the person's employment.

(u) Any negligence,

recklessness, or intentional act that results in the death of a patient

of a state hospital serving the mentally disabled or the

developmentally disabled.

(v) The use during

duty hours, for training or target practice, of any material that is

not authorized for that use by the appointing power.

(w) Unlawful

discrimination, including harassment, on any basis listed in

subdivision (a) of Section 12940, as those bases are defined in

Sections 12926 and 12926.1, except as otherwise provided in Section

12940, against the public or other employees while acting in the

capacity of a state employee.

(x) Unlawful

retaliation against any other state officer or employee or member of

the public who in good faith reports, discloses, divulges, or otherwise

brings to the attention of, the Attorney General or any other

appropriate authority, any facts or information relative to actual or

suspected violation of any law of this state or the United States

occurring on the job or directly related to the job.

Everyone on the government payroll is an employee, including police,

dirstrict attorneys, judges and everyone else working there.

I guess

none of that

means what it says because if it did then we’d have to admit we’ve been

pretty screwed over for a very long time by people who should know

better and haven’t lifted a finger to do anything about

it.

Infractions are not crimes. There is no probable

cause for

a valid warrantless arrest given the conduct in question was not a

crime.

Then

there's that commercial aspect of the allegation that must be

proved with sufficient evidence that one was involved in commerce at

the time the officer determined a violation had occurred.

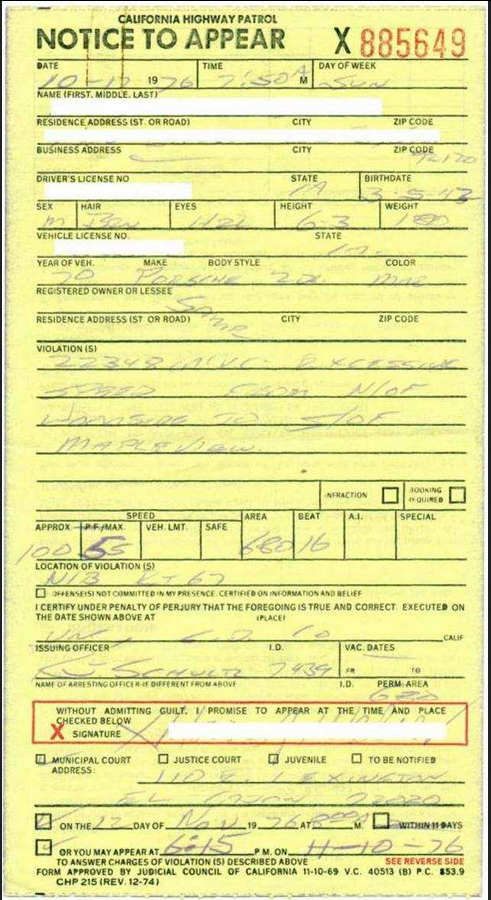

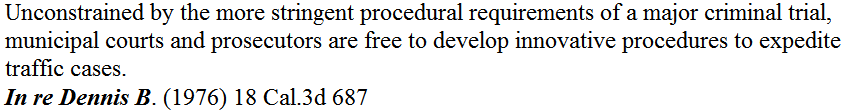

NOTICE

TO APPEAR

IS NOT

A COMPLAINT

IS NOT

A COMPLAINT

"Every

fact which, if controverted, plaintiff must prove to maintain his

action must be stated in the complaint."

Jerome

v.

Stebbins (1859), 14 C. 457;

Green v.

Palmer (1860), 15 C. 411, 76 Am. Sec. 492;

Johnson

v.

Santa Clara County (1865), 28 C. 545.

"The complaint, on its face, must show that the

plaintiff has the better right."

Rogers

v.

Shannon (1877), 52 C. 99

[4]

A plaintiff is required to set forth in his complaint the essential

facts of his case with reasonable precision and with sufficient clarity

and particularity that the defendant may be apprised of the nature,

source and extent of his cause of action. (Dunn v. Dufficy, 194 Cal.

383, 391 [228 P. 1029]; Rannard v. Lockheed Aircraft Corp., 26 Cal.2d

149, 156 [157 P.2d 1]; Goldstein v. Healy, 187 Cal. 206, 210 [201 P.

462]; Miller v. Pacific Constructors, Inc., 68 Cal.App.2d 529, 539 [157

P.2d 57].)

Metzenbaum

v.

Metzenbaum, 86 Cal.App.2d 750

[Civ. No. 16288. Second Dist., Div. Two. July 14,

1948.]

"Complaint,

to be sufficient, must contain a statement of facts which, without the

aid of other facts not stated shows a complete cause of action."

Going v.

Dinwiddie (1890), 86 C. 633, 25 P. 129.

"Pleadings should set forth facts, and not merely

the opinions of parties."

Snow v.

Halstead (1851), 1 C. 359.

[2]

(2) In pleading, the essential facts upon which a determination of the

controversy depends should be stated with clearness and precision so

that nothing is left to surmise. (Philbrook v. Randall, 195 Cal 95, 103

[231 P. 739].)

[3] (3) Mere recitals, references to or

allegations of material facts which are left to surmise are subject to

a special [98 Cal.App.2d 444] demurrer for uncertainty. (Corum v.

Hartford Acc. & Ind. Co., 67 Cal.App.2d 891, 894 [155 P.2d

710].)

[4]

Applying the foregoing rules to the facts of the instant case it is

evident that the trial court's orders and judgments must be sustained.

The orders sustaining the demurrers were general in their terms and

therefore under rule (1) supra, if properly taken on any ground stated

therein must be affirmed.

Bernstein

v.

Piller, 98 Cal.App.2d 441

[Civ. No. 17607. Second Dist., Div. Two. July 13,

1950.]

"A

complaint must contain a statement of facts showing the jurisdiction of

the court, ownership of a right by plaintiff, violation of that right

by the defendant, injury resulting to plaintiff by such violation,

justification for equitable relief where that is sought, and a demand

for relief."

Pierce

v.

Wagner, 134 F.2d. 958.

"Essential

facts on which legal points in controversy depend, should be pleaded

clearly and precisely, so that nothing is left for court to surmise."

Gates v.

Lane

(1872), 44 C. 392.

"The

test of the materiality of an averment in a pleading is this: Could the

averment be stricken from the pleading without leaving it insufficient?"

Whitwell

v.

Thomas (1858), 9 C. 499.

"In

pleading, the essential facts on which a determination of the

controversy depends should be stated with clearness and precision so

that nothing is left to surmise."

Bernstein

v.

Fuller (1950), 98 C.A.2d 441, 220 P.2d 558.

"The

"facts" which the court is to find and the "facts" which a pleader is

to state lie in the same plane - that is, in both connections, "facts"

are to be stated according to their legal effect."

Hihn v.

Peck

(1866), 30 C. 280.

"In general, matters of substance must be alleged

in direct terms, and not by way of recital or reference."

Silvers

v.

Grossman (1920), 183 C. 693, 192 P. 534; Reid v. Kerr

(1923), 64 C.A. 117, 220 P. 688.

"A fact which constitutes an essential element of

a cause of action cannot be left to inference."

Roberts

v.

Roberts, 81 C.A.2d 871, 185 P.2d 381.

"Material facts must be alleged directly and not

by way of recital."

Vilardo

v.

Sacramento County (1942), 54 C.A.2d 413, 129 P.2d 165.

"Material allegations must be distinctly stated

in complaint."

Goland

v.

Peter Nolan & Co. (1934), 33 P.2d 688, subsequent

opinion 38 P.2d 783, 2 C.2d 96.

"Matters of substance must be presented by direct

averment and not by way of recital."

Stefani

v.

Southern Pacific Co. (1932), 119 C.A. 69, 5 P.2d 946.

"A pleading which leaves essential facts to

inference or argument is bad."

Ahlers.

v.

Smiley (1909), 11 C.A.343, 104 P. 997.

"The

forms alone of the several actions have been abolished by the

statute. The substantial allegations of the complaint in a

given

case must be the same under our practice act as at common law."

Miller

v. Van

Tassel (1864), 24 C. 459.

"A pleading cannot be aided by reason of facts

not averred."

San

Diego

County v. Utt (1916), 173 C. 554, 160 P. 657.

"[2]

While the complaint should be liberally construed, with a view to

substantial justice between the parties (Code Civ. Proc., sec. 452),

that rule "does not, however, permit the insertion, by construction, of

averments which are neither directly made nor within the fair import of

those which are set forth. On the contrary, facts necessary to a cause

of action but not alleged must be taken as having no existence." (21

Cal.Jur. 54; Feldesman v. McGovern, (1941) 44 Cal.App.2d 566, 571 [112

P.2d 645]; Estrin v. Superior Court, (1939) 14 Cal.2d 670, 677 [96 P.2d

340].) ."

Frace v.

Long

Beach City High School Dist. (1943), 137 P.2d 60, 58

C.A.2d 566

"A fact necessary to pleader's cause of action,

if not pleaded, must be taken as having no existence."

Feldesman

v.

McGovern (1941), 44 C.A.2d 566.

"When

pleading is silent as to material dates, or does not clearly state

facts relied on, it must be presumed that statement thereof would

weaken pleader's case."

Whittemore

v.

Davis (1931), 112 C.A. 702, 297 P. 640.

"Material matters in pleadings must be distinctly

stated in ordinary and concise language."

Brown v.

Sweet

(1928), 95 C.A. 117, 272 P. 614.

"Facts

contained in public records should be alleged in pleading when they

constitute necessary elements of good cause of action."

Gray v.

White

(1935), 5 C.A.2d 463, 43 P.2d 318.

"When facts are available from public records, it

is ordinarily improper to allege such facts on mere information and

belief."

People

v.

Birch Securities Co. (1948), 196 P.2d 143, 86 C.A.2d 703,

cert. denied

Birch

Securities Co. v. People of State of California, 69 S.Ct.

745, 336 U.S. 936, 93 L.Ed. 1095.

Traffic

experts and the public agree that traffic law enforcement is "criminal"

only in a limited procedural sense. The public and

the

legal system recognize that unsafe driving is a serious social problem,

and the role of law enforcement is to promote traffic safety and

improve driver behavior. For the most part, trials

of

traffic infractions involve no complex problems of law or fact. fn.

3 Attorneys rarely appear in infraction cases for

the

simple reason that the stakes are not worth the

cost. For a

judge who has no special interest in the subject, traffic court is

characterized by the pressure of high volume and the monotony of

repetition. fn. 4 In a large metropolitan court,

where

judicial assignments are influenced by seniority, traffic cases are

assigned to the newest judges on the court, or to commissioners.

In

some jurisdictions traffic infractions have been removed from the

judicial branch and handled by administrative hearing officers attached

to the executive agency which issues operator's

licenses.

In 1975 the California Legislature requested the California Department

of Motor Vehicles to undertake a study to determine the feasibility of

adjudicating minor traffic cases administratively in this state. (Sen.

Con. Res. No. 40, Stats. 1975, Res. ch. 86.) The

department

did conduct such a study and in April 1976 published its report which

concluded, among other things, that administrative adjudication by

legally trained hearing officers "would stabilize and enhance the

quality and efficiency of infraction processing and adjudication." (1

Cal. Dept. of Motor Vehicles: Administrative Adjudication of Traffic

Offenses in Cal. p. 21.)

To avoid a

conflict with the separation of powers requirement of the California

Constitution, the report contemplated that the decisions of the [82

Cal.App.3d 53] administrative hearing officers would be subject to

judicial review in the superior court through a proceeding in mandamus

under Code of Civil Procedure, section 1094.5. (Id, p.

142.) As a practical matter, such a review would be

unavailable to most individuals who were aggrieved by an administrative

decision. Mandate proceedings in the superior court

(unlike

traffic trials) are relatively complex and expensive, and are rarely

attempted without the assistance of an attorney.

Many

persons would be unable and most would be unwilling to incur the

expense of that kind of litigation to escape the administratively

imposed sanction. Thus for all practical purposes,

administrative adjudication would mean a final decision by a person who

was not a judicial officer at all.

The

California Legislature thus far has kept traffic adjudication within

the judicial branch but with expanded use of subordinate judicial

officers.

...the trial of traffic

infraction cases calls for the talents of a person who understands the

special societal function of traffic law enforcement, who is committed

to its educational objective and who has the personal capability of

dealing with people expeditiously, fairly, and in good

spirit.

Regardless

of what the collateral consequences of a traffic conviction may be, our

concern should focus upon the accuracy of the adjudicatory system in

determining which persons charged with violations are in fact

violators. In the context of our present inquiry,

the

crucial question is whether the conviction of the innocent is more

likely to occur in an infraction trial before a commissioner than

before a judge.

People

v.

Lucas (1978) 82 Cal.App.3d 47

Moreover,

the state's substantial interest in maintaining the summary nature of

minor motor vehicle violation proceedings would be impaired by

requiring the prosecution to ascertain for each infraction the

possibility of further criminal proceedings. The

chief

reason for classifying some prohibited acts as infractions is to

facilitate their swift disposition. (People v. Battle (1975) 50

Cal.App.3d Supp. 1, 7 [123 Cal.Rptr. 636].) Unconstrained by

the

more stringent procedural requirements of a major criminal trial,

municipal courts and prosecutors are free to develop innovative

procedures to expedite traffic cases.

In re

Dennis B.,

18 Cal.3d 687

[S.F. No. 23453. Supreme Court of California.

December 28, 1976.]

-

INNOVATIVE PROCEDURES

-

WE'RE GONNA MAKE IT REAL EASY FOR YOU!

GET IT?!

WE'RE GONNA MAKE IT REAL EASY FOR YOU!

GET IT?!

(Actual roadside court. Inglewood,

California, 1926)

(Actual roadside court. Inglewood,

California, 1926) OFFICER:

Sir this is where we accept pleas for violations of the Vehicle Code.

DEFENDANT:

Well you mean alleged violations of the Vehicle Code is that

right? Otherwise why would you need a plea if

you’ve

already determined I’m guilty as alleged?

OFFICER: Sir are you trying to be a

smart ass?

DEFENDANT: No.

OFFICER: Ok then what’s your

plea?

DEFENDANT: Well is the

alleged violation a crime?

OFFICER: It’s an offense sir

and this is where we accept pleas for offenses of the Vehicle Code.

DEFENDANT:

Again officer, you mean alleged offense right because if it’s already

concluded I committed an offense then why would you need a plea?

OFFICER: Are you

trying to be a smart ass?

DEFENDANT: No.

OFFICER: So what’s your plea?

DEFENDANT: Is the alleged

offense a crime?

OFFICER: Sir you’ve been

charged with violating the Vehicle Code now what’s your plea?

DEFENDANT:

Again officer, and I mean no disrespect but you mean alleged violation

right because if it’s already been determined, rather than just

alleged, that I violated anything then you wouldn’t need a plea right?

OFFICER:

Yeah that’s right but remember this is 1926 and all we have are

misdemeanors and felonies but if it was after 1968 then it would be an

infraction, but it’s not after 1968 so it’s a misdemeanor which is a

crime, so yeah, you’ve been accused of a crime, now what’s your plea?

The

primary purpose of a constitution is to place limitations

upon the legislative authority as well as upon the powers of its

co-ordinate branches of government.

Allen v.

State Board of Equalization (1941) 43 Cal.App. 2d 90

Obviously,

administrative agencies, like police officers must obey the

Constitution and may not deprive persons of constitutional rights.

Southern

Pac.

Transportation Co. v. Public Utilities Com., 18 Cal.3d 308

[S.F. No. 23217. Supreme Court of California.

November 23, 1976.]

“The

state constitution is the supreme law of the state,...”. “If

there is

any difference in meaning between the constitution and a statute, the

constitution must prevail,...”.

13

Cal.Jur.3d (Rev) §4, Part 1, p. 25

THERE IS

NO PROSECUTOR BUT THERE IS AN ARRAIGNMENT

THERE IS

NO PROSECUTOR BUT THERE IS AN ARRAIGNMENT

NEITHER THE PEOPLE NOR THEIR ATTORNEY APPEARS

NEITHER THE PEOPLE NOR THEIR ATTORNEY APPEARS

ONLY THE

ATTORNEY GENERAL OR

DISTRICT ATTORNEY ARE

ONLY THE

ATTORNEY GENERAL OR

DISTRICT ATTORNEY ARE

THE

DISTRICT ATTORNEY HAS THE PREROGATIVE TO PROCECUTE AN ALLEGED CRIME

THE

DISTRICT ATTORNEY HAS THE PREROGATIVE TO PROCECUTE AN ALLEGED CRIME

THE

DISTRICT ATTORNEY IS NOT REQUIRED TO PROSECUTE AN ALLEGED CRIME

THE

DISTRICT ATTORNEY IS NOT REQUIRED TO PROSECUTE AN ALLEGED CRIME