All Are Presumed To Know The Law!

[2] The

people of the State of California are supreme and have the

undoubted right to protect themselves and to preserve the form of

government...

Steiner

v. Darby (1948) 88 Cal.App.2d 481

CALIFORNIA GOVERNMENT CODE

54950 DECLARATION OF LEGISLATIVE PURPOSE.

"In enacting this chapter, the Legislature finds and declares that the

public commissions, boards and councils and the other public agencies

in this State exist to aid in the conduct of the people's

business. It is the intent of the law that their actions be

taken openly and that their deliberations be conducted openly.

The

people of this State do not yield their sovereignty to the agencies

which serve them. The people, in delegating authority, do not

give their public servants the right to decide what is good for the

people to know and what is not good for them to know. The

people insist on remaining informed so that they may retain control

over the instruments they have created".

CONSTITUTION OF

THE STATE OF CALIFORNIA

1849

Art. I

Sec. 2.

All political

power is inherent in the people. Government is instituted for the

protection, security and benefit of the people; and

they have the right to alter or reform the same, whenever the public good may require it.

The "GOVERNMENT" belongs to the

People, not the People's employees.

"Municipal authorities, as

trustees for the public, ...

Pittsford v. City of

Los Angeles (1942) 50 Cal.App.2d 25

"Municipal authorities, as

trustees for the public, ...

Pittsford v. City of

Los Angeles (1942) 50 Cal.App.2d 25

THANKFULLY!

THANKFULLY!

The

“Flesch Index”, this is an objective method of measuring the

readability of English text. This index measures the level of

understanding necessary for someone to comprehend the written English

language. The average newspaper is written at a Flesch index

of 7.

The average high school graduate reads and understands at a

level of

10. The average law school grad reads and understands at a level

of

15. The Internal Revenue Code ranks a 31, with some specific

provisions as high as an astounding 55. To further confuse the

issue,

the words used in law have specific legal definitions that are very

different from the common English definitions.

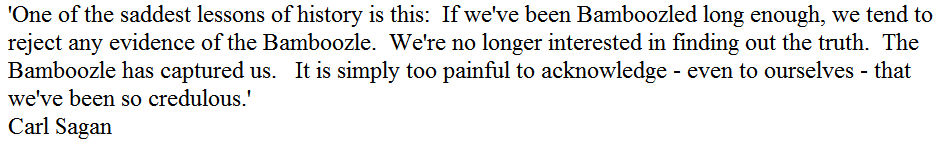

If

the laws that we are to obey, are written at a level that an individual

of average intelligence cannot understand, then perhaps we have reason

to be suspect of the writers' motives. The IRS code is at

31, people

in this country cannot understand at this level, this is more than

twice the level of a law school graduate! What that means is that

even

when you hire a lawyer, he will have trouble interpreting what it

means. The real danger here is, people who are considered

“experts”

on a subject that is beyond your comprehension can mislead and

bamboozle you at will!. How many people have the time, energy,

and

ability to go into a law library and piece this puzzle together?

It

seems that by making the law so difficult to read, the State

Legislature and Congress has effectively removed our access to it.

The

Legislature is presumed to know existing law when it enacts a new

statute, including the existing state of the common law. (See, e.g.,

Keeler v. Superior Court (1970) 2 Cal.3d 619 , 625 [87

Cal.Rptr. 481,

470 P.2d 617, 40 A.L.R.3d 420] ["It will be presumed, of course, that

in enacting a statute the Legislature was familiar with the relevant

rules of the common law."]; People v. Welch (1971) 20

Cal.App.3d 997,

1002 [98 Cal.Rptr. 113] ["It also [67 Cal.App.4th 1501] may be

assumed

that the 1951 amendments were enacted by a Legislature familiar with

its previous acts, existing judicial decisions construing the same, and

the common law rules."]; Schmidt v. Southern Cal. Rapid Transit

Dist.

(1993) 14 Cal.App.4th 23 , 27 [17 Cal.Rptr.2d 340] ["[I]t is

assumed

that the Legislature has existing laws in mind at the time that it

enacts a new statute. (Estate of McDill (1975) 14 Cal.3d 831 ,

837

[122 Cal.Rptr. 754, 537 P.2d 874].)"].)

Arthur

Andersen v. Superior Court (Quackenbush) (1998) 67 Cal.App.4th

1481 , 79 Cal.Rptr.2d 879

[No. B118547. Second Dist., Div. Two. Nov 24, 1998.]

Persons

dealing with a public agency are presumed to know the law and are bound

at their peril to ascertain and follow those procedures necessary to

enter into a binding contract. (See Miller v. McKinnon, supra, 20

Cal.2d at p. 89; Bear River etc. Corp. v. County of Placer (1953) 118

Cal.App.2d 684 , 690 [258 P.2d 543].)

SEYMOUR

v. STATE OF CALIFORNIA, 156 Cal.App.3d 200

[Civ. No. 22606. Court of Appeals of California, Third

Appellate District. March 9, 1984.]

In

Pisani v. Martini (1933) 132 Cal.App. 269, 274 [217 Cal.App.2d

231]

[22 P.2d 804], the court stated: "It [the jury] is not presumed

to know

the law, and if in the absence of instructions it assumes to possess

such knowledge, any attempt to apply it to the facts of the case

constitutes a violation of its duty."

Smith v.

Wemmer , 217 Cal.App.2d 226

[Civ. No. 20817. First Dist., Div. Two. June 17, 1963.]

"Everyone

is presumed to know the law. And all applicable laws in

existence

when an agreement is made necessarily enter into it and form a part of

it as fully as if they were expressly referred to and incorporated in

its terms." (6 Cal.Jur. 310, § 186; Brown v. Ferdon, 5 Cal.2d 226

[54

P.2d 712]; Chapman v. Jocelyn, 182 Cal. 294 [187 P. 962]; Long v.

Newman, 10 Cal.App. 430 [102 P. 534].)

The contracting parties were, therefore, presumed to know all

existing laws...

Robertson

v. Dodson, 54 Cal.App.2d 661

[Civ. No. 12069. First Dist., Div. One. Oct. 2, 1942.]

It may be that citizens must be presumed to know the law.

(See 1 Witkin, Cal. Crimes (1963) § 148, p. 141.)

People

v. Carr (1988) 204 Cal.App.3d 774 , 251 Cal.Rptr. 458

[No. D005459. Court of Appeals of California, Fourth

Appellate District, Division One. September 16, 1988.]

...the

trial court apparently concluded that a police officer is presumed to

know the law relative to the proper procedures to be followed in

effecting a lawful eviction. Even if we assume that a

police officer

is presumed to know the law relative to the eviction of tenants for

nonpayment of rent,...

People

v. Superior Court (1970) 3 Cal.App.3d 648 , 83 Cal.Rptr. 732

[Civ. No. 34858. Court of Appeals of California, Second

Appellate District, Division Two. January 20, 1970.]

...all persons are presumed to know the law including that

which prohibits causing injury or death to another.

People

v. Maynarich, 83 Cal.App.3d 476

[Crim. No. 31052. Second Dist., Div. Five. July 31, 1978.]

...for all persons are presumed to know the law including

that which prohibits causing injury or death to another.

The

court in Poddar noted (p. 758): "The effect, ... which a diminished

capacity bears on malice in a second degree murder-implied malice case

is relevant to two questions: First, was the accused because of a

diminished capacity unaware of a duty to act within the law?

A person

is, of course, presumed to know the law which prohibits injuring

another. Second, even assuming that the accused was aware of

this duty

to act within the law, was he, because of a diminished capacity, unable

to act in accordance with that duty? [Citations; fn. omitted.]

If it is

established that an accused, because he suffered a diminished capacity,

was unaware of or unable to act in accordance with the law, malice

could not properly be found and the maximum offense for which he could

be convicted would be voluntary manslaughter." Thus malice as

the

Poddar court noted is to be properly implied when the killing resulted

from an accident involving a high degree of probability of death and is

accompanied by the requisite mental element. (Id, at p. 759.)

Poddar

fashioned that three-pronged inquiry as the proper procedure requisite

to a finding of malice aforethought. "First, was the act or acts done

for a base, antisocial purpose? Second, was the accused aware of

the

duty imposed upon him not to commit acts which involve the risk of

grave injury or death? Third, if so, did he act despite that

awareness?

The first determination is expressly required in accordance with

the

definition of implied malice, and the second and third determinations

are required relative to the question of 'wanton disregard' also in

accordance with the definition of implied malice." (Id, at pp. 759-760.)

PEOPLE

v. ODOM, 108 Cal.App.3d 100

[Crim. No. 11307. Court of Appeals of California, Fourth

Appellate District, Division One. July 11, 1980.]

"Everyone

is presumed to know the law" (Boehm v. Spreckels, 183 Cal. 239, 245

[191 P. 5]), and defendants herein, who, in the [253 Cal.App.2d

968]

disseminated advertising materials, held themselves out to the public

as experts in the law of trusts, taxation, and probate, are charged

with knowledge of the aforementioned law applicable to such trusts.

Even were defendants not charged with actual knowledge of the

untrue or

misleading nature of the statements relating to the legal consequences

of pure trusts, they, by the exercise of reasonable care, should have

known that the statements were untrue or misleading. The

statements are

made in an absolute, unqualified, and positive manner, and it has been

said (Lerner v. Riverside Citrus Assn., 115 Cal.App.2d 544 , 547

[252

P.2d 744]) that if a person "makes such an absolute, unqualified and

positive statement as implies knowledge on his part, when in fact he

has no knowledge whether his assertion is true or false, and his

statement proves to be false, he is as culpable as if he had wilfully

asserted that to be true which he knew to be false. ..."

People

ex rel. Mosk v. Lynam , 253 Cal.App.2d 959

[Civ. No. 31452. Second Dist., Div. One. Aug. 29, 1967.]

[5]

The guarantee of due process of law includes the requirement of

a

reasonable degree of certainty in legislation. (People v. Superior

Court (Caswell) (1988) 46 Cal.3d 381, 389 [250 Cal.Rptr. 515, 758 P.2d

1046].) To withstand a vagueness challenge, "a statute must be

sufficiently definite to provide adequate notice of the conduct

proscribed. '[A] statute which either forbids or requires the doing of

an act in terms so vague that men of common intelligence must

necessarily guess at its meaning and differ as to its application,

violates the first essential of due process of law. [Citations.]'

[Citations.]" fn. 16 (Caswell, supra, 46 Cal.3d at p. 389.) In

considering whether a legislative proscription is sufficiently clear to

satisfy the requirements of fair notice, we consider not only the

language of the challenged statute, but also its legislative history.

(Walker v. Superior Court (1988) 47 Cal.3d 112, 143 [253 Cal.Rptr. 1,

763 P.2d 852].) "We thus require citizens to apprise themselves not

only of statutory language but also of legislative history ... and

underlying legislative purposes [citation]. [Citation.]" (Ibid.)

People

v. Morse (1993) 21 Cal.App.4th 259 , 25 Cal.Rptr.2d 816

[Nos. A058935, A060033. First Dist., Div. Three. Dec 22,

1993.]

[19]

In considering whether a legislative proscription is

sufficiently clear

to satisfy the requirements of fair notice, "we look first to the

language of the statute, then to its legislative history, and finally

to California decisions construing the statutory language." (Pryor v.

Municipal Court (1979) 25 Cal.3d 238, 246 [158 Cal.Rptr. 330, 599 P.2d

636]; People v. Mirmirani (1981) 30 Cal.3d 375, 383 [178 Cal.Rptr. 792,

636 P.2d 1130].) We thus require citizens to apprise themselves not

only of statutory language but also of legislative history, subsequent

judicial construction, and underlying legislative purposes (People v.

Grubb (1965) 63 Cal.2d 614, 620 [47 Cal.Rptr. 772, 408 P.2d 100]). (See

generally Amsterdam, The Void-For-Vagueness Doctrine in the Supreme

Court (1960) 109 U. Pa. L.Rev. 67.) These principles express the strong

presumption that legislative enactments "must be upheld unless their

unconstitutionality clearly, positively, and unmistakably appears.

[Citations.] A statute should be sufficiently certain so that a

person

may know what is prohibited thereby and what may be done without

violating its provisions, but it cannot be held void for uncertainty if

any reasonable and practical construction can be given to its

language." (Lockheed Aircraft Corp. v. Superior Court (1946) 28 Cal.2d

481, 484 [171 P.2d 21, 166 A.L.R. 701], citations omitted.)

Walker

v. Superior Court (1988) 47 Cal.3d 112

[S.F. No. 24996. Supreme Court of California. November 10,

1988.]

Officer Young ordered Clement’s car towed because he believed

the car was parked in a public lot in violation of the statute.

Even

if the officer is not expected to know the law of all 50 states, surely

he is expected to know the California Vehicle Code...

CLEMENT

v. J & E SERVICE INC., No. 05-56692, March 11, 2008,

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT

Even

if the officer is not expected to know the law of all 50 states, surely

he is expected to know the California Vehicle Code,...

THE

PEOPLE v. JESUS SANTOS SANCHEZ REYES (2011) 196 Cal.App.4th 856

UNITED STATES ATTORNEY GENERAL

LORETTA LYNCH

"...look at the statute..."

UNITED STATES ATTORNEY GENERAL

LORETTA LYNCH

"...look at the statute..."

House Judiciary Committee, July 12, 2016