The information that follows originates from State

and federal government sources. What follows is

FOUNDATIONAL to the legal system in America and every state that

comprises America.

JUDGES ARE MANDATED OR OBLIGATED TO TAKE JUDICIAL NOTICE OF THE FOLLWING AND RULE IN ACCORDANCE WITH IT.

CALIFORNIA EVIDENCE CODE

SECTION 450-460

450. Judicial notice may not be taken of any matter unless authorized or required by law.

451. Judicial notice shall be taken of the following:

(a) The decisional, constitutional, and public statutory law of this state and of the United States and the provisions of any charter described in Section 3, 4, or 5 of Article XI of the California Constitution.

(b) Any matter made a

subject of judicial notice by Section 11343.6, 11344.6, or 18576 of the

Government Code or by Section 1507 of Title 44 of the United States

Code.

(c) Rules of

professional conduct for members of the bar adopted pursuant to Section

6076 of the Business and Professions Code and rules of practice and

procedure for the courts of this state adopted by the Judicial Council.

(d) Rules of

pleading, practice, and procedure prescribed by the United States

Supreme Court, such as the Rules of the United States Supreme Court,

the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, the Federal Rules of Criminal

Procedure, the Admiralty Rules, the Rules of the Court of Claims, the

Rules of the Customs Court, and the General Orders and Forms in

Bankruptcy.

(e) The true signification of all English words and phrases and of all legal expressions.

(f) Facts and propositions of

generalized knowledge that are so universally known that they cannot

reasonably be the subject of dispute.

CANONS OF JUDICIAL ETHICS

- ALL JUDGES SHALL COMPLY WITH THIS CODE -

CALIFORNIA GOVERNMENT CODE sec. 14: "Shall" is mandatory...

CALIFORNIA WORDS,

PHRASES AND MAXIMS

(As defined in the codes and cases)

FILL

TO

MOOT

1960

Bancroft – Whitney company

San Francisco

p. 676

MAY

“Shall” means “must,” while “may” means “to have power.”

National Auto and Casualty Insurance Company v. Garrison (1946) 76 Cal. App. 2d 415

p. 714

MINISTERIAL

Where a statute requires an officer to do a prescribed act upon a prescribed contingency, his functions are “ministerial”.

Drummey v. State Board of Funeral Directors v. Embalmers (1939) 13 Cal.2d 75

A “ministerial act” is one which a public officer is required to

perform in a prescribed manner in obedience to the mandate of legal

authority and without regard to his own judgment or opinion concerning

the propriety or impropriety of the act to be performed, or when given

a state of facts exist.

Williams v. Stockton (1925) 195 Cal. 743

A “ministerial act” is one unqualified of the required of a public

officer, though the manner of performance may be discretionary.

Any duty is “ministerial” which unqualifiedly requires the doing of a

certain thing; to the extent that its performance is unqualifiedly

required, is not discretionary, even though the manner of its

performance may be discretionary.

Ham v. Los Angeles County (1920) 46 Cal.App. 148

A “ministerial duty” is one in respect to which nothing is left to the

discretion; it is a simple, definite duty, arising under circumstances

admitted or proved to exist, and imposed by law.

Sullivan v. Shanklin (1883) 63 Cal. 247

p. 718 - 719

MISBRANDED

While the term “misrepresent” was not used in the California Economic

Poison Act of 1921 §2, the term “misbranded” which was used in the

title of the act included that of misrepresentation; and the evident

intent of the legislature was to prohibit the adulteration, misbranding

and misrepresentation in the use or sale of economic poisons.

Gregory v. Hecke (1925) 73 Cal.App. 268

Packaged and labeled candy that is stale and altered in flavor,

appearance and chemical composition is “adulterated” in the sense that

it is decomposed, and in the sense that it’s damaged or inferiority has

been concealed, and, where the labels do not indicate such condition of

the product, such candy is “misbranded” within the meaning of H & S

C §26490.

People v. 748 Cases of Life Saver Candy Drops (1949) 94 Cal.App.2d 599

p. 719

MISCARRIAGE

It would be a “miscarriage of justice” to refuse a new trial where a

judge was of the opinion that the reasonable doubt rule had not been

complied with, or that an element of the offense had not been

established as required by that rule.

People v. Nelson (1940) 36 Cal.App.2d 515

If a defense is permissible in a particular case, refusal to receive

evidence in its support constitutes a “miscarriage of justice” of such

a character as to be in violation of Constitution Article VI §4 ½.

Southern California Homebuilders v. Young (1920) 45 Cal.App. 679

The phrase “miscarriage of justice,” within the meaning of Constitution

article VI §4 ½, does not simply mean that a guilty man has escaped, or

that an innocent man has been convicted; is equally applicable to cases

where the acquittal or the conviction has resulted from some form of

trial in which the essential rights of the people or of the defendant

were disregarded or denied.

People v. Weatherford (1945) 27 Cal.2d 401

People v Wilson (1913) 23 Cal.App. 513

People v. Adams (1926 76 Cal.App. 178

People v. Mellus (1933) 134 Cal.App.219

People v. Gilliland (1940) 39 Cal.App. 2d 250

People v. Cowan (1941) 44 Cal.App.2d 155

People v. Rodriguez (1943) 58 Cal.App.2d 415

People v. Smittcamp (1945) 70 Cal.App.2d 741

People v. Hooper (1949) 92 Cal.App.2d 524

People v. Geibel (1949) 93 Cal.App.2d 147

p. 691 - 692

MENACE

Under CC §1570 “menace” consists, among other things, of a threat of

“injury to the character of” the persons mentioned in §1569 defining

duress; and it is well-settled generally that the threat of arrest on a

criminal charge in aid of the collection of debt constitutes “menace,”

which in criminal law is extortion and amounts to a felony, and civil

law warrants rescission and may be set up in defense of an action on

debt.

Bridges v. Ruggles (1927) 202 Cal. 326

A threat of arrest and imprisonment, made from lawful purposes,

constitutes “menace” within the meaning of CC §1570, defining menace as

a threat of duress or of a threat of injury to the character of a

person.

Morrill v. Nightingale (1892) 93 Cal. 452

Miller v. Walden (1942) 53 Cal.App.2d 353

The threat which is necessary to constitute “menace” must be more than

some statement or act from which a guilty person becomes apprehensive

the prosecution – it is the threat and not the apprehension which makes

out the “menace” and that threat must be in an unlawful and invalid one.

Miller v. Walden (1942) 53 Cal.App.2d 353

An agreement obtained under threat of criminal prosecution is void even

if amount agreed to be paid is due, because of the criminal prosecution

as a means of collecting a debt is against public policy ;such threats

constitute “menace” destructive of free consent.

Shasta Water Company v. Croke (1954) 128 Cal.App.2d 760

P. 741

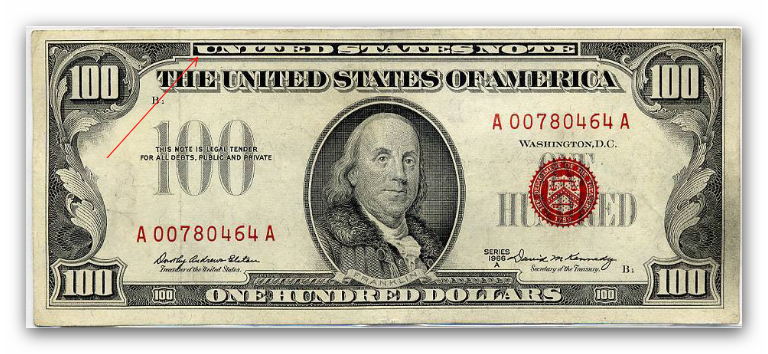

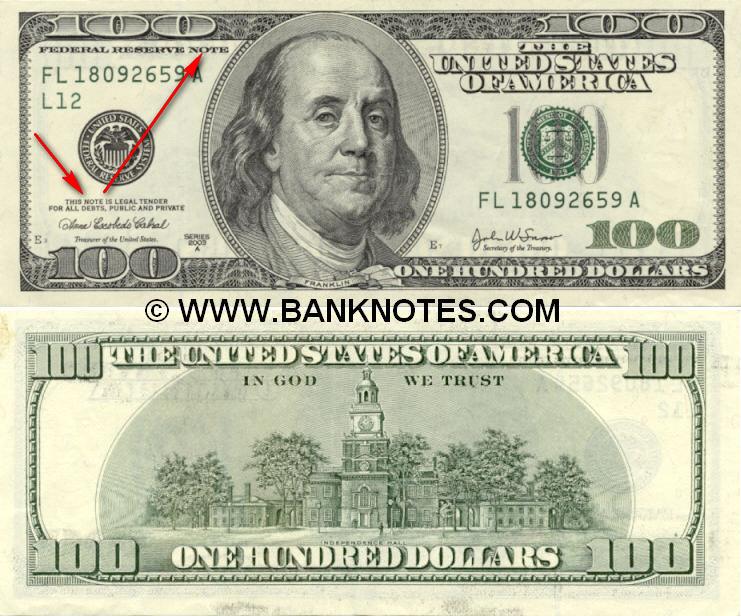

MONEY

By the laws of the land in 1864, the country was furnished with three kinds of money – gold, silver, and United States notes,

as a medium of exchange; “money” made by the coinage of gold or silver,

was a legal tender, as prescribed by law, in the discharge of

obligations, which were to be satisfied by the payment of “money” in

general terms.

Carpentier v. Atherton (1864) 25 Cal. 404

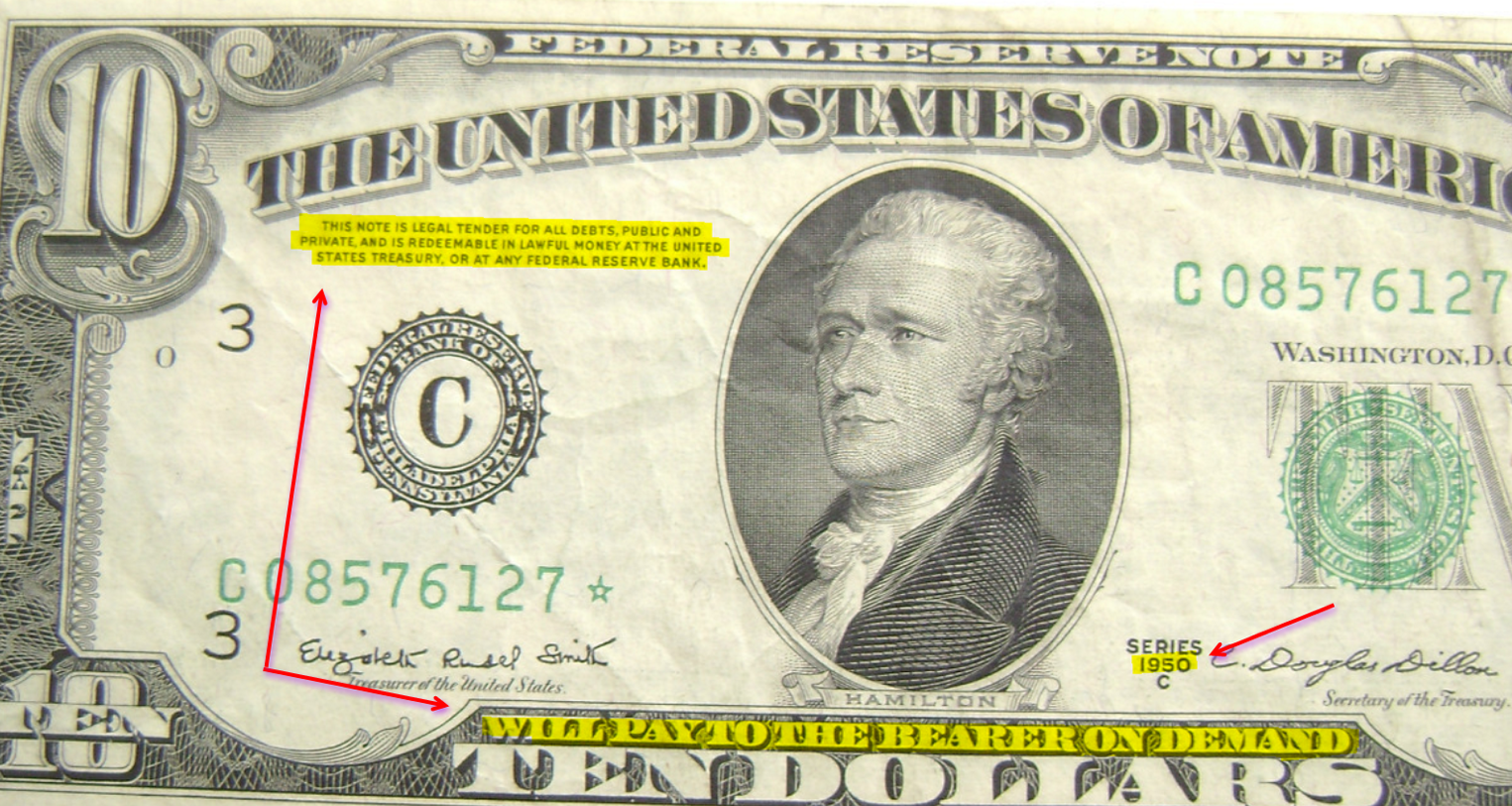

FEDERAL RESERVE NOTES ARE NOT MONEY!

FEDERAL RESERVE NOTES ARE I.O.U.s!

YOU CAN NOT "PAY" FOR ANYTHING WITH AN I.O.U!

THIS IS MONEY ACCORDING TO THE LEGAL DEFINITION:

THIS IS NOT MONEY ACCORDING TO THE LEGAL DEFINITION:

MONEY.

In usual and ordinary acceptation it means gold, silver, or paper money

used as circulating medium of exchange, and does not embrace notes,

bonds, evidences of debt, or other personal or real estate. Lane

v. Railey, 280 Ky. 319, 133 S.W.2d 74, 79, 81.

BLACK’S LAW DICTIONARY, 4th Edtiton, p. 1157.

THAT USED TO

BE PRINTED ON FEDERAL RESERVE NOTES IN 1950. THEN THE

FEDERAL RESERVE DECIDED THEY WOULD NOT CONVERT THIER IOUs TO ACTUAL

MONEY ANY MORE.

CALIFORNIA WORDS,

PHRASES and MAXIMS

(As defined in the codes and cases)

MORAL

TO

RESIDE

BANCROFT - WHITNEY COMPANY

San Francisco

1960

“Municipal” pertains to a city or corporation having the right of

administering local government - as “municipal” rights, “municipal”

officers.

In re Werner (1900) 129 Cal. 567

Randolph v. Stanislaus County (1919) 44 Cal.App. 322

The term “municipal,” as commonly used, is appropriately applied to all

corporations governmental functions, either general or special.

Merchants National Bank v. Escondido Irrigation District (1904) 144 Cal. 329

Siler v. Industrial Acc. Com. (1957) 150 Cal.App.2d 157

“Municipal” means an inferior power or jurisdiction rather than state jurisdiction.

Clements v. Bechtel (T.R.) Co. (1954) 43 Cal.2d 227

CALIFORNIA WORDS,

PHRASES AND MAXIMS

BANCROFT – WHITNEY COMPANY

1960

RESIDENCE

TO

ZONING

~~~~~~~~~~~~

p. 63

SALE; TAX:

The “sales tax” imposed by the retail sales tax act is an excise tax on the retailer and not on the consumer.

de Aryan v. Akers (1938) 12 Cal.2d 156

The “sales tax” and the “trucking tax” are excise and not property

taxes. Each is a well defined privilege tax: one for the

privilege of selling tangible personal property retail and the other

for the privilege of using the public highways for hauling

services. Though each taxes measured by gross receipts,

separate and distinct privileges are involved. The

imposition of such taxes therefore presents no problem of double

taxation

Select Base Materials, Inc. v. State Board of Equalization (1959) 51 Cal.2d 640

A “sales tax” is an excise and privilege tax levied on a retailer for

the privilege of selling tangible personal property. The

law imposes the fixed rate of the tax on gross receipts and not on the

individual sale of tangible personal property. It is not a

tax on the sale or because of the sale but is an excise tax for the

privilege of conducting a retail business measured by the gross

receipts from sales. It has uniformly and consistently been

held that the sales tax is solely on the retailer and not on the

consumer. The relationship is between the retailer only and

the state; and is a direct obligation of the former. A

retailer may “pass on” tax to a buyer with the latter’s consent thereto

either expressly or impliedly given. In the absence of

either the express or implied consent of the buyer that he will assume

the burden of paying the tax, he is under no legal liability to do so.

Livingston Rock & Gravel Company v. De Salvo (1955) 136 Cal.App.2d 156

p. 160 - 161

SPECIAL; APPEARANCE:

p. 160 - 161

SPECIAL; APPEARANCE:

If the defendant by his appearance insist only upon the objection that

he is not in court for want of jurisdiction over his person and

confines his appearance for that purpose only, then he is made a

“special appearance,” but if he raises any other question, or asks any

relief which can only be granted upon the hypothesis that the court had

jurisdiction of his person, then he has made a general appearance.

Judson v. Superior Court (1942) 21 Cal.2d 11

Bank Of America National Trust and Savings Association v. Harrah (1952) 113 Cal. App. 2d 6 39

If a party appears in objects only to the consideration of the case or

any procedure in it because the court had not acquired jurisdiction of

the person of the defendant or a party, then the “appearance” is

special.

Judson v. Superior Court (1942) 21 Cal.2d 11,

Brock v. Fouchy (1946) 76 Cal.App.2d3 63,

Milstein v Ogden (1948) 84 Cal.App.2d2 29,

Proctor and Schwartz Inc. v. Superior Court (1950) 99 Cal.App.2d 376

An appearance made only for the purpose of moving to dismiss an action

on any one of the grounds specified in CCP §581a for lack of

prosecution is an “special appearance.”

Frohman v. Bonelli (1949) 91 Cal.App.2d 285

If the defendant, by his appearance, insist only upon the objection

that he is not in court for want of jurisdiction over the person, and

confines his appearance for the purpose only, then he has made a

“special appearance.”

Pease v. San Diego (1949) 93 Cal.App.2d 843

An objection, phrased in the language of the demurrer, on the ground

that the court had not acquired jurisdiction of the person of the

defendant is a “special appearance.”

Proctor and Schwartz Inc. v. Superior Court (1950) 99 Cal.App.2d 376

The test as to whether an appearance is “general” or “special” is, did

the party appear and object only to the consideration of the case or

any procedure in it because the court had not acquired jurisdiction of

the person of the defendant or party? If so, then the

appearances “special.” If, however, he appears and asked

for any relief which could be given only to a party in a pending case,

or which itself would be a regular proceeding in the case, it is a

“general” appearance regardless of how adroitly, carefully or directly

the appearance may be denominated or characterized as

special. The rule in this regard may be epitomized by

saying that if the defendant by his appearance insist only upon the

objection that he is not in court for want of jurisdiction over his

person and confines his appearance for that purpose only, then he has

made a special appearance, but if he raises any other question, or

assess any relief which can only be granted upon the hypothesis that

the court has jurisdiction of this person, then he is made a general

appearance.

Judson v. Superior Court (1942) 21 Cal.2d 11,

Armstrong v. Superior Court (1956) 144 Cal.App.2d 420

CALIFORNIA VEHICLE CODE

DIVISION 17. OFFENSES AND PROSECUTION

CHAPTER 2. PROCEDURE ON ARRESTS

Article 1. Arrests .................... 40300 - 40313

Lexicographers define the word "wait": "To rest patiently in

expectation: Remain inactive or stay in one place in anticipation

of an arrival or an event, or until the proper time comes for action."

-- Webster. Among the definitions by the same author of the

word "stop" we find: "To bring from motion to rest: Arrest the

course, progress, or movement."

Wixon v. Raisch Improv. Co. (April 19, 1928) 91 Cal. App. 129, Civ. No. 6073, Court of Appeal of California, First Appellate District, Division Two

stop - verb

6a: to arrest the progress or motion of : cause to halt

stopped the car

intransitive verb

2a: to cease to move on : HALT

3a: to break one's journey : STAY

"To bring from motion to rest: Arrest the course, progress, or movement."

noun

6a: a halt in a journey : STAY

halt - verb

transitive verb - to bring to a stop

https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/stop

STOP. Within a statute requiring a motorist striking a person with automobile to stop requires a definite cessation of movement

for a sufficient length of time for a person of ordinary powers of

observation to fully understand the surroundings of the accident. Moore

v. State, 140 Tex.Cr. R. 482, 145 S.W.2d 887, 888.

Black’s Law Dictionary, 4th Ed., 1951, p. 1588

STOPPAGE IN TRANSITU. The act by which the unpaid vendor of goods

stops their progress and resumes possession of them, while they are in

course of transit from him to the purchaser, and not yet actually

delivered to the latter.

Black’s Law Dictionary, 4th Ed., 1951, p. 1588, 1589

halt - noun: STOP

The car came to a halt.

Synonyms

Verb (1)

arrest

stop

https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/halt

BOULEVARD. A public

street which is usually of greater width than ordinary business

streets, and is given a park like appearance by reserving spaces at the

sides or center for shade trees, flowers, seats, and the like, and

ordinarily is not used for heavy teaming. It is usually set

apart for pleasure driving rather than general business purposes of an ordinary street. See Haller Sign Works v. Physical Culture Training School, 249 Ill. 436, 34 L.R.A. (N.S.) 989, 1002, 94 N.E. Rep. 920

Ballentine Law Dictionary, 2 nd Ed., 1948, p. 168

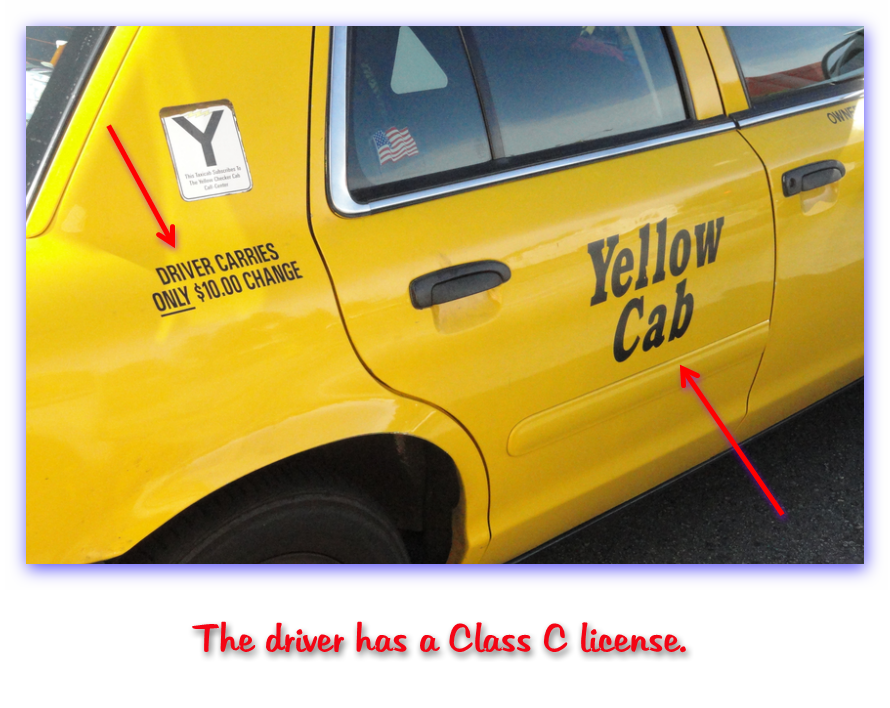

Driver - Webster's Unified Dictionary and Encyclopedia, International Illustrated Edition (1960)

One that drives; a chauffeur, coachmanm or the like;

Driver - Bouvier's Law Dictionary, 1856

One employed...

Driver - Black's Law Dictionary, 1st ed., 1891

One employed...

Driver - Black's Law Dictionary, 2nd ed., 1910

One employed...

Driver - Black's Law Dictionary, 3rd Ed, 1933

One employed...

Driver - Black's Law Dictionary 4th Ed., 1951

One employed...

Driver - Black's Law Dictionary, 6th Ed., 1991

A person actually doing driving,

whether employed by owner to drive or driving his own vehicle.

Driver - Dictionary of Occupational Titles, 1965, Volume 1, Definition of Titles

(dom. ser.) see CHAUFFEUR.

OPERATOR - (a) Any person engaging in the transportation of persons or property for hire or compensation by or upon a motor vehicle upon any public highway in this State, either directly or indirectly.

(b) Any person who

for compensation furnishes any motor vehicle for the transportation of

persons or property under a lease or rental agreement when such person

operates the motor vehicle furnished or exercises any control of, or

assumes. any responsibility for the operation of the vehicle

irrespective of whether the vehicle is driven by such person or the

person to whom the vehicle is furnished, or engages either in whole or

in part in, the transportation of persons or property in the motor

vehicle furnished.

STATUTES OF CALIFORNIA 1955, Chapter 1905, Section I. Section 9603 of the Revenue and Taxation Code

"It will be observed from the language of the ordinance that a

distinction is to be drawn between the terms `operator' and `driver';

the `operator' of the service car being the person who is licensed to

have the car on the streets in the business of carrying passengers for hire; while the `driver' is the one who actually drives the car. However, in the actual prosecution of business, it was possible for the same person to be both `operator' and `driver.'"

Newbill vs. Union Indemnity Co., 60 SE.2d 658 (May 31, 1933)

STATUTES OF CALIFORNIA 1955

Chapter 1905

Section I.

Section 9603 of the Revenue and Taxation Code is amended to read:

9603. "Operator" includes:

(a) Any person engaging in the transportation of persons or property for hire or compensation by or upon a motor vehicle upon any public highway in this State, either directly or indirectly.

"Operator" does not include any of the following:

(a)

Any person transporting his own property in a motor vehicle owned or

operated by him unless he makes a specific charge for the

transportation.

"The word 'operator' shall not include any person who solely transports his own property and who transports no persons or property for hire or compensation."

California Statutes at Large, Chapter 412, p.8

The activity licensed by state DMVs - the operation of

motor vehicles - is itself integrally related to interstate

commerce.

Seth Waxman, Solicitor General

U.S. Department of Justice

BRIEF FOR THE PETITIONERS

Reno v. Condon, 528 U.S. 141, January 12, 2000

Supreme Court of the United States

A license proper is a permit to do business which could not be done without the license.

CITY AND COUNTY OF SAN FRANCISCO v. LIVERPOOL AND LONDON AND GLOBE INSURANCE COMPANY et al. (1887), 74 Cal. 113

A license in its proper sense is a permit to do business which could not be done without the license.

CITY OF SONORA v. J. B. CURTIN (1902) 137 Cal. 583

In California, a license is defined as "A permit, granted by an

appropriate governmental body, generally for a consideration, to a

person or firm, or corporation to pursue some occupation or to carry on

some business subject to regulation under the police power."

Rosenblatt v. California (1945) 69 Cal. App.2d 69

"For hire" - Compiled General Laws of Florida, s. 1280 (1927)

"For hire" as defined in this Chapter shall include all motor driven vehicles, or trailers hauled by a motor vehicle, in use for transporting persons, commodities or materials for compensation,

or such motor vehicles as may be let or rented to another for

consideration: Provided, that motor vehicles temporarily used by

farmers for the transportation of agricultural or horticultural

products from farms or grove to packing houses or to points of shipment

by transportation companies shall not be held to be operating for hire:

Provided, further, that motor vehicles used for transporting school

children to and from school under contract with school officials shall

not be deemed to be in use for hire.

"For hire" - Laws of Florida, c. 25418, s. 1(9)

"For

Hire" means any auto transportation company engaged in the

transportation of persons or property over the public highways of this

state for compensation,

which is not a common carrier or contract carrier but transports such

persons or property in single, casual and non recurring

trips. "For hire" carriage shall not be deemed to include

charter carriage as herein defined and no "for hire" carriage of passengers shall be authorized by any permit as herein defined and issued by the Commission under the provisions of this chapter in motor vehicles of a greater passenger-carrying capacity than seven, including the driver or chauffeur.

The state has the authority to regulate the use of public highways for business purposes.

Morel v. Railroad Commission of California (1938) 11 Cal.2d 488

Traffic - Webster's Unified Dictionary and Encyclopedia, International Illustrated Edition (1960)

1. Business or trade, commerce. 2. Transportation.

Traffic - Bouvier’s Law Dictionary (1856)

Commerce, trade,

Traffic - Black's Law Dictionary 3rd Ed.

Commerce; trade;

Traffic - Black's Law Dictionary 4th Ed.

Commerce; trade;

Traffic - Black's Law Dictionary, 6th Ed

Commerce; trade;

Transportation - Webster's Unified Dictionary and Encyclopedia, International Illustrated Edition (1960)

1. The act or business of moving passengers and goods. 2. The means of conveyance used.

Transportation - Black's Law Dictionary 3rd Ed.

The removal of goods or persons from one place to another, by a

carrier. See Railroad Co. v. Pratt, 22 Wall. 133, 22 L.Ed. 827;

Interstate Commerce Com'n v. Brimson, 154 U.S. 447, 14 Sup.Ct. 1125, 38

L.Ed. 1047; Gloucester Ferry Co. v. Pennsylvania, 114 U.S. 196, 5

Sup.Ct. 826, 29 L.Ed. 158.

Transportation - Black's Law Dictionary 4th Ed.

The removal of goods or persons

from one place to another, by a carrier. See Railroad Co. v. Pratt, 22

Wall. 133, 22 L.Ed. 827; Interstate Commerce Com'n v. Brimson, 154 U.S.

447, 14 Sup.Ct. 1125, 38 L.Ed. 1047; Gloucester Ferry Co. v.

Pennsylvania, 114 U.S. 196, 5 Sup.Ct. 826, 29 L.Ed. 158.

Transportation - Black's Law Dictionary, 6th Ed

The movement of goods or persons from one place to another, by a carrier.

Transportation - Words and Phrases

See

State v. Western Trans Co. (1950, Iowa) 43 N.W.2d 739 [The judge, after

giving his conclusion, goes on to give examples of "transportation" -

all involving the movement of persons or goods for hire.]

CAR'RIER, n. [See Carry.] One who carries; that which carries or conveys ; also a messenger.

2. One who is employed to carry goods for others for a reward; also, one whose occupation

is to carry goods for others, called a common carrier; a porter-

Webster’s Dictionary, 1828 (no page numbers provided in original)

CARRY: Carrying trade, the trade which consists in the transportation of goods by water from

country to country, or place to place.

Webster’s Dictionary, 1828 (no page numbers provided in original)

CARRIERS,

contracts. There are two kinds of carriers, namely, common

carriers, (q.v.) who have been considered under another head; and

private carriers. These latter are persons who, although

they do not undertake to transport the goods of such as choose to

employ them, yet agree to carry the goods of some particular person for

hire, from one place to another.

2. In such case the carrier incurs no responsibility

beyond that of any other ordinary bailee for hire, that is to say, the

responsibility of ordinary diligence. 2 Bos. & Pull. 417; 4 Taunt.

787; Selw. N. P. 382 n.; 1 Wend. R. 272; 1 Hayw. R. 14; 2 Dana, R. 430;

6 Taunt. 577; Jones, Bailm. 121; Story on Bailm, Sec. 495. But in

Gordon v. Hutchinson, 1 Watts & Serg.

285, it was holden that a Wagoner Who carries goods for hire,

contracts, the responsibility of a common carrier, whether

transportation be his principal and direct business, or only an

occasional and incidental employment.

3. To bring a person within the description of a

common carrier, he must exercise his business as a public employment;

he must undertake to carry goods for persons generally; and he must

hold himself out as ready to engage in the transportation of goods for

hire, as a business; not as a casual occupation pro hac vice. 1 Salk.

249; 1 Bell's Com. 467; 1 Hayw. R.

14; 1 Wend. 272; 2, Dana, R. 430. See Bouv. Inst. Index, b. t.

Bouvier’s Law Dictionary, 1856, p. 14

COMMON CARRIER,

contracts. One who undertakes for hire or reward to

transport the goods of any who may choose to employ him, from place to

place. 1 Pick. 50, 53; 1 Salk. 249, 250; Story, Bailm. Sec. 495 1 Bouv.

Inst. n. 1020.

2. Common carriers are generally of two

descriptions, namely, carriers by land and carriers by

water. Of the former description are the proprietors of

stage coaches, stage wagons or expresses, which ply between different

places, and' carry goods for hire; and truckmen, teamsters, cartmen,

and porters, who undertake to carry goods for hire, as a common

employment, from one part of a town or city to another, are also

considered as common carriers. Carriers by water are the

masters and owners of ships and steamboats engaged in the

transportation of goods for persons generally, for hire and lightermen,

hoymen, barge-owners, ferrymen, canal boatmen, and others employed in

like manner, are so considered.

3. By the common law, a common carrier is

generally liable for all losses which may occur to property entrusted

to his charge in the course of business, unless he can prove the loss

happened in consequence of the act of God, or of the enemies of the

United States, or by the act of the owner of the property. 8 S. &

R. 533; 6 John. R. 160; 11 John. R. 107; 4 N. H. Rep.

304; Harp. R. 469; Peck. R. 270; 7 Yerg. R. 340; 3 Munf. R. 239; 1 Conn. R. 487; 1 Dev. & Bat. 273; 2 Bail. Rep. 157.

Bouvier’s Law Dictionary, 1856, p. 89 - 93

COMMON CARRIERS OF PASSENGERS.

Common carriers of passengers are such as undertake for hire to

carryall persons indifferently who may apply for passage. Thomp. Carr.

p. 26. n. § 1.

Black’s Law Dictionary, 1st Ed. 1891, p. 230 - 231

Common and private carriers.

Carriers are either common or private. Private carriers are

persons who undertake for the transportation in a particular instance

only, not making it their vocation, nor bolding themselves out to the

public as ready to act for all who desire their services. Allen v.

Sackrider, 37 N. Y. 341. To bring a person within the

description of a common carrier, he must exercise it as a public

employment; be must undertake to carry goods for persons

generally; and he must hold himself out as ready to transport

goods for hire, as a business, not as a casual occupation, pro hac

vice. Alexander v. Greene, 7 Hill (N. Y.) 564, Bell v. Pidgeon,

(D. C.) 5 Fed. 634: Wyatt v. Irr. Co., 1 Colo. App. 480, 29 Pac.

906. A common carrier may therefore be defined as one who, by virtue of

his calling and as a regular business, undertakes for hire to transport

persons or commodities from place to place, offering his services to

all such as may choose to employ him and pay his charges. Iron Works v.

Hurlbut, 158 N. Y. 34. 52 N. E. 665. 70 Am. St. Rep. 432: Dwight v.

Brewster. 1 Pick. (Mass.) 53. 11 Am. Dec. 133; Railroad Co. v.

Waterbury Button Co., 24 Conn. 479: Fuller v. Bradley. 25 Pa. 120:

McDuffee v. Railroad Co.. 52 N. H. 447, 13 Am. Rep. 72; Piedmont

Mfg. Co. v. Railroad Co., 19 S. C. 364. By statute in several

statestes it is declared that eyery one who offers to the public to

carry persons, property, or messages, excepting only telegraphic

messages, is a common carrier of whatever he thus offers to

carry. Civ. Code Cal. §2168; Civ. Code Mont. §2870; Rev. St. Okl.

1903 §700: Civ. Code N. D. 1903. §1899 . Common carriers are of two

kinds, - by land, as owners of stages, stage-wagons, railroad cars,

teamsters, cartmen, draymen, and porters: and by water, as owners of

ships, steam-boats, barges, ferrymen, lightermen, and canal boatmen. 2

Kent. Comm. 597. - Common carriers of passengers. Common

carriers of passengers are such as undertake for hire to carry all

persons indifferently who may apply for passage. Gillingham v.

Railroad Co.. 35 W. Va.. 588. 14 S. E. 243, 14 L. R. A.

798, 29 Am. St. Rep. 827; Electric Co. v. Simon, 20 Or. 60. 25

Pac. 147, 10 L. R. A. 251, 23 Am. St. Rep. 86: Richmond v.

Southern Pac. Co., 41 Or. 54., 67 Pac. 947, 57 L. R. A. 616, 93 Am. St.

Rep. 694.

Black’s Law Dictionary, 2nd Ed. 1910, p. 172

CARTMEN. Carriers who transport good and merchandise in carts, usually for short distances, for hire.

Black’s Law Dictionary, 2nd Ed. 1910, p. 173

CALIFORNIA VEHICLE CODE

DIVISION 1. WORDS AND PHRASES DEFINED

Motor Vehicle

415. (a) A “motor vehicle” is a vehicle that is selfpropelled.

Vehicle

670. A "vehicle" is a device

by which any person or property may be propelled, moved, or drawn upon

a highway, excepting a device moved exclusively by human power or used

exclusively upon stationary rails or tracks.

Commercial Vehicle

260. (a)

A “commercial vehicle” is a motor vehicle of a type required to be

registered under this code used or maintained for the transportation of

persons for hire, compensation, or profit or designed, used, or

maintained primarily for the transportation of property.

(b)

Passenger vehicles and house cars that are not used for the

transportation of persons for hire, compensation, or profit are not

commercial vehicles.

WEST'S ANNOTATED

Commercial Code

© 1990

§9109. Classification of Goods: "Consumer goods"; "Equipment"; "Farm Products"; "Inventory"

Goods are

(1) "Consumer goods" if they are used or bought for use primarily for personal, family or household purposes;

(2) "Equipment"

if they are used or bought for the use primarily in business (including

farming or a profession) or by a debtor who is a nonprofit organization

or a government subdivision or agency or if the goods are not included

in the definitions of inventory, farm products, or consumer goods.

California Code Comment

By John A. Bohn and Charles J. Williams

Prior California Law

1.

The classification of goods in this section is new statutory

law. The significance of this classification is

described in

Official Comment 1.

Although goods cannot belong to

more than one category at any time, they may change their

classification depending upon who holds them and for what

reason. Each classification is mutually exclusive but the

four classifications described are intended to include all goods.

Official Comment 2.

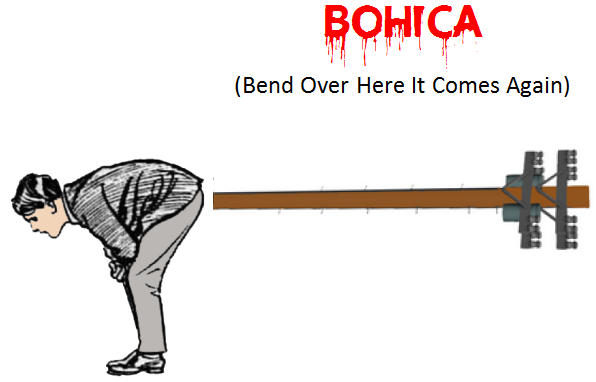

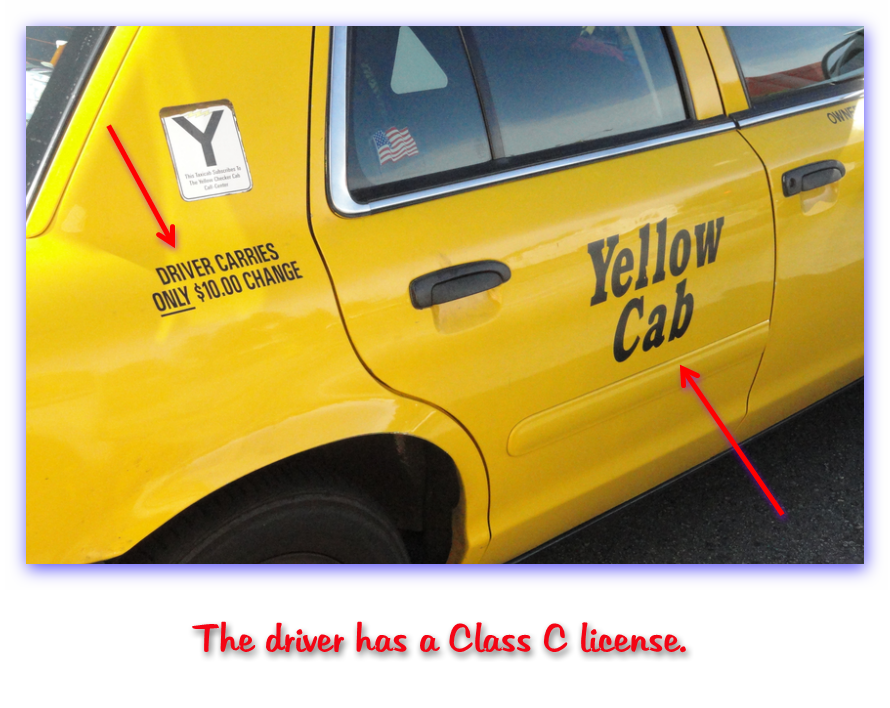

The images are a "vehicle", which are

used for commercial purposes and to which the State government may

regulate and control, which it has:

CALIFORNIA CIVIL CODE

PART 3. PERSONAL OR MOVABLE PROPERTY

TITLE 1. PERSONAL PROPERTY IN GENERAL

1689.5. As used in Sections 1689.6 to 1689.11, inclusive, and in Section 1689.14:

(c) "Goods" means tangible chattels bought for use primarily for personal, family, or household purposes,

including certificates or coupons exchangeable for these goods, and

including goods that, at the time of the sale or subsequently, are to

be so affixed to real property as to become a part of the real property

whether or not severable therefrom, but does not include any vehicle required to be registered under the Vehicle Code,

1791. As used in this chapter:

(a)

"Consumer goods" means any new product or part thereof that is used,

bought, or leased for use primarily for personal, family, or household

purposes, except for clothing and consumables. "Consumer goods" shall

include new and used assistive devices sold at retail.

CALIFORNIA CODE OF CIVIL PROCEDURE

481.100. "Equipment"

means tangible personal property in the possession of the defendant and

used or bought for use primarily in the defendant's trade, business, or

profession ...

CALIFORNIA VEHICLE CODE

§15210 (p)(8) In the absence of a federal definition, existing definitions under this code shall apply.

THERE EXIST FEDERAL DEFINITIONS:

Title 18 United States Code Sec. 31

TITLE 18 - CRIMES AND CRIMINAL PROCEDURE

PART I - CRIMES

CHAPTER 2 - AIRCRAFT AND MOTOR VEHICLES

Sec. 31. Definitions

STATUTE

When used in this chapter the term -

''Motor

vehicle'' means every description of carriage or other contrivance

propelled or drawn by mechanical power and used for commercial purposes

on the highways in the transportation of passengers, passengers and

property, or property or cargo; ''Used for commercial purposes''

means the carriage of persons or property for any fare, fee, rate,

charge or other consideration, or directly or indirectly in connection

with any business, or other undertaking intended for profit;...

CODE OF FEDERAL REGULATIONS

Title 49, Volume 4, Parts 200 to 399 Revised as of October 1, 1999 From the U.S. Government Printing Office via GPO Access CITE: 49 CFR 390

[Page 859 - 865]

TITLE 49 -- TRANSPORTATION CHAPTER III--FEDERAL HIGHWAY ADMINISTRATION, DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION

PART 390--FEDERAL MOTOR CARRIER SAFETY REGULATIONS; GENERAL--Table of Contents Subpart A--General Applicability and Definitions

Sec. 390.1 Purpose.

This part establishes general applicability, definitions, general

requirements and information as they pertain to persons subject to this

chapter.

Sec. 390.3 General applicability.

(a) The rules in subchapter B

of this chapter are applicable to all employers, employees, and

commercial motor vehicles, which transport property or passengers in

interstate commerce.

Sec. 390.5 Definitions.

Driver - means any person who operates any commercial motor vehicle.

Interstate commerce - means trade, traffic, or transportation in the United States –

(1) Between a place in a State and a place outside of such State (including a place outside of the United States);

(2) Between two places in a State through another State or a place outside of the United States; or

(3) Between two places in

a State as part of trade, traffic, or transportation originating or

terminating outside the State or the United States.

Intrastate commerce - means any trade, traffic, or transportation in any State which is not described in the term ``interstate commerce.''

Motor vehicle - means any vehicle, machine, tractor, trailer, or semitrailer propelled or drawn by mechanical power and used upon the highways in the transportation of passengers or property,

or any combination thereof determined by the Federal Highway

Administration, but does not include any vehicle, locomotive, or car

operated exclusively on a rail or rails, or a trolley bus operated by

electric power derived from a fixed overhead wire, furnishing local

passenger transportation similar to street-railway service.

Operator -- See driver.

“A chauffeur, within the sense defined in Veh. Code § 71, is one who is paid compensation for his services.”

Hutton v. California Portland Cement Co. (1942), 50 CA2d. 684

"... Section 1 [of the Motor Vehicle Act] excludes from the definition

of the term 'operator' everyone 'who solely transports by motor vehicle

... his or its own property, or employees, or both, and who transports

no persons or property for hire or compensation.'"

Bacon Service Corporation v. Huss (1926) 199 Cal. 21

Operator -- See driver.

Operator -- See driver.

AUTO LIVERY SERVICE.

The business of furnishing for hire an automobile with a chauffeur, the

car to be driven where the hirer directs. The term is also

applied to the business of leasing driverless cars.

See Collette v. Page, 44 R.I. 26, 114 A. 136, 18 A.L.R. 74. See Automobile; Drive it Yourself Cars.

AUTO STAGE. A motor vehicle used for the purpose of

carrying passengers, baggage, or freight on a regular schedule of time

and rates.

State v. Ferry Line Auto Bus Co., 99 Wash. 64, 168 P. 893, 894. See Automobile.

LEGAL MAXIMS

VOLENTI NON FIT INJURIA:

Latin for "to a willing person, it is not a wrong." This

legal maxim holds that a person who knowingly and voluntarily risks

danger cannot recover for any resulting injury.

IGNORANTIA LEGIS NEMINEM EXCUSAT: Latin maxim meaning “ignorance of the law does not excuse” or “ignorance of the law excuses no one.”

This maxim is often shortened to ignorantia juris. This

maxim is also termed as ignorantia juris non excusat, ignorantia legis

non excusat, ignorantia juris haud excusat. Originally,

this maxim was formulated when the list of crimes represented current

morality, but now there are many crimes as a result of administrative

or social regulation. The American legal system has

recognized certain exceptions to the rule of ignorantia juris,

especially in Lambert v. California and Cheek v. United States.

The law imputes knowledge of all laws to all individuals within its

jurisdiction. The rationale behind the maxim is that if

ignorance of law was recognized as an excuse, individuals charged with

criminal offenses or subject to a civil lawsuit would merely claim

unawareness of law in question to escape liability even if s/he exactly

knows what the law in question is. Therefore, the rule

assumes that the law in question was properly published, distributed or

printed in an official gazette, and made available to the public over

the internet or printed in volumes for sale to public at affordable

prices.

We thus require citizens to apprise themselves not only of statutory

language but also of legislative history, subsequent judicial

construction, and underlying legislative purposes. (See generally

Amsterdam, The Void-For-Vagueness Doctrine in the Supreme Court (1960)

109 U. Pa. L.Rev. 67.)

Walker v. Superior Court (1988) 47 Cal.3d 112

People v. Grubb (1965) 63 Cal. 2d 614

Approved December 31, 1974 (88 Stat. 1896)

Public Law 93-579, as codified at 5 U.S.C. 552a

Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the

United States of America in Congress assembled, that this Act may be

cited as the "Privacy Act of 1974.

SECTION 3

(a) DEFINITIONS

For purposes of this section --

(2) the term "individual" means a citizen of the United States or an alien lawfully admitted for permanent residence;

Government web site: http://www.ssa.gov/OP_Home/comp2/F093-579.html

The United States of America is a corporation

endowed with the capacity to sue and be sued, to convey and

receive property. 1 Marsh. Dec. 177, 181. But it is proper to observe

that no suit can be brought against the United States without authority

of law.”

Bouvier’s Law Dictionary, 5th, definition of “United States”

“In clause (4), the words ‘United States’ are substituted for the words ‘Federal Government’.”

10 U.S.C.S. (United States Code Service), '2231(4), History: Ancillary Laws and Directives, p. 19

TITLE 28, UNITED STATES CODE, PART VI,

CHAPTER 176, Judicial and Judiciary Procedure, SUB CHAPTER

A, Sec. 3002. Definitions (15), p. 564, ''United States''

means -

(A) a Federal corporation;

(B)

an agency, department, commission, board, or other entity of the United

States; or

(C) an instrumentality of the United States

"The government of the United States is a foreign corporation with respect to a state."

In re Merriam, 36 N. E. 505, 141 N. Y. 479, affirmed 16 S. Ct. 1073, 163 U. S. 625, 41 L.Ed. 287.

CALIFORNIA COMMERCIAL CODE

SECTION 9301 - 9342

9307. (h) The United States is located in the District of Columbia.

"...the United States, in Congress assembled."

The Articles of Confederation, Nov. 15, 1777

(The forgoing is used 28 times in that document.)

"A citizen of the United States is a citizen of the federal government ..."

Kitchens v. Steele (1953) 112 F.Supp 383, United States District Court W. D. Missouri, W. D.

“There are, then, under our republican form of government, two classes

of citizens, one of the United States and one of the state”.

Gardina v. Board of Registrars of Jefferson County, 160 Ala. 155; 48 So. 788 (1909)

“We have in our political system a government of the United States and

a government of each of the several States. Each one of

these governments is distinct from the others, and each has citizens of

it’s own...”

United States v. Cruikshank, 92 U.S. 542 (1875)

“It is quite clear, then, that there is a citizenship of the United

States, and a citizenship of a state, which are distinct from each

other and which depend upon different characteristics or circumstances

in the individual”.

Slaughter-House Cases, 83 U.S. 36 (16 Wall.); 21 L.Ed. 394 (1873)

“...there was no such thing as citizen of the United States, except as that condition arose from citizenship of some state.”

United States v. Anthony, 24 Fed. Cas. 829, (Case No. 14,459)(1873)

"The term 'Citizen of the United States' must be understood to mean

those who were citizens of the State as such after the Union had

commenced and the several States had assumed their sovereignty.

Before that period there were no citizens of the United States."

Inhabitants of Manchester v. Inhabitants of Boston, 16 Mass. 230, 235.

“...he was not a citizen of the United States, he was a citizen and

voter of the State,...” “One may be a citizen of a State and yet

not a citizen of the United States”.

McDonel v. The State, 90 Ind. 320 (1883)

““Citizenship” and “residence”, as has often been declared by the courts, are not convertible terms. ...

“”The better opinion seems to be that a citizen of the United States

is, under the amendment [14th], prima facie a citizen of the state

wherein he resides , cannot arbitrarily be excluded therefrom by such

state, but that he does not become a citizen of the state against his

will, and contrary to his purpose and intention to retain an already

acquired citizenship elsewhere. The amendment [14th] is a

restraint on the power of the state, but not on the right of the person

to choose and maintain his citizenship or domicile”“.

Sharon v. Hill, 26 F. 337 (1885) [inserts added]

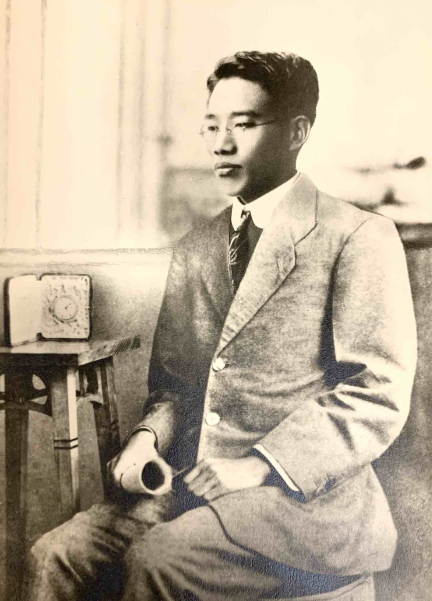

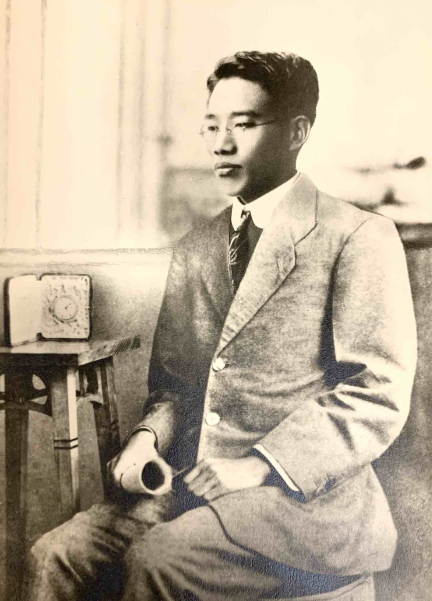

Dr. Kikuo Tashiro, 1918

Dr. Kikuo Tashiro, 1918

“That there is a citizenship of the United States and citizenship of a state”,...

Tashiro v. Jordan (1927)201 Cal. 236

"Except as modified by statute, the place of birth governs citizenship status".

Rogers v. Bellei, 401 U. S. 815; 28 L.Ed.2d 499; 91 S.Ct. 1060 (1971).

"The United States and the State of California are two separate sovereignties, each dominant in its own sphere."

Redding v. Los Angeles (1947), 81 C.A.2d 888

THEREFORE, YOU'RE EITHER A CITIZEN OF ONE OF THESE...

OR YOU'RE A CITIZEN OF THIS...

“There is a difference between privileges and immunities belonging to

the citizens of the United States as such, and those belonging to the

citizens of each state as such”.

Ruhstrat v. People, 57 N.E. 41 (1900)

“The rights and privileges, and immunities which the fourteenth

constitutional amendment and Rev. St. section 1979 [U.S. Comp. St.

1901, p. 1262], for its enforcement, were designated to protect, are

such as belonging to citizens of the United States as such, and not as

citizens of a state”.

Wadleigh v. Newhall, 136 F. 941 (1905)

“The governments of the United States and of each state of the several

states are distinct from one another. The rights of a

citizen under one may be quite different from those which he has under

the other”.

Colgate v. Harvey, 296 U.S. 404; 56 S.Ct. 252 (1935)

“...rights of national citizenship as distinct from the fundamental or natural rights inherent in state citizenship”.

Madden v. Kentucky, 309 U.S. 83: 84 L.Ed. 590 (1940)

[2] The people of the State of California are supreme and have the

undoubted right to protect themselves and to preserve the form of

government...

Steiner v. Darby (1948) 88 Cal.App.2d 481

"The people are such as are born upon the soil, by whom and for whom in the first place the Government was ordained...."

Walther v. Rabolt (1866) 30 Cal. 185

CALIFORNIA GOVERNMENT CODE

11120.

It is the public policy of this state that public agencies exist to aid

in the conduct of the people's business and the proceedings of public

agencies be conducted openly so that the public may remain informed.

In enacting this article the Legislature finds and declares that it is

the intent of the law that actions of state agencies be taken openly

and that their deliberation be conducted openly.

The people of this state do not yield their sovereignty to the agencies

which serve them. The people, in delegating authority, do

not give their public servants the right to decide what is good for the

people to know and what is not good for them to know. The

people insist on remaining informed so that they may retain control

over the instruments they have created.

This article shall be known and may be cited as the Bagley-Keene Open Meeting Act.

54950 DECLARATION OF LEGISLATIVE PURPOSE.

"In enacting this chapter, the Legislature finds and declares that the

public commissions, boards and councils and the other public agencies

in this State exist to aid in the conduct of the people's

business. It is the intent of the law that their actions be

taken openly and that their deliberations be conducted openly.

The people of this State do not yield their sovereignty to the agencies

which serve them. The people, in delegating authority, do

not give their public servants the right to decide what is good for the

people to know and what is not good for them to know. The people

insist on remaining informed so that they may retain control over the

instruments they have created".