Welcome to Red Pill Country

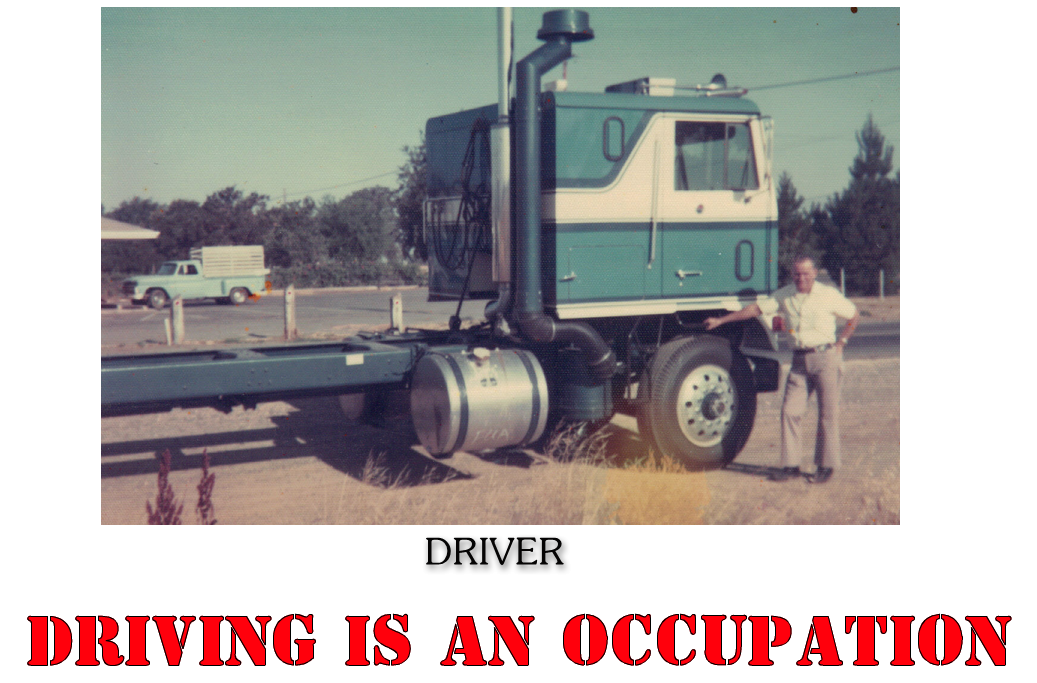

Driving a vehicle

and being in actual control of a vehicle are not

synonymous.

Driving a vehicle

and being in actual control of a vehicle are not

synonymous.

Mercer v. Department of Motor Vehicles (1991) 53 Cal.3d 753

Are

you sure, are you certain, that when you use your car, truck, van or

motorcycle to go somewhere that you're "driving"? Would you bet

a month's salary on it?

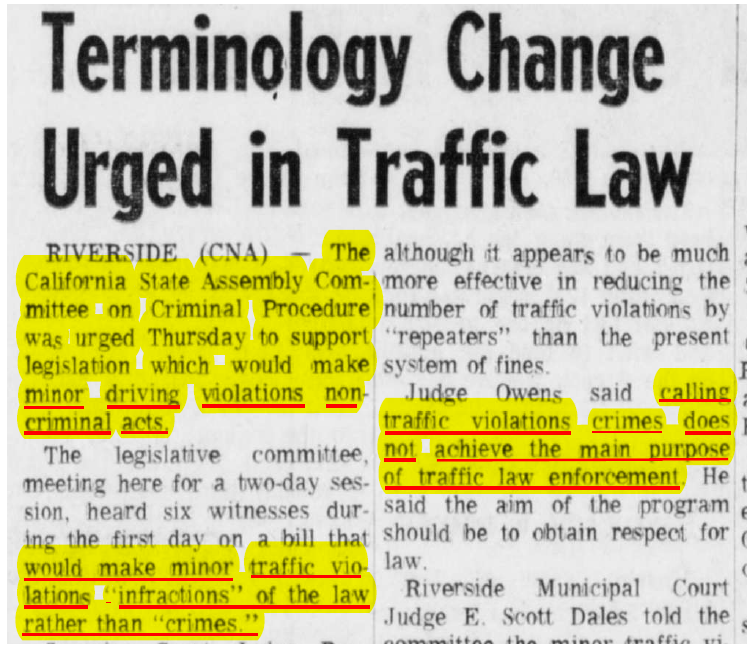

Everyone should know that the Legislature makes the laws. They write them. They use words. They provide the definitions of the words they use in the laws they write. The Codes of California contain the laws. The Codes of California also contain the definitions of the words that comprise the law.

All the following words are defined in the Vehicle Code: Alley, All-Terrain Vehicle, Bicycle, Camper, Chop Shop, Crosswalk, Darkness, Driver, Driver License, Garage, Highway, Motor Vehicle, Motorcycle, Muffler, Parking, Passenger, Pedestrian, Person, Resident, Sidewalk, Snow-tread Tire, Street, Transportation, Vehicle, to name but a few. BUT...

Everyone should know that the Legislature makes the laws. They write them. They use words. They provide the definitions of the words they use in the laws they write. The Codes of California contain the laws. The Codes of California also contain the definitions of the words that comprise the law.

All the following words are defined in the Vehicle Code: Alley, All-Terrain Vehicle, Bicycle, Camper, Chop Shop, Crosswalk, Darkness, Driver, Driver License, Garage, Highway, Motor Vehicle, Motorcycle, Muffler, Parking, Passenger, Pedestrian, Person, Resident, Sidewalk, Snow-tread Tire, Street, Transportation, Vehicle, to name but a few. BUT...

...the very word that everyone believes they do when they go anywhere for any reason in their car, truck, van, or on their motorcycle...

...IS NOT DEFINED IN ANY OF THE CALIFORNIA CODES!

DON'T BELIEVE ME, LOOK FOR YOURSELF, I DID! THAT'S RIGHT, I WENT THROUGH EVERY CALIFORNIA

CODE LOOKING FOR THE DEFINITION OF THAT WORD AND IT'S NOT IN ANY OF THEM! BUT YOU "BELIEVE"

THAT'S WHAT YOU DO WHEN YOU GO ANYWHERE FOR ANY REASON. WHAT IF YOU'RE WRONG? WELL IF

YOU PROCEED PAST THIS POINT YOU'RE GOING TO LEARN THAT YOU ARE!

CODE LOOKING FOR THE DEFINITION OF THAT WORD AND IT'S NOT IN ANY OF THEM! BUT YOU "BELIEVE"

THAT'S WHAT YOU DO WHEN YOU GO ANYWHERE FOR ANY REASON. WHAT IF YOU'RE WRONG? WELL IF

YOU PROCEED PAST THIS POINT YOU'RE GOING TO LEARN THAT YOU ARE!

No one you know has ever SEEN the

legal definition of the word DRIVING, not even the police, CHP or

Sheriff deputies, Pro Tems, Traffic Court Commissioners and judges,

because the LAW MAKERS of the Legislative branch of government have not

provided a definition of that word. In order to determine

what that word means you have to read court cases. It's also a

real good idea to investigate the history of the machine we use to go

anywhere then you'll know what that word means.

Who taught you what you know about the Driver License, DMV, traffic stops, motor vehicles, driving and driver? I'll bet it was adults, beginning with family members, and then teachers, but adults just the same.

Yeah, thanks to the adults, who were mislead, and who taught us, we were mislead too. The adults let us believe something contrary to what you just read at Art. 1, Sec. 1 of the State Constitution that secures our unalienable rights. No license, or permission, is required from our government employees to exercise a secured unalienable right. In other words the people for whom government was created, are not required to ask their employees for permission to use or exercise any of the unalienable rights they swore an oath to protect and defend.

Everyone BELIEVES that's what they're doing when they go ANYWHERE for ANY REASON. No one has ever SEEN the definition provided by their LAW MAKERS up at the State Capitol because, at least here in California, the Legislature has NOT DEFINED THAT WORD! The LAW MAKERS have not defined the VERB the Driver License permits. They did provided a definition for the NOUN permitted to be used by the license, MOTOR VEHICLE, but NOT the ACTION WORD or VERB permitted by the Driver License! So again, would you bet a month's salary you KNOW what the definition of DRIVING is?

Everyone also BELIEVES driving is a privilege, and that's true. When did your right to use your property to go get food or other necessities become a privilege and you had to pay for it before you could use your property to go grocery shopping or to your place of worship? When did it become a privilege to use your propert to take your kids to school or to visit granny or gramps? When did it become a privilege to use your property to take a family member to a doctor's appointment or to the hospital for medical care if they needed it? When did it become a privilege to use your property to take yourself to the doctor if you needed stitches? When did it become a privilege to go visit a family member or friend in the hospital? WHEN DID IT BECOME A PRIVILEGE TO ATTEND A FAMILY MEMBER OR FRIEND'S FUNERAL USING YOUR CAR, TRUCK, VAN OR MOTORCYCLE?????

NOTE: WOMEN ARE INCLUDED IN THAT FIRST PART.

So what's vague and ambiguous about what you read at Art. 1, Sec. 1? That means something or it's bullshit. I believe it's the former not the latter. So when the hell did your RIGHT become a PRIVILEGE and WHO changed it? Did you? How did going to get food or attend a funeral or seeking medical care using what you have the UNALIENABLE right to acquire and use become a PRIVILEGE?

Or what if what you believe isn't correct? What if you've been lied to? What if you've been mislead? What if no one taught you want a LICENSE permitted? What if the PRIVILEGE the license permits has to do with the COMMERCIAL USE of the streets and highways and you don't HAVE TO HAVE ONE if you don't use the streets and highways to deliver anyone or anything as your job?

The people of California own the streets and highways, not the government employees. Consider if you owned a horse ranch and you and a friend wanted to go for a ride on a couple of your horses around your ranch. When you go out to the stable do you ask the stable boy for his permission to ride your horses or do issue an instruction to saddle up the bay and Arabian? This is the LAW:

I'll bet the adults didn't tell you that either. Notice the FIRST time that unalienable right was acknowledged was 1924, then again using the same exact words in 1950, and by the California Supreme Court by the way so that issue is settled! It's a fact and if your belief is contrary to that fact then you need to make an adjustment to your belief system because it does not comport with the LAW.

So you've been lead to believe you HAVE TO, are REQUIRED TO ask your stable boy for his permission to use your property on your property. But at Art. 1, Sec. 1 you read you are free and have unalienable rights like acquiring a car, truck, van or motorcycle to get around on the streets and highways that you have the UNALIENABLE RIGHT to use.

Who taught you what you know about the Driver License, DMV, traffic stops, motor vehicles, driving and driver? I'll bet it was adults, beginning with family members, and then teachers, but adults just the same.

Yeah, thanks to the adults, who were mislead, and who taught us, we were mislead too. The adults let us believe something contrary to what you just read at Art. 1, Sec. 1 of the State Constitution that secures our unalienable rights. No license, or permission, is required from our government employees to exercise a secured unalienable right. In other words the people for whom government was created, are not required to ask their employees for permission to use or exercise any of the unalienable rights they swore an oath to protect and defend.

Everyone BELIEVES that's what they're doing when they go ANYWHERE for ANY REASON. No one has ever SEEN the definition provided by their LAW MAKERS up at the State Capitol because, at least here in California, the Legislature has NOT DEFINED THAT WORD! The LAW MAKERS have not defined the VERB the Driver License permits. They did provided a definition for the NOUN permitted to be used by the license, MOTOR VEHICLE, but NOT the ACTION WORD or VERB permitted by the Driver License! So again, would you bet a month's salary you KNOW what the definition of DRIVING is?

Everyone also BELIEVES driving is a privilege, and that's true. When did your right to use your property to go get food or other necessities become a privilege and you had to pay for it before you could use your property to go grocery shopping or to your place of worship? When did it become a privilege to use your propert to take your kids to school or to visit granny or gramps? When did it become a privilege to use your property to take a family member to a doctor's appointment or to the hospital for medical care if they needed it? When did it become a privilege to use your property to take yourself to the doctor if you needed stitches? When did it become a privilege to go visit a family member or friend in the hospital? WHEN DID IT BECOME A PRIVILEGE TO ATTEND A FAMILY MEMBER OR FRIEND'S FUNERAL USING YOUR CAR, TRUCK, VAN OR MOTORCYCLE?????

Constitution of the State of California

Article I: Declaration of Rights

Sec. 1.

Article I: Declaration of Rights

Sec. 1.

All men are by nature free and independent, and have certain unalienable rights, among which are those of enjoying

and defending life and liberty: acquiring, possessing and protecting property: and pursuing and obtaining safety and happiness, and privacy.

and defending life and liberty: acquiring, possessing and protecting property: and pursuing and obtaining safety and happiness, and privacy.

NOTE: WOMEN ARE INCLUDED IN THAT FIRST PART.

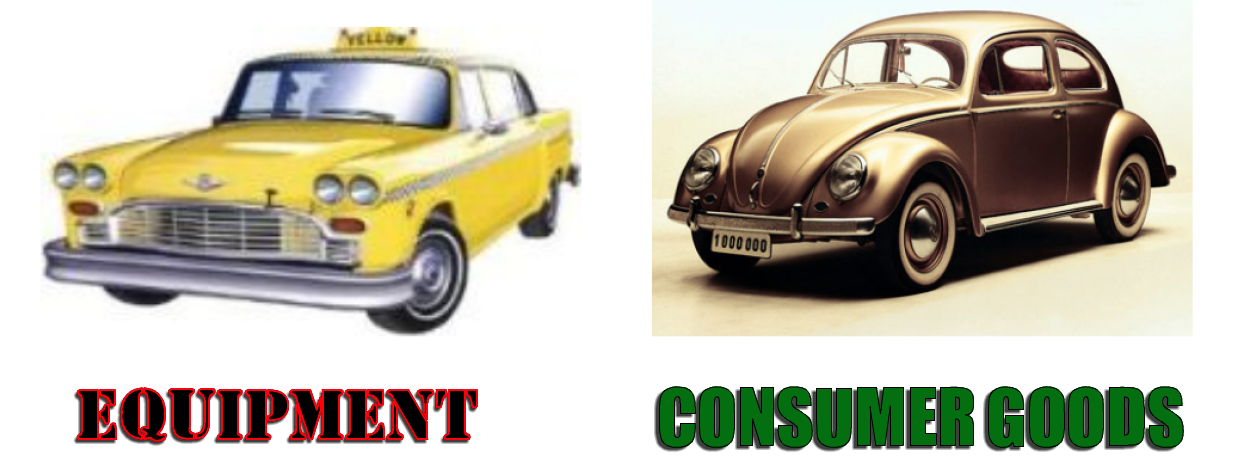

THESE MACHINES ARE PROPERTY

So what's vague and ambiguous about what you read at Art. 1, Sec. 1? That means something or it's bullshit. I believe it's the former not the latter. So when the hell did your RIGHT become a PRIVILEGE and WHO changed it? Did you? How did going to get food or attend a funeral or seeking medical care using what you have the UNALIENABLE right to acquire and use become a PRIVILEGE?

Or what if what you believe isn't correct? What if you've been lied to? What if you've been mislead? What if no one taught you want a LICENSE permitted? What if the PRIVILEGE the license permits has to do with the COMMERCIAL USE of the streets and highways and you don't HAVE TO HAVE ONE if you don't use the streets and highways to deliver anyone or anything as your job?

The people of California own the streets and highways, not the government employees. Consider if you owned a horse ranch and you and a friend wanted to go for a ride on a couple of your horses around your ranch. When you go out to the stable do you ask the stable boy for his permission to ride your horses or do issue an instruction to saddle up the bay and Arabian? This is the LAW:

It

is settled that the streets of a city belong to the people of a state

and the use thereof is an inalienable right of every citizen of the

state.

Whyte v. City of Sacramento (1924) 65 Cal. App. 534

Escobedo v. State Dept. of Motor Vehicles (1950) 35 Cal.2d 870

Whyte v. City of Sacramento (1924) 65 Cal. App. 534

Escobedo v. State Dept. of Motor Vehicles (1950) 35 Cal.2d 870

I'll bet the adults didn't tell you that either. Notice the FIRST time that unalienable right was acknowledged was 1924, then again using the same exact words in 1950, and by the California Supreme Court by the way so that issue is settled! It's a fact and if your belief is contrary to that fact then you need to make an adjustment to your belief system because it does not comport with the LAW.

So you've been lead to believe you HAVE TO, are REQUIRED TO ask your stable boy for his permission to use your property on your property. But at Art. 1, Sec. 1 you read you are free and have unalienable rights like acquiring a car, truck, van or motorcycle to get around on the streets and highways that you have the UNALIENABLE RIGHT to use.

If you have one of these...

...then you have permission to "drive" one of these:

That machine is used for commercial or business purposes.

That permission card permits her to do commerce or business using one of those types of machines.

And notice the word the arrow points at, that word is a JOB TITLE.

That machine is used for commercial or business purposes.

That permission card permits her to do commerce or business using one of those types of machines.

And notice the word the arrow points at, that word is a JOB TITLE.

Here's some more of what the adults didn't tell you:

The state has the authority to regulate the use of public highways for business purposes.

Morel v. Railroad Commission of California (1938) 11 Cal.2d 488

The state has the authority to regulate the use of public highways for business purposes.

Morel v. Railroad Commission of California (1938) 11 Cal.2d 488

You see what the LAW MAKERS did? They combined TWO license into one. So that license in your wallet or purse permits you to be hired as a DRIVER to DRIVE. It's also EVIDENCE you use your machine and the streets and highways for commercial or business purposes. Is it becoming clearer what DRIVING is even without an OFFICIAL definition provided by the LAW MAKERS?

I'll bet the adults didn't tell you that either!

That woman is soliciting a ride. When she gets in that cab she will be paying for the ride. She will be a PASSENGER.

A PA$$ENGER = CU$TOMER

Do the people who ride with you pay? Are they a PASSENGER or are they your GUEST?

These people have no idea what they're standing in line for.

They're about to apply (request) for permission to use their car for commercial or business purposes on the streets and highways.

But that's not what they were lead to believe before they decided to stand in line.

Cal Worthington and his dog Spot after havin all the fun at the DMV

Persons

dealing with a public agency are presumed to know the law and

are bound at their peril to ascertain and follow those procedures

necessary to enter into a binding contract. (See Miller v. McKinnon,

supra, 20 Cal.2d at p. 89; Bear River etc. Corp. v. County of Placer

(1953) 118 Cal.App.2d 684 , 690 [258 P.2d 543].)

SEYMOUR v. STATE OF CALIFORNIA, 156 Cal.App.3d 200

[Civ. No. 22606. Court of Appeals of California, Third Appellate District. March 9, 1984.]

SEYMOUR v. STATE OF CALIFORNIA, 156 Cal.App.3d 200

[Civ. No. 22606. Court of Appeals of California, Third Appellate District. March 9, 1984.]

I'm

confident each and everyone one of them knows exactly what they're

doing having carefully studied the rules.

So once they fill out the form, take all the tests, and pay for their employee's permission, the rules in the Vehicle Code will apply to them. They have NO IDEA how many rules apply to them. If you want to know then take a look at Appendix B of the California Vehicle Code. There's felonies, misdemeanors and infractions listed, lots and lots and lots of each and no one knows what any of them are.

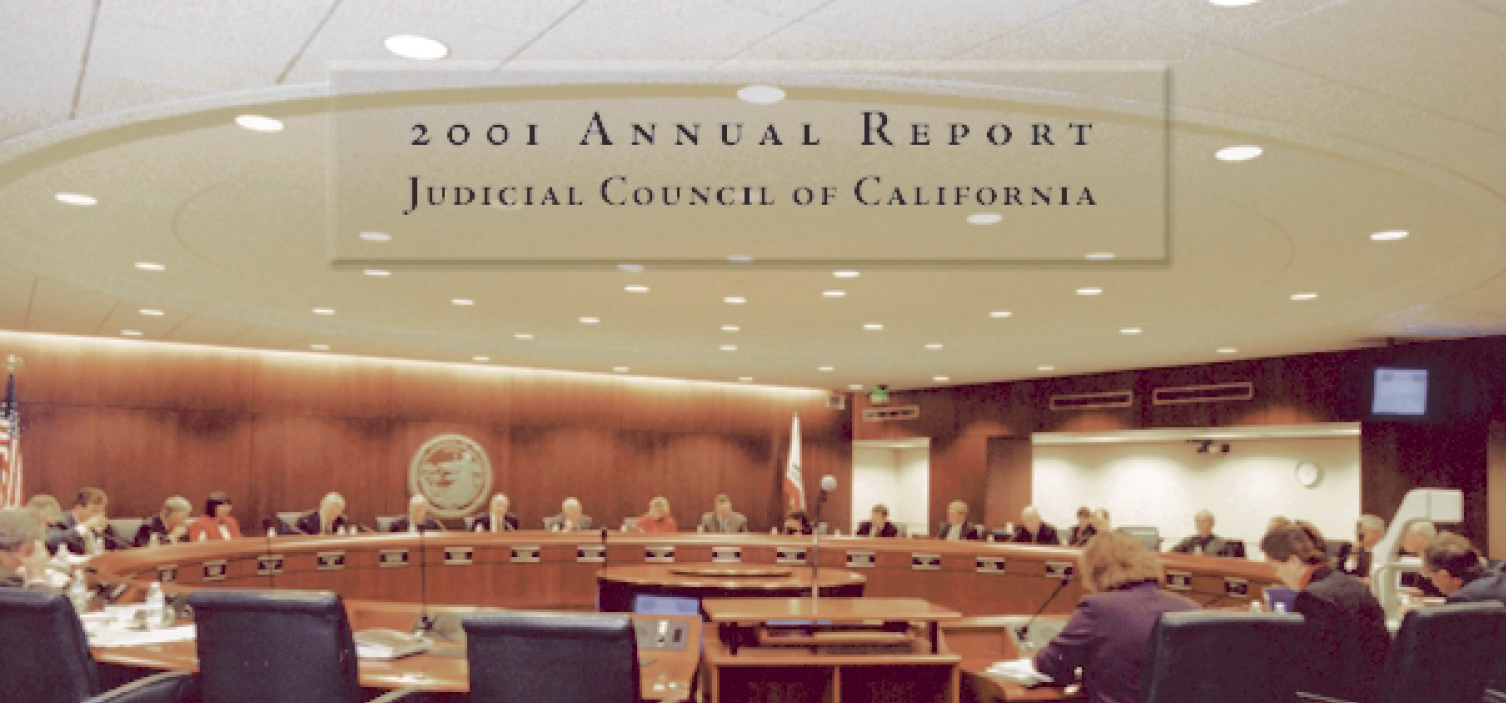

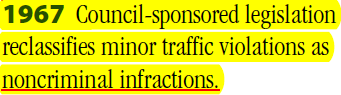

Both felonies and misdemeanors are jailable offenses, infractions are just a fine and you're not goin to jail, just takin what's in your wallet or purse and givin it to government employees who are supposed to know the rules they enforce. In fact infraction comprise the majority of so-called "traffic stops". That's what people call it when they get stopped but that's also a lie, it's an arrest but that's not part of this presentation.

Again, infractions make-up about 98% of all police contacts for Vehicle Code violations. Everyone should know that police and other law enforcement employees are prohibited from arresting anyone for NONcriminal conduct. Both citizens and law enforcement employees may arrest, however NO ONE is authorized to arrest anyone for NONcriminal behavior, so given a cop or CHP officer or Sheriff deputy stops people for infractions they must be crimes in order for their conduct to be legit otherwise they break the law. But what if they're not? Would the stop be valid? How could it be if what the law enforcement employee witnessed was not a crime? Would the word "Oooopse"apply? Well guess what?! Infractions are not crimes and there's only ONE court case in California history that contains those four words: "...infractions are not crimes...". That was determined by the California Court of Appeals in 1986 and has not gone up the the California Supreme Court nor to the federal Supreme Court for review. In other words it's "good law" or a correct ruling. So law enforcement employees are making unauthorized warrantless arrests for noncriminal commercial rule violations, and they're getting paid for it.

"...infractions are not crimes... ...the Legislature did not intend to classify infractions as crimes."

People v. Sava (1986) 190 Cal.App.3d 935.

People v. Sava (1986) 190 Cal.App.3d 935.

Who said crime doesn't pay?! Looks like the adults failed us again because every day Traffic Court is open lots and lots of people are paying for something that is not a crime yet the law enforcement employee actually broke the law and got paid for it.

NO MORE WARRANTLESS ARRESTS FOR NONCRIMINAL TRAFFIC (COMMERCE) INFRACTIONS!

COMMERCIAL

RULES DO NOT

APPLY TO NONCOMMERCIAL

CONDUCT

The

state has

the authority to regulate the use of public highways for business

purposes.

Morel v. Railroad Commission of California (1938) 11 Cal.2d 488

Morel v. Railroad Commission of California (1938) 11 Cal.2d 488

Which

in the case of that rat mobile it's probably a good idea they

do. Is there

ANY evidence that "driving" is job or occupation and the driver license

permits the issuee to qualify for a delivery job and be employed in the

transportation business in the capacity of driver? Is there

any evidence a motor vehicle is a tool used in the

transportation business?

CALIFORNIA PENAL CODE

§484d. As used in this section and Sections 484e to 484j, inclusive:

(9) "Traffic" means to transfer or otherwise dispose of property to another, or to obtain control of property

with intent to transfer or dispose of it to another.

§484d. As used in this section and Sections 484e to 484j, inclusive:

(9) "Traffic" means to transfer or otherwise dispose of property to another, or to obtain control of property

with intent to transfer or dispose of it to another.

CALIFORNIA PUBLIC UNITIES

CODE

§208. "Transportation of persons" includes every service in connection with or incidental to the safety, comfort, or convenience of the person transported and the receipt, carriage, and delivery of such person and his baggage.

§208. "Transportation of persons" includes every service in connection with or incidental to the safety, comfort, or convenience of the person transported and the receipt, carriage, and delivery of such person and his baggage.

- TOOLS OF THE TRADE -

TRAN$PORTATION $ERVICE

TAX BREAKS FOR THE RICH SO THEY CAN AFFORD THEIR ASTON MARTIN PAYMENTS

An

employee of a floral delivery

company. Obviously he’s a member of the

transportation department. His

presumptive job description is “driver”.

Feelin punked yet?

(1966)

That's

what's called "PUBLIC NOTICE".

The PUBLIC was NOTIFIED of a change to the law. They can not now claim they don't know.

The PUBLIC was NOTIFIED of a change to the law. They can not now claim they don't know.

Probable

cause does not require certain, positive information, or even enough to

convict someone. (Hart (2006 9th Cir.) 450 F.3d 1059,

1067.) Rather," [t]he standard of probable cause to

arrest

is the probability

of criminal activity, not a prima facie showing."

Charles C. (1999) 76 Cal.App.4th 420

Charles C. (1999) 76 Cal.App.4th 420

The

significance being, when it comes to so-called "traffic stops", people

are being subjected to a warrantless arrest. Law enforcement

employees are strictly prohibited from making false arrests.

Both the State legislators and Congress have seen fit to

limit the law enforcement officer's arrest

authority to crime. Arrests for noncriminal conduct

is a

crime (Cal.

Pen. Code §236)

Commercial or NONcommercial travel? The rules applicable to the former ARE NOT applicable to the latter.

Authorized warrantless arrest or NOT authorized warrantless arrest?

Class C driver license required

The primary device used, the primary tool used, the primary equipment used in the transportation business is the motor vehicle.

A MOTOR VEHICLE IS A DEVICE

(EQUIPMENT) USED FOR COMMERCIAL PURPO$E$

CALIFORNIA VEHICLE CODE

Commercial

Vehicle

260. (a)

A “commercial vehicle” is a motor vehicle of a type required to be

registered under this code used or maintained for the transportation of

persons for hire, compensation, or profit or designed, used, or

maintained primarily for the transportation of property.

(b) Passenger vehicles and house cars that are not used for the transportation of persons for hire, compensation, or profit are not commercial vehicles. This subdivision shall not apply to Chapter 4 (commencing with Section 6700) of Division 3.

415. (a) A "motor vehicle" is a vehicle...

670. A "vehicle" is a device...

(b) Passenger vehicles and house cars that are not used for the transportation of persons for hire, compensation, or profit are not commercial vehicles. This subdivision shall not apply to Chapter 4 (commencing with Section 6700) of Division 3.

415. (a) A "motor vehicle" is a vehicle...

670. A "vehicle" is a device...

A motor vehicle or vehicle is considered "goods". "Goods" is personal property or chattel as opposed to real property (dirt).

“So

long as one uses his private property for private purposes

and

does not devote it to the public use, the public has no interest in it

and no voice in its control.

ASSOCIATED

PIPE LINE COMPANY (a

Corporation) v. RAILROAD

COMMISSION OF THE STATE OF CALIFORNIA et al, (1917) 176 Cal.

518.

WEST'S

ANNOTATED

CALIFORNIA COMMERCIAL CODE

© 1990

CALIFORNIA COMMERCIAL CODE

© 1990

§9109. Classification of Goods: "Consumer goods"; "Equipment"; "Farm Products"; "Inventory"

Goods are

(1) "Consumer

goods" if

they are used or bought for use primarily for personal, family or

household purposes;

(2) "Equipment" if they are used or bought for the use primarily in business (including farming or a profession) or by a debtor who is a nonprofit organization or a government subdivision or agency or if the goods are not included in the definitions of inventory, farm products, or consumer goods.

(2) "Equipment" if they are used or bought for the use primarily in business (including farming or a profession) or by a debtor who is a nonprofit organization or a government subdivision or agency or if the goods are not included in the definitions of inventory, farm products, or consumer goods.

California

Code Comment

By John A. Bohn and Charles J. Williams

By John A. Bohn and Charles J. Williams

Prior California Law

1. The classification of goods in this section is new statutory law. The significance of this classification is described in Official Comment 1.

Although goods cannot belong to more than one category at any time, they may change their classification depending upon who holds them and for what reason. Each classification is mutually exclusive but the four classifications described are intended to include all goods.

Official Comment 2.

1. The classification of goods in this section is new statutory law. The significance of this classification is described in Official Comment 1.

Although goods cannot belong to more than one category at any time, they may change their classification depending upon who holds them and for what reason. Each classification is mutually exclusive but the four classifications described are intended to include all goods.

Official Comment 2.

REGISTRATION

OF THE DEVICE IS BASED

ON HOW IT'S USED

REGISTRATION

OF THE DEVICE IS BASED

ON HOW IT'S USED

"Thus

self-driven vehicles are classified according to the use to which they

are put rather than according to the means by which they are propelled."

Ex Parte Hoffert (1914) 34 S.D. 271, 148 N.W. 20

Ex Parte Hoffert (1914) 34 S.D. 271, 148 N.W. 20

CIVIL CODE CONSUMER GOODS

1791. As used in this chapter:

1791. As used in this chapter:

(a) "Consumer

goods" means any new product or part thereof that is used, bought, or

leased for use primarily for personal, family, or household purposes,

except for clothing and consumables. "Consumer

goods" shall

include new and used assistive devices sold at retail.

PUBLIC UTILITIES CODE

208.

"Transportation of persons" includes every service in connection with

or incidental to the safety, comfort, or convenience of the person

transported and the receipt, carriage, and delivery of such person and

his baggage.

209. "Transportation of property" includes every service in connection with or incidental to the transportation of property, including in particular its receipt, delivery, elevation, transfer, switching, carriage, ventilation, refrigeration, icing, dunnage, storage, and handling, and the transmission of credit by express corporations.

3950. It is a violation of law for any person or corporation to operate, or cause to be operated, on the highways of this state, any motor vehicle in the transportation of property or passengers for compensation in interstate commerce without having first complied with the requirements of this chapter. That violation may be prosecuted and punished as provided in Section 16560 of the Vehicle Code.

5108. "Motor vehicle" means every motor truck, tractor, or other self-propelled vehicle used for transportation of property over the public highways, otherwise than upon fixed rails or tracks, and any trailer, semitrailer, dolly, or other vehicle drawn thereby.

5110.5. With respect to a motor vehicle used in the transportation of property for compensation by a household goods carrier, "owner" means the corporation or person who is registered with the Department of Motor Vehicles as the owner of the vehicle, or who has a legal right to possession of the vehicle pursuant to a lease or rental agreement.

5352. The use of the public highways for the transportation of passengers for compensation is a business affected with a public interest. It is the purpose of this chapter to preserve for the public full benefit and use of public highways consistent with the needs of commerce without unnecessary congestion or wear and tear upon the highways; to secure to the people adequate and dependable transportation by carriers operating upon the highways; to secure full and unrestricted flow of traffic by motor carriers over the highways which will adequately meet reasonable public demands by providing for the regulation of all transportation agencies with respect to accident indemnity so that adequate and dependable service by all necessary transportation agencies shall be maintained and the full use of the highways preserved to the public; and to promote carrier and public safety through its safety enforcement regulations.

209. "Transportation of property" includes every service in connection with or incidental to the transportation of property, including in particular its receipt, delivery, elevation, transfer, switching, carriage, ventilation, refrigeration, icing, dunnage, storage, and handling, and the transmission of credit by express corporations.

3950. It is a violation of law for any person or corporation to operate, or cause to be operated, on the highways of this state, any motor vehicle in the transportation of property or passengers for compensation in interstate commerce without having first complied with the requirements of this chapter. That violation may be prosecuted and punished as provided in Section 16560 of the Vehicle Code.

5108. "Motor vehicle" means every motor truck, tractor, or other self-propelled vehicle used for transportation of property over the public highways, otherwise than upon fixed rails or tracks, and any trailer, semitrailer, dolly, or other vehicle drawn thereby.

5110.5. With respect to a motor vehicle used in the transportation of property for compensation by a household goods carrier, "owner" means the corporation or person who is registered with the Department of Motor Vehicles as the owner of the vehicle, or who has a legal right to possession of the vehicle pursuant to a lease or rental agreement.

5352. The use of the public highways for the transportation of passengers for compensation is a business affected with a public interest. It is the purpose of this chapter to preserve for the public full benefit and use of public highways consistent with the needs of commerce without unnecessary congestion or wear and tear upon the highways; to secure to the people adequate and dependable transportation by carriers operating upon the highways; to secure full and unrestricted flow of traffic by motor carriers over the highways which will adequately meet reasonable public demands by providing for the regulation of all transportation agencies with respect to accident indemnity so that adequate and dependable service by all necessary transportation agencies shall be maintained and the full use of the highways preserved to the public; and to promote carrier and public safety through its safety enforcement regulations.

The motor vehicle is to the transportation business what the shoe lace is to the shoe. It’s what flour is to bread.

The Department of Motor Vehicles regulates those employees in the transportation business who use a motor vehicle to perform their tasks, as well as regulating the motor vehicle itself. This is proper jurisdiction for this Department. This Department is a subagency of the CALIFORNIA STATE TRANSPORTATION AGENCY. It’s empowered to see to it that those using the streets and highways for business purposes know what they’re doing and their tools are in proper working order. This is germane to the primary role of the Legislature. They’re hired to ensure our clearly established constitutional rights and paramount unalienable interests are protected and defended. Someone who doesn’t know what they’re doing regarding their job in an industry regulated by the State government, could lead to personal and/or property damage which includes denial of clearly established constitutionally secured rights.

The

state has the authority to regulate the use of public highways for

bu$ine$$ purpo$e$.

Morel v. Railroad Commission of California (1938) 11 Cal.2d 488

Morel v. Railroad Commission of California (1938) 11 Cal.2d 488

Yeah, the plates say CA EXEMPT but they don’t say USED NONCOMMERCIALLY. Is it possible to have a device recognized by the State as exempt while still being used for a public or other commercial purpose?

There must have been a time when people wondered how they could tell the difference between someone using the streets for business from someone who doesn't.

Godfrey Daniels, we've got to come up with a plan!

PROBLEM

SOLVED: EVIDENCE of commerce. That which

distinguishes the

commercial from NONcommercial user of the streets and

highways.

Simple and efficient.

“A

carriage is peculiarly a family or household

article. It

contributes in a large degree to the health, convenience,

comfort and welfare of the householder or of the family”.

Arthur v. Morgan., 113 U.S. 495, 500, 5 S.Ct. 241, 243 (S.D.Ny 1884)

Automobile owned by individual not in business is ‘consumer goods’”.

In re Rave, 7 UCC rep. Serv 258

“An automobile purchased for personal and family use was ‘consumer goods’”.

Bank of Boston v. Jones, 4 UCC Rep. Serv. 1021, 236 A.2d. 484

“The use of an automobile by its owner for purposes of traveling to and from his work is a personal, as opposed to a business use as that term is defined in the California Commercial Code 9109(1), and the automobile will be classified as ‘consumer goods’ rather than equipment. The phraseology of §9102(2) defining goods used or bought for use primarily in business seems to contemplate a distinction between the collateral automobile ‘in business’ and the mere use of the collateral automobile for some commercial, economic or income producing purpose by one not engaged in ‘business’”.

In re Barnes 11 USS rep. Serv. 697 (1972)

“Under the UCC §9-109 there is a real distinction between goods purchased for personal use and those purchase for business use. The two are mutually exclusive and the principal use to which the property is put should be considered as determinative”.

James Talcott, Inc. v. Gee, 5 UCC rep. Serv. 1028, 266 Cal.App.2d. 384, 72 Cal.Reptr. (1968).

“The use to which an item is put rather than its physical characteristics determine whether it should be classified as ‘consumer goods’ under UCC §9-109(1) or ‘equipment’ under UCC §9-109(2)”.

Grimes v. Massey Ferguson, Inc., 23 UCC Rep. Serv. 655, 355 So. 2d. 338 (Ala., 1978)

“The classification of goods in UCC §9-109 are mutually exclusive”.

McFadden v. Mercantile-Safe Deposit & Trust Co., 8 UCC Rep. Serv. 766, 260 Md. 601, 273, A.2d. 198 (1971)

“The term ‘household goods’..includes everything about the house that is usually held and enjoyed therewith and that tends to the comfort and accommodation of the household”.

Lawwill v. Lawwill, 515 P.2d. 900, 903, 21 Ariz.App.75 , 19A Words and Phrases - Permanent Edition (West) pocket part 94

“Automobile purchased for the purpose of transporting buyer to and from his place of employment was ‘consumer goods’ as defined in UCC §9-109".

Mallicoat v. Volunteer Finance & Loan Corp., 3 UCC Rep. Serv. 1035, 415 S.W.2d. 347 (Tenn.App., 1966)

A classification of motor vehicles, based on whether they are used for business or commercial purposes, or merely kept for pleasure or family use, a license fee being imposed in one case and not in the other, is a proper one.

Ohio - Fisher Bros. Co. v. Brown, 146 N.E. 100, III Ohio St. 602.

"This law does not impose tax on motor vehicles and motor-cycles as property, nor is it a tax on the person for the ownership of the vehicle. It is a tax on the privilege of using the vehicle upon the public roads. It is in the nature of a toll for the use of the highway. Not the vehicle, but the privilege of using the vehicle, is taxed.

State v. Lawrence (1914), 108 Miss. 291

Automobile is the generic name which has been adopted by popular approval for all forms of self-propelling vehicles for use upon highways and streets for general freight and passenger service.

"The word 'automobile' has a well-fixed significance in the popular understanding. It is understood to refer to a wheeled vehicle, propelled by gasoline, steam, or electricity, and used for the transportation of persons and merchandise."

"An automobile may be defined as a wheeled vehicle, propelled by steam, electricity, or gasoline, and used for the transportation of persons or merchandise. The courts, without making clear distinctions, have generally used the terms automobile, motor vehicle, motor car,...

THE LAW OF AUTOMOBILES, by C. P. BERRY of the ST. LOUIS BAR, 3rd Ed., 1921, p. 2

The word "vehicle" means any carriage moving on wheels or runners used, or capable of being

used, as a means of transportation on land. 35

35. Vehicle defined: "The word 'vehicle' includes every description of carriage or other artificial contrivance used, or capable of being used, as a means of transportation on land." U. S. Comp.

St. 1901, p. 4; Anderson's Law Diet., tit."Vehicle;" Black's Law Diet., tit. "Vehicle;" Bouvier's Law Diet., tit. "Vehicle."

A vehicle is "any carriage moving on land, either on wheels or on runners."

Cent. Diet., tit. "Vehicle."

"Vehicle: That in which anything is or may be carried, as a coach, wagon, cart, carriage, or the like." Webster's Diet., tit. "Vehicle."

"A vehicle is any carriage moving on land, either on wheels or runners; a conveyance ; that which is used as an instrument of conveyance, transportation or communication." Davis v. Petrinovich, 112 Ala. 654, 21 So. 354, 36 L. R. A. 615.

A sprinkling cart is a vehicle. St. Louis v. Woodruff, 71 Mo. 92.

An electric street car is a vehicle. Foster v. Curtis, 213 Mass. 79, 99 N. E. 961,

Ann. Cas. 1913E 1116 (1912).

Id. p. 22

Thus an automobile used for hire in the District of Columbia, for which the owner has a public hack license, is a vehicle within the meaning of a police regulation which provides that vehicles for hire, seeking employment, shall not loiter on the streets, except at the regular public stands. But it was decided in another case in the District of Columbia, that an electric automobile, though a carriage, does not belong to the classes of vehicles made the subjects of license tax by an act imposing a tax on the proprietors of hacks, cabs, omnibuses, and other vehicles for the transportation of passengers for hire,...

id. p. 23

It is a rule of construction, little less old than construction itself, that penal statutes, that is, statutes which impose a penalty for their violation, must be strictly construed as against the state and in favor of the accused.

Id., p. 44

Given

those court citations, are those of us not using our property for

any commercial purpose exempt from having a license and registering our

property?comfort and welfare of the householder or of the family”.

Arthur v. Morgan., 113 U.S. 495, 500, 5 S.Ct. 241, 243 (S.D.Ny 1884)

Automobile owned by individual not in business is ‘consumer goods’”.

In re Rave, 7 UCC rep. Serv 258

“An automobile purchased for personal and family use was ‘consumer goods’”.

Bank of Boston v. Jones, 4 UCC Rep. Serv. 1021, 236 A.2d. 484

“The use of an automobile by its owner for purposes of traveling to and from his work is a personal, as opposed to a business use as that term is defined in the California Commercial Code 9109(1), and the automobile will be classified as ‘consumer goods’ rather than equipment. The phraseology of §9102(2) defining goods used or bought for use primarily in business seems to contemplate a distinction between the collateral automobile ‘in business’ and the mere use of the collateral automobile for some commercial, economic or income producing purpose by one not engaged in ‘business’”.

In re Barnes 11 USS rep. Serv. 697 (1972)

“Under the UCC §9-109 there is a real distinction between goods purchased for personal use and those purchase for business use. The two are mutually exclusive and the principal use to which the property is put should be considered as determinative”.

James Talcott, Inc. v. Gee, 5 UCC rep. Serv. 1028, 266 Cal.App.2d. 384, 72 Cal.Reptr. (1968).

“The use to which an item is put rather than its physical characteristics determine whether it should be classified as ‘consumer goods’ under UCC §9-109(1) or ‘equipment’ under UCC §9-109(2)”.

Grimes v. Massey Ferguson, Inc., 23 UCC Rep. Serv. 655, 355 So. 2d. 338 (Ala., 1978)

“The classification of goods in UCC §9-109 are mutually exclusive”.

McFadden v. Mercantile-Safe Deposit & Trust Co., 8 UCC Rep. Serv. 766, 260 Md. 601, 273, A.2d. 198 (1971)

“The term ‘household goods’..includes everything about the house that is usually held and enjoyed therewith and that tends to the comfort and accommodation of the household”.

Lawwill v. Lawwill, 515 P.2d. 900, 903, 21 Ariz.App.75 , 19A Words and Phrases - Permanent Edition (West) pocket part 94

“Automobile purchased for the purpose of transporting buyer to and from his place of employment was ‘consumer goods’ as defined in UCC §9-109".

Mallicoat v. Volunteer Finance & Loan Corp., 3 UCC Rep. Serv. 1035, 415 S.W.2d. 347 (Tenn.App., 1966)

A classification of motor vehicles, based on whether they are used for business or commercial purposes, or merely kept for pleasure or family use, a license fee being imposed in one case and not in the other, is a proper one.

Ohio - Fisher Bros. Co. v. Brown, 146 N.E. 100, III Ohio St. 602.

"This law does not impose tax on motor vehicles and motor-cycles as property, nor is it a tax on the person for the ownership of the vehicle. It is a tax on the privilege of using the vehicle upon the public roads. It is in the nature of a toll for the use of the highway. Not the vehicle, but the privilege of using the vehicle, is taxed.

State v. Lawrence (1914), 108 Miss. 291

Automobile is the generic name which has been adopted by popular approval for all forms of self-propelling vehicles for use upon highways and streets for general freight and passenger service.

"The word 'automobile' has a well-fixed significance in the popular understanding. It is understood to refer to a wheeled vehicle, propelled by gasoline, steam, or electricity, and used for the transportation of persons and merchandise."

"An automobile may be defined as a wheeled vehicle, propelled by steam, electricity, or gasoline, and used for the transportation of persons or merchandise. The courts, without making clear distinctions, have generally used the terms automobile, motor vehicle, motor car,...

THE LAW OF AUTOMOBILES, by C. P. BERRY of the ST. LOUIS BAR, 3rd Ed., 1921, p. 2

The word "vehicle" means any carriage moving on wheels or runners used, or capable of being

used, as a means of transportation on land. 35

35. Vehicle defined: "The word 'vehicle' includes every description of carriage or other artificial contrivance used, or capable of being used, as a means of transportation on land." U. S. Comp.

St. 1901, p. 4; Anderson's Law Diet., tit."Vehicle;" Black's Law Diet., tit. "Vehicle;" Bouvier's Law Diet., tit. "Vehicle."

A vehicle is "any carriage moving on land, either on wheels or on runners."

Cent. Diet., tit. "Vehicle."

"Vehicle: That in which anything is or may be carried, as a coach, wagon, cart, carriage, or the like." Webster's Diet., tit. "Vehicle."

"A vehicle is any carriage moving on land, either on wheels or runners; a conveyance ; that which is used as an instrument of conveyance, transportation or communication." Davis v. Petrinovich, 112 Ala. 654, 21 So. 354, 36 L. R. A. 615.

A sprinkling cart is a vehicle. St. Louis v. Woodruff, 71 Mo. 92.

An electric street car is a vehicle. Foster v. Curtis, 213 Mass. 79, 99 N. E. 961,

Ann. Cas. 1913E 1116 (1912).

Id. p. 22

Thus an automobile used for hire in the District of Columbia, for which the owner has a public hack license, is a vehicle within the meaning of a police regulation which provides that vehicles for hire, seeking employment, shall not loiter on the streets, except at the regular public stands. But it was decided in another case in the District of Columbia, that an electric automobile, though a carriage, does not belong to the classes of vehicles made the subjects of license tax by an act imposing a tax on the proprietors of hacks, cabs, omnibuses, and other vehicles for the transportation of passengers for hire,...

id. p. 23

It is a rule of construction, little less old than construction itself, that penal statutes, that is, statutes which impose a penalty for their violation, must be strictly construed as against the state and in favor of the accused.

Id., p. 44

...named

Catalla

CATALLA.

In old English law. Chattels. The word

among the

Normans primarily signified only beasts of husbandry, or, as they are

still called, "cattle," but, in a secondary sense, the term was applied

to all movables in general, and not only to these, but to whatever was

not a fief or feud.

Wharton.

Catalla juste possasea amitti non posunt.

Chattels justly possessed caunot be lost.

Jenk. Cent. 28.

Wharton.

Catalla juste possasea amitti non posunt.

Chattels justly possessed caunot be lost.

Jenk. Cent. 28.

IMPOUND

= TAKING A CAR AWAY

CEPIT ET ABDUXIT.

He took and led away. The emphatic words in writs

in

trespass or indictments for larceny, where the thing taken was a living

chattel, i. 6., an animal.

CEPIT ET ASPORTAVIT. He took and carried away. Applicable in a declaration in trespass or an indictment for larceny where the defendant has carried away goods without right. 4 Bl. Comm. 23l.

CEPIT IN ALIO LOCO. In pleading. A plea in replevin, by which the defendant alleges that he took the thing replevied in another place than that mentioned in the declaration. 1 Chit. Pl. 490.

CHATTEL. An article of personal property; any species of property not amounting to a freehold or fee in land. The name given to things which in law are deemed personal property. Chattels are divided into chattels real and chattels personal; chattle real being interests in land which devolve after the manner of personal estate, as leaseholds. As opposed to freeholds, they are regarded as personal estate. But, as being interests in real estate, they are called "chattels real," to distinguish them from movables, which are called "chattels personal." Mozley & Whitley.

Chattels personal are movables only; chattels real are such as savor only of the realty. 19 Johns. 73.

The term "chattels" is a a more comprehensive one than "goods", as it includes animate as well as inanimate property. 2 Chit. Bl. Comm. 383, note. In a devise, however, they seem to be of the same import. Shep. Touch. 447 ; 2 Fonbl Eq. 335.

p. 197

CHEMIN. The road wherein every man goes; the king's high way.

p. 200

CHIMIN. In old English law. A road, way, highway. It is either the queen's highway (chiminus regina:) or a private way. The first is that over which the subjects of the realm, and all others under the protection of the crown, have free liberty to pass, though the property in the soil itself belong to some private individual; the last is that in which one person or more have liberty to pass over the land of another, by prescription or charter. Warton.

p. 200, 201

CHIMINUS. The way by which the king and all his subjects and all under his protection had a right to pass, though the property of the soil of each side where the way may belong to a private man. Cowell.

p. 201

The previous terms are from Black's Law Dictionary, 1st Edition, DOWNLOAD

CEPIT ET ASPORTAVIT. He took and carried away. Applicable in a declaration in trespass or an indictment for larceny where the defendant has carried away goods without right. 4 Bl. Comm. 23l.

CEPIT IN ALIO LOCO. In pleading. A plea in replevin, by which the defendant alleges that he took the thing replevied in another place than that mentioned in the declaration. 1 Chit. Pl. 490.

CHATTEL. An article of personal property; any species of property not amounting to a freehold or fee in land. The name given to things which in law are deemed personal property. Chattels are divided into chattels real and chattels personal; chattle real being interests in land which devolve after the manner of personal estate, as leaseholds. As opposed to freeholds, they are regarded as personal estate. But, as being interests in real estate, they are called "chattels real," to distinguish them from movables, which are called "chattels personal." Mozley & Whitley.

Chattels personal are movables only; chattels real are such as savor only of the realty. 19 Johns. 73.

The term "chattels" is a a more comprehensive one than "goods", as it includes animate as well as inanimate property. 2 Chit. Bl. Comm. 383, note. In a devise, however, they seem to be of the same import. Shep. Touch. 447 ; 2 Fonbl Eq. 335.

p. 197

CHEMIN. The road wherein every man goes; the king's high way.

p. 200

CHIMIN. In old English law. A road, way, highway. It is either the queen's highway (chiminus regina:) or a private way. The first is that over which the subjects of the realm, and all others under the protection of the crown, have free liberty to pass, though the property in the soil itself belong to some private individual; the last is that in which one person or more have liberty to pass over the land of another, by prescription or charter. Warton.

p. 200, 201

CHIMINUS. The way by which the king and all his subjects and all under his protection had a right to pass, though the property of the soil of each side where the way may belong to a private man. Cowell.

p. 201

The previous terms are from Black's Law Dictionary, 1st Edition, DOWNLOAD

COERCION.

Compulsion; force; duress. It may be either actual, (direct or

positive,) where physical force fa put upon a man to compel him to do

an act against hie will, or implied,

(legal or constructive.) where the relation of the parties is such that

one is under subjection to the other, and is thereby constrained to do

what his free will would refuse.

p. 216, 217

p. 216, 217

The "police power" is applicable to COMMERCIAL CONDUCT.

1.

LICENSES (§ 5*) - CHAUFFEURS.

The occupation of a chauffeur is one calling for regulation and therefore permitting a regulatory license tax.

[Ed. Note. - For other cases, see licenses, Cent. Dig §§4, 19; dec. Dig. § 5*]

2. STATUTES (§ 81*) - SPECIAL LEGISLATION - CLASSIFICATION.

The occupation of a chauffeur is one calling for regulation and therefore permitting a regulatory license tax.

[Ed. Note. - For other cases, see licenses, Cent. Dig §§4, 19; dec. Dig. § 5*]

2. STATUTES (§ 81*) - SPECIAL LEGISLATION - CLASSIFICATION.

Dividing,

as does St. 1913, p. 639, drivers of automobiles into two classes, one

professional chauffeurs, and requiring them to obtain a license, and

pay an annual fee of $2, the other embracing all others, who are not

required to secure a license or pay a license fee, is sound

classification and not arbitrary, so as to constitute special

legislation.

Ex parte Stork, 167 Cal. 294 (Supreme Court of California. Feb. 24, 1914)

Ex parte Stork, 167 Cal. 294 (Supreme Court of California. Feb. 24, 1914)

And former section 9109*, in classifying goods, provides: "Goods are (1) 'consumer goods' if they are used or bought for use primarily for personal, family or household purposes; (2) 'equipment' if they are used or bought for use primarily in business. ..." It is not without [266 Cal.App.2d 388] significance that the definition of goods in the Unruh Act parallels the definition of consumer goods in the Commercial Code.

* The Legislature has modified that section. Notwithstanding what's presently there, the definitions, regardless of their current locations, have not changed.

[3]

Thus, there is a

real distinction between goods purchased for personal use and goods

purchased for business use. The two are mutually

exclusive,

and the principal use to which the property is put should be considered

as determinative.

James Talcott, Inc. v. Gee , 266 Cal.App.2d 384

[Civ. No. 31802. Second Dist., Div. Five. Oct. 4, 1968.]

James Talcott, Inc. v. Gee , 266 Cal.App.2d 384

[Civ. No. 31802. Second Dist., Div. Five. Oct. 4, 1968.]

It should be apparent by now that we’ve been mislead in a very big way. That misleading constitutes fraud. I posit that people have been subject to fraud which lead to their decision to go to the DMV and ask for permission to do something they had no intention of doing. The State has benefited from the fraud perpetrated by everyone that you can’t go anywhere for any reason in a car, truck, van, or motor cycle without a license, without government employee’s permission and paying for the permission first.

Title 37, American Jurisprudence

2d at section 8 states, in part:

"Fraud vitiates every transaction and all contracts. Indeed, the principle is often stated, in broad and sweeping language, that fraud destroys the validity of everything into which it enters, and that it vitiates the most solemn contracts, documents, and even judgments."

Vitiate

To impair or make void; to destroy or annul, either completely or partially, the force and effect of an act or instrument.

Mutual mistake or Fraud, for example, might vitiate a contract.

West's Encyclopedia of American Law, edition 2. Copyright 2008 The Gale Group, Inc. All rights reserved.

vitiate - verb abolish, abrogate, annul, blight, cancel, counteract, damage, depravare, destroy, disannul, impair, injure, invalidate, make faulty, make imperfect, make immure, make ineffective, make void, mar, negate, negative, neutralize, nullify, overturn, pervert, poison, pollute, quash, render defective, render inefficacious, rescind, reverse, spoil, sully, tamper with, undo, vitiare, weaken

Foreign phrases: Crimen omnia ex se nata vitiat. Crime vitiates all that is born of it.

Title 42, CODE OF FEDERAL REGULATIONS, Ch. IV, Subchapter C, Part 455, Section 455.2 - Definitions.

"Fraud vitiates every transaction and all contracts. Indeed, the principle is often stated, in broad and sweeping language, that fraud destroys the validity of everything into which it enters, and that it vitiates the most solemn contracts, documents, and even judgments."

Vitiate

To impair or make void; to destroy or annul, either completely or partially, the force and effect of an act or instrument.

Mutual mistake or Fraud, for example, might vitiate a contract.

West's Encyclopedia of American Law, edition 2. Copyright 2008 The Gale Group, Inc. All rights reserved.

vitiate - verb abolish, abrogate, annul, blight, cancel, counteract, damage, depravare, destroy, disannul, impair, injure, invalidate, make faulty, make imperfect, make immure, make ineffective, make void, mar, negate, negative, neutralize, nullify, overturn, pervert, poison, pollute, quash, render defective, render inefficacious, rescind, reverse, spoil, sully, tamper with, undo, vitiare, weaken

Foreign phrases: Crimen omnia ex se nata vitiat. Crime vitiates all that is born of it.

Title 42, CODE OF FEDERAL REGULATIONS, Ch. IV, Subchapter C, Part 455, Section 455.2 - Definitions.

§ 455.2 Definitions.

As

used in this part unless the context indicates otherwise—

Abuse means provider practices that are inconsistent with sound fiscal, business, or medical practices, and result in an unnecessary cost to the Medicaid program, or in reimbursement for services that are not medically necessary or that fail to meet professionally recognized standards for health care. It also includes beneficiary practices that result in unnecessary cost to the Medicaid program.

Conviction or Convicted means that a judgment of conviction has been entered by a Federal, State, or local court, regardless of whether an appeal from that judgment is pending.

Credible allegation of fraud. A credible allegation of fraud may be an allegation, which has been verified by the State, from any source, including but not limited to the following:

Exclusion means that items or services furnished by a specific provider who has defrauded or abused the Medicaid program will not be reimbursed under Medicaid.

Fraud means an intentional deception or misrepresentation made by a person with the knowledge that the deception could result in some unauthorized benefit to himself or some other person. It includes any act that constitutes fraud under applicable Federal or State law.

Furnished refers to items and services provided directly by, or under the direct supervision of, or ordered by, a practitioner or other individual (either as an employee or in his or her own capacity), a provider, or other supplier of services. (For purposes of denial of reimbursement within this part, it does not refer to services ordered by one party but billed for and provided by or under the supervision of another.)

Practitioner means a physician or other individual licensed under State law to practice his or her profession.

Suspension means that items or services furnished by a specified provider who has been convicted of a program-related offense in a Federal, State, or local court will not be reimbursed under Medicaid. [48 FR 3755, Jan. 27, 1983, as amended at 50 FR 37375, Sept. 13, 1985; 51 FR 34788, Sept. 30, 1986; 76 FR 5965, Feb. 2, 2011]

Abuse means provider practices that are inconsistent with sound fiscal, business, or medical practices, and result in an unnecessary cost to the Medicaid program, or in reimbursement for services that are not medically necessary or that fail to meet professionally recognized standards for health care. It also includes beneficiary practices that result in unnecessary cost to the Medicaid program.

Conviction or Convicted means that a judgment of conviction has been entered by a Federal, State, or local court, regardless of whether an appeal from that judgment is pending.

Credible allegation of fraud. A credible allegation of fraud may be an allegation, which has been verified by the State, from any source, including but not limited to the following:

(1) Fraud hotline complaints.

(2) Claims data mining.

(3) Patterns identified through provider audits, civil false claims cases, and law enforcement investigations. Allegations are considered to be credible when they have indicia of reliability and the State Medicaid agency has reviewed all allegations, facts, and evidence carefully and acts judiciously on a case-by-case basis.

(2) Claims data mining.

(3) Patterns identified through provider audits, civil false claims cases, and law enforcement investigations. Allegations are considered to be credible when they have indicia of reliability and the State Medicaid agency has reviewed all allegations, facts, and evidence carefully and acts judiciously on a case-by-case basis.

Exclusion means that items or services furnished by a specific provider who has defrauded or abused the Medicaid program will not be reimbursed under Medicaid.

Fraud means an intentional deception or misrepresentation made by a person with the knowledge that the deception could result in some unauthorized benefit to himself or some other person. It includes any act that constitutes fraud under applicable Federal or State law.

Furnished refers to items and services provided directly by, or under the direct supervision of, or ordered by, a practitioner or other individual (either as an employee or in his or her own capacity), a provider, or other supplier of services. (For purposes of denial of reimbursement within this part, it does not refer to services ordered by one party but billed for and provided by or under the supervision of another.)

Practitioner means a physician or other individual licensed under State law to practice his or her profession.

Suspension means that items or services furnished by a specified provider who has been convicted of a program-related offense in a Federal, State, or local court will not be reimbursed under Medicaid. [48 FR 3755, Jan. 27, 1983, as amended at 50 FR 37375, Sept. 13, 1985; 51 FR 34788, Sept. 30, 1986; 76 FR 5965, Feb. 2, 2011]

JURISDICTION

the power to hear and determine a case. 147 P.2d 759,

761.

This power may be established and described with reference to

particular subjects or to parties who fall into a particular

category. In addition to the power to adjudicate, a

valid

exercise of jurisdiction requires fair notice and an opportunity for

the affected parties to be heard. Without

jurisdiction, a

court's judgment is void. A court must have both

SUBJECT

MATTER JURISDICTION and PERSONAL JURISDICTION (see below).

See

also territorial jurisdiction; title jurisdiction."

SUBJECT MATTER JURISDICTION refers to the competency of the court to hear and determine a particular category of cases. Federal district courts have "limited" jurisdiction in that they have only such jurisdiction as is explicitly conferred by federal statutes. 28 U.S.C. §1330 [EDITOR'S NOTE: see also 40 U.S.C.S. §255] et seq. See LIMITED [SPECIAL] JURISDICTION. Many state trial courts have "general" jurisdiction to hear almost all matters. The parties to a lawsuit may not waive a requirement of subject matter jurisdiction.

TERRITORIAL JURISDICTION the territory over which a government or a subdivision thereof has jurisdiction, 147 P.2d 858, 861; relates to a tribunal's power with regard to the territory within which it is to be exercised, and connotes power over property and persons within such territory. 94 N.E. 2d 438, 440.

A court cannot lift itself by its own bootstraps, i.e., it cannot acquire jurisdiction by a declaration that it has jurisdiction.

CALIFORNIA PROCEDURE, Second Edition, by B. E. WITKIN, Volume, 3(a) §232

SUBJECT MATTER JURISDICTION refers to the competency of the court to hear and determine a particular category of cases. Federal district courts have "limited" jurisdiction in that they have only such jurisdiction as is explicitly conferred by federal statutes. 28 U.S.C. §1330 [EDITOR'S NOTE: see also 40 U.S.C.S. §255] et seq. See LIMITED [SPECIAL] JURISDICTION. Many state trial courts have "general" jurisdiction to hear almost all matters. The parties to a lawsuit may not waive a requirement of subject matter jurisdiction.

TERRITORIAL JURISDICTION the territory over which a government or a subdivision thereof has jurisdiction, 147 P.2d 858, 861; relates to a tribunal's power with regard to the territory within which it is to be exercised, and connotes power over property and persons within such territory. 94 N.E. 2d 438, 440.

A court cannot lift itself by its own bootstraps, i.e., it cannot acquire jurisdiction by a declaration that it has jurisdiction.

CALIFORNIA PROCEDURE, Second Edition, by B. E. WITKIN, Volume, 3(a) §232

How does the Traffic Court acquire jurisdiction to adjudicate a traffic matter?

1. The topic.

2. A complaint.

3. A legitimate arrest.

4. You being the subject to the rule allegedly violated.

2. A complaint.

3. A legitimate arrest.

4. You being the subject to the rule allegedly violated.

Let’s take No. 1, the TOPIC. Traffic Court deals with TRAFFIC grievances. Obviously the TRAFFIC COURT deals with violations of rules that apply to TRAFFIC and TRAFFIC regulation. The question then becomes, WHAT’S TRAFFIC?

TRAFFIC.

Commerce; trade; sale or exchange of merchandise, bills, money, and the

like. The passing of goods or commodities from one

person

to another for an equivalent in goods or money. Senior v.

Ratterman, 44 Ohio St. 673, 11 N.E. 321; Fine v. Moran, 74 Fla. 417, 77

So. 533, 538; Bruno v. U.S., C.C.A.Mass., 289 F. 649, 655; Kroger

Grocery and Baking Co. V. Schwer, 36 Ohio App. 512, 173 N.E.

633. The subjects of transportation on a route, as

persons

or goods; the passing to and fro of persons, animals, vehicles, or

vessels, along a route of transportation, as a long a street, canal

etc. United States v. Golden Gate Bridge and Highway Dist. of

California , D.C.Cal., 37 F. Supp. 505, 512.

Black’s Law Dictionary, 4th Ed., p. 1667

COMMERCIAL. Relating to or connected with trade and traffic or commerce in general. “Zante Currents”, C.C.Cal.,73 F. 189. Occupied with commerce. Bowles v. Co-Operative G. L. F. Farm Products, D.C.N.Y., 53 F. Supp. 413, 415.

Black’s Law Dictionary, 4th Ed., p. 337

INTERSTATE COMMERCE. Traffic, intercourse, commercial trading, or the transportation of persons or property between or among the several states of the Union, or from between points in one state and points in another state; commerce between the states, or between places in different states. It comprehends all the component parts of commercial intercourse between different states. [Cites omitted]

Black’s Law Dictionary, 4th Ed., p. 955

Traffic - Webster's Unified Dictionary and Encyclopedia, International Illustrated Edition (1960)

1. Business or trade, commerce. 2. Transportation. 3. The movement of vehicles on street or highway, as, the traffic is very heavy today.

Traffic - Bouvier's Law Dictionary (1856)

Commerce, trade, sale or exchange of merchandise, bills, money and the like.

Traffic - Black's Law Dictionary 3rd. Ed

Commerce; trade; sale or exchange of merchandise, bills, money, and the like. The passing of goods or commodities from one person to another for an equivalent in goods or money. Senior v. Ratterman, 44 Ohio St. 673, 11 N.E. 321; People v. Horan, 293 Ill. 314, 127 N.E. 673, 674; People v. Dunford, 207 N.Y. 17, 100 N.E. 433, 434; Fine v. Morgan, 74 Fla. 417, 77 So. 533, 538; Bruno v. U. S. (C.C.A.) 289 F. 649, 655. Traffic includes the ordinary uses of the streets and highways by travelers. Stewart v. Hugh Nawn Contracting Co., 223 Mass. 525, 112 N.E. 218, 219; Withey v. Fowler Co., 164 Iowa, 377, 145 N.W. 923, 927.

Traffic - Black's Law Dictionary 6th. Ed

Commerce; trade; sale or exchange of merchandise, bills, money, and the like. The passing or exchange of goods or commodities from one person to another for an equivalent in goods and money. The subjects of transportation on a route, as persons or goods; the passing to and fro of persons, animals, vegetables, or vessels, along a route of transportation, as along a street, highway, etc.

Traffic - Florida Words & Phrases

(See Fine v. Moran, 77 So. 533, 538)

Black’s Law Dictionary, 4th Ed., p. 1667

COMMERCIAL. Relating to or connected with trade and traffic or commerce in general. “Zante Currents”, C.C.Cal.,73 F. 189. Occupied with commerce. Bowles v. Co-Operative G. L. F. Farm Products, D.C.N.Y., 53 F. Supp. 413, 415.

Black’s Law Dictionary, 4th Ed., p. 337

INTERSTATE COMMERCE. Traffic, intercourse, commercial trading, or the transportation of persons or property between or among the several states of the Union, or from between points in one state and points in another state; commerce between the states, or between places in different states. It comprehends all the component parts of commercial intercourse between different states. [Cites omitted]

Black’s Law Dictionary, 4th Ed., p. 955

Traffic - Webster's Unified Dictionary and Encyclopedia, International Illustrated Edition (1960)

1. Business or trade, commerce. 2. Transportation. 3. The movement of vehicles on street or highway, as, the traffic is very heavy today.

Traffic - Bouvier's Law Dictionary (1856)

Commerce, trade, sale or exchange of merchandise, bills, money and the like.

Traffic - Black's Law Dictionary 3rd. Ed

Commerce; trade; sale or exchange of merchandise, bills, money, and the like. The passing of goods or commodities from one person to another for an equivalent in goods or money. Senior v. Ratterman, 44 Ohio St. 673, 11 N.E. 321; People v. Horan, 293 Ill. 314, 127 N.E. 673, 674; People v. Dunford, 207 N.Y. 17, 100 N.E. 433, 434; Fine v. Morgan, 74 Fla. 417, 77 So. 533, 538; Bruno v. U. S. (C.C.A.) 289 F. 649, 655. Traffic includes the ordinary uses of the streets and highways by travelers. Stewart v. Hugh Nawn Contracting Co., 223 Mass. 525, 112 N.E. 218, 219; Withey v. Fowler Co., 164 Iowa, 377, 145 N.W. 923, 927.

Traffic - Black's Law Dictionary 6th. Ed

Commerce; trade; sale or exchange of merchandise, bills, money, and the like. The passing or exchange of goods or commodities from one person to another for an equivalent in goods and money. The subjects of transportation on a route, as persons or goods; the passing to and fro of persons, animals, vegetables, or vessels, along a route of transportation, as along a street, highway, etc.

Traffic - Florida Words & Phrases

(See Fine v. Moran, 77 So. 533, 538)

QUIT ASKIN QUESTIONS PUNK AND COUGH UP THE DOUGH!

THE CALIFORNIA LEGISLATURE

HARD AT WORK PROTECTING AND DEFENDING

OUR CLEARLY ESTABLISHED CONSTITUTIONALLY SECURED RIGHTS

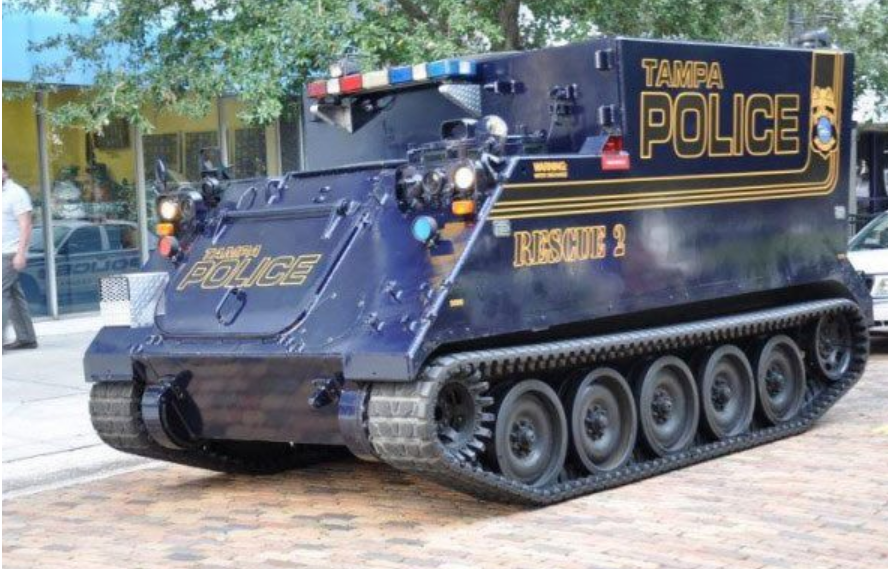

HEY

TAX PAYERS, LOOKIE ALL THAT COOL SHIT YOU OWN!

THESE

GUYS GET YA COMIN AND GOIN. FIRST THEY STOP YOU

(AND YOU

HAVE NO CHOICE ABOUT THAT), THEN YOU GET BILLED, THEN THEY BUY

THAT KINDA STUFF, BUT IT'S ACTUALLY YOURS! HOW MANY OF THOSE

POSER G.I. JOES ACTUALLY KNOW THAT?

THE

GUY WITH NO SHIRT IS HOMELESS AND THEY JUST WOKE

HIM UP WHILE HE WAS STAYING A PLACE FOR HOMELESS PEOPLE

HIM UP WHILE HE WAS STAYING A PLACE FOR HOMELESS PEOPLE

MISBEHAVING STUDENTS GET THEIR JUST DESERTS FOR HAVING THE GALL

TO EXERCISE THEIR CLEARLY ESTABLISHED CONSTITUTIONALLY SECURED RIGHTS

Everyone knows you

CAN NOT exercise any clearly established constitutionally secured

rights

unless you finish skool, NOT DROP OUT!

unless you finish skool, NOT DROP OUT!

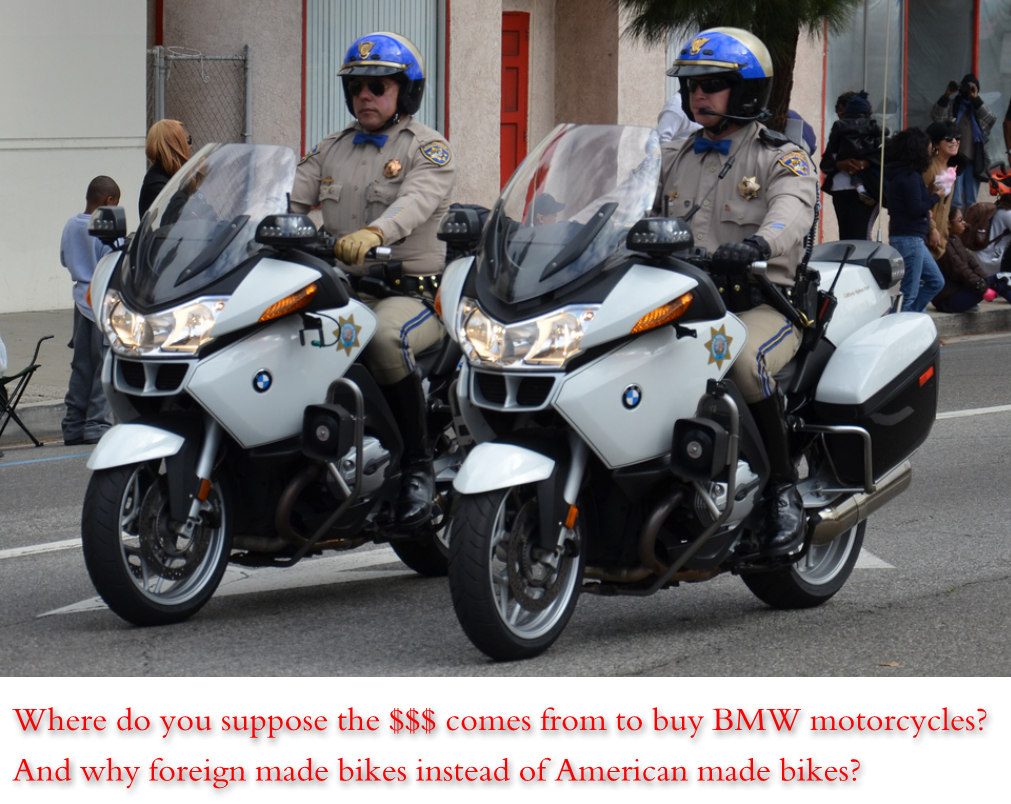

Know what else they enforce? State regulated commercial activity. Driving is commerce. They enforce commercial rules. The very rules in the Vehicle Code. Those rules apply to people who deliver people or stuff for a living like an UBER driver. Next time you see one of those cars check the plates. That device is being used for commercial purposes but it has a STANDARD GARDEN VARIETY EVERY DAY PLATE like what's on your ride. If what the UBER dude or dudette is doing with their car is legit with a STANDARD GARDEN VARIETY EVERY DAY PLATE then what's that tell you in spite of the fact there's both commercial and noncommercial plates and there's commercial and noncommercial driver license. The "non" variant must be "legal terms of art". Res ipsa loquitur. How can you come to any other conclusion based on ALL the government sources that's been provided on this page alone?

Don't know what "legal term of art" means? Billy Boy Clinton sure as hell does. He was once an attorney and Prezodunt. Member during the impeachment hearing and a question was posed to which he responded, "It depends on what the definition of is is.". I'll bet a lot-o-folks around the country didn't quite get the inside legal joke and thought he was bein a smart ass. Then there were those legal eagles who knew precisely what the former Adulterer In Chief said. LEGAL TERM OF ART.

LEGAL

TERM OF ART = BLACK

MEANS WHITE

I

would have to say that would be correct legal interpretation of the

law. Dealin with the laws of nature down in the sewer every day, I can say

we at the Sanitation Department know a little somethin about the law

alright!

The word "traffic" is defined in Webster's New International Dictionary as follows: "To pass goods and commodities from one person to another for an equivalent in goods or money; to buy or sell goods; to barter; trade." The subjects of manufacturing; producing; storing; selling, and handling any commodity are matters properly connected with the subject or traffic or trade in that commodity.

CALIFORNIA PENAL CODE

484d. As used in this section and Sections 484e to 484j, inclusive:

484d. As used in this section and Sections 484e to 484j, inclusive:

(9)

"Traffic"

means to transfer or otherwise dispose of property to

another, or to obtain control of property with intent to transfer or

dispose of it to another.

None of those definitions provide the term “congestion”, as in traffic means congestion. The term “traffic” is typically used instead of “congestion” to mean a mass of cars on the road at the same time in the same place slowing movement to a crawl. Unfortunately the use of the term “traffic” is completely incorrect but people act as if it’s not nor could be. So based on the foregoing Traffic Court adjudicates commercial grievances.

Let’s take another term that’s traditionally wrong when used, “driving”. No one has seen the legislative definition of that word because the Legislature has not defined it yet everyone knows without question what it means. It means, to the majority of people, going somewhere in a car while sitting behind the steering wheel. Unfortunately, like the term traffic, that’s an incorrect definition even though 99.9% of everyone believes that’s what it means. Driving, when considering all the circumstantial evidence provided by hundreds if not thousands of State and federal court cases where “commerce” or “business” is the central theme tying them all together. Driving is a job. Driving is an occupation. Driving is a profession. A driver is an employee. The term driver is a job description. And in order to qualify for the job of driver the applicant is required to have a valid driver license. That should tell the reader something. You will not be hired by Domino’s or Pizza Hut to deliver their pizzas unless you have a valid driver license. You will not be hired by FTD Florist to deliver their flowers unless you have a valid driver license. The driver license permits employment in the TRANSPORTATION BUSINESS as a driver. In California a cab driver has the same class license as the majority have in their wallets, Class C. One might argue that the Class C license stands for Class Commercial. The license is required to be hired as a driver at a cab company. There is no special business license other than the Class C required to be hired as a cab driver.

DRIVER.

One employed...

Bouvier’s Law Dictionary, 1856

DRIVER -- one employed in conducting a coach, carriage, wagon, or other vehicle..."

BOUVIER'S LAW DICTIONARY, (1914) p. 940.

DRIVER. One employed...

Black’s Law Dictionary, 4th Ed, 1951

Bouvier’s Law Dictionary, 1856

DRIVER -- one employed in conducting a coach, carriage, wagon, or other vehicle..."

BOUVIER'S LAW DICTIONARY, (1914) p. 940.

DRIVER. One employed...

Black’s Law Dictionary, 4th Ed, 1951

Did you go to the DMV to ask for permission to do something because you were told by adults you had to or you’d get into trouble? Did you know you were going to the DMV to ask for your government employee’s permission to work in the TRANSPORTATION BUSINESS? Remember, the DEPARTMENT OF MOTOR VEHICLES is a department within the CALIFORNIA STATE TRANSPORTATION AGENCY.

The CALIFORNIA STATE TRANSPORTATION AGENCY regulates TRANSPORTATION or the COMMERCIAL use of the streets and highways.

As was said by the supreme court of West Virginia (Dickey v. Davis, 76 W. Va. 576 [L. R. A. 1915F, 840, 85 S. E. 781]):

"The

right of a citizen to travel upon the highway and transport his

property thereon in the ordinary course of life and business differs

radically and obviously from that of one who makes the highway his

place of business and uses it for private gain, in the running of a

stage coach or omnibus. The former is the usual and

ordinary right of a citizen, a common right, a right common to all;

while the latter is special, unusual and

extraordinary. As

to the former, the extent of legislative power is that of

regulation; but as to the latter its power is broader; the

right

may be wholly denied, or it may be permitted to some and denied to

others, because of its extraordinary nature. This

distinction, elementary and fundamental in character, is recognized by

all the authorities."

The

argument is that the privilege of

using the public highways as a place for the transaction of private

business is not a vested right but a privilege which the state may

grant or withhold at its pleasure; that having the right to

withhold such privilege it may grant the same upon such terms and

conditions as it may see fit to impose; that it may say in

effect

to the applicant for such privilege, "I will grant you the privilege of

using the public highways for private gain in the transaction of your

business upon the condition that you in turn shall dedicate the

property used by you in such business to the public use of public

transportation." There is much force in this

contention. It has been repeatedly decided that the

right

of a common carrier to use the public highways for the conduct of his

business as such is not a vested or natural right, but is a mere

privilege or license which the legislature may grant or withhold in its

discretion, or which it may grant upon such conditions as it may see

fit to impose (Ex parte Lee, 28 Cal. App. 719 [153 Pac. 922]; Hadfield

v. Lundin, 98 Wash. 657 [Ann. Cas. 1918C, 942, L. R. A. 1918B, 909, 168

Pac. 516]; Le Blanc v. City of New Orleans, 138 La. 243 [70 South.

212]; Greene v. City of San Antonio (Tex. Civ. App.), 178 S. W. 6;

Gizzarelli v. Presbrey, 44 R. I. 333 [117 Atl. 359]; Morin v. Nunan, 91

N. J. L. 506 [103 Atl. 378]; Lutz v. City of New Orleans, 235 Fed. 978;

Cummins v. Jones, 79 Or. 276 [155 Pac. 171]; Packard v. Banton, 264

U.S. 140 [68 L. Ed. 596, 44 Sup. Ct. Rep. 264]; Memphis St. Ry. Co. v.

Rapid Transit Co., 133 Tenn. 99 [Ann. Cas. 1917C, 1045, L. R. A. 1916B,

1143, 179 S. W. 635]; Cutrona v. Mayor, etc. (Del.), 124 Atl. 658;

Taylor v. Smith, 140 Va. 217 [124 S. E. 259]; Schoenfeld v. Seattle,

265 Fed. 726; Ex parte Tindall, 102 Okl. 192 [229 Pac. 125]; Public

Service Com. v. Fox, 96 Misc. Rep. 283 [160 N. Y. Supp. 59]; Ex parte

Sullivan, 77 Tex. Cr. 72 [178 S. W. 537]; Child v. Bemus, 17 R. I. 230

[12 L. R. A. 57, 21 Atl. 539]; Ex parte Bogle, 78 Tex. Cr. 1 [179 S. W.

1193]; Fifth Ave. Coach Co. v. New York, 194 N. Y. 19 [16 Ann. Cas.

695, 21 L. R. A. (N. S.) 744, 86 N. E. 824]). The

supreme

court of Washington said in Hadfield v. Lundin, supra: "If

any